Let us begin by a quotation,

“Middle English” (in French) is the language which was spoken and written in Great Britain between 1150 and 1550 (...). These dates are only convenient mile stones: normally, there is no continuity solution for the evolution of a language. But if one compares the set of features caracterizing texts written during the “Middle English” period to those from the preceding period, one is struck by somes constant differences: a) vowels tend to get a standard tone (when they stil exist) e in (any) endings; b) a deep change and a great simplification of the inflection were determined by this levelling; c) as a consequence, there is a tendency (that has already begun in OE) to have recourse to analytic constructions or to prepositions instead of cases; d) finally, the lexicon has borrowed words from the French (consequences of the Norman conquest) or the Scandinavian languages (further to the Danelaw colonization) (note: ➳).

Compared to OE, the structure of the ME sentence is somewhat different, and tends to become the structure we know in CE. The main changes are:

Whereas in Old English, the order object-verb was very frequent, in particular in subordinate clauses and when the object was a pronoun, in Middle English this order became gradually less common, and ceased to show a correlation with clause type. (...) Another, probably related, Middle English change affected the position of particles relative to the verb. (...) such elements were also often preverbal in Old English. In the course of the Middle English period they gradually came to be restricted to postverbal position. In this case too, however, the older order continued to be used every now and then until the end of the Middle English period. (...) A further Middle English change involving verb position is the decline of the so-called `Verb-Second“ rule. (...) Verb-Second rapidly declined in the course of the last part of the fourteenth and in the fifteenth century, and saw a revival in the literary language in the sixteenth century ((21) ((21)): 82-3).

We can also quote Kroch & Taylor:

Pintzuk ((49), (50) and (51)) have shown that the transition from INFL- final to INFL-medial word order was a long-term trend characterizing the entire Old English period, so that its disappearance in Early Middle English can be taken as a continuation of Old English development rather than a break with it (...). [Early Middle English texts] exhibit all three of the base orders that have been proposed for Old English: INFL-final with an OV verb phrase, INFL-medial with an OV verb phrase, and the modern order – INFL-medial with a VO verb phrase ((38) ((38)):132-3).

These three base orders are the consequence of the different influences the ME dialects have been under. Still according to Kroch and Taylor,

Although we are not primarily concerned with the historical sociolinguistic dynamics that established the ME dialects, the sociolinguistic history of population contact and diffusion which underlie them is a matter of considerable interest (...). Specifically, we will see that the northern dialect of English most likely became a CP-V2 language under the extensive contact it had with medieval Scandinavian, contact that resulted from the Danish and Norwegian population influx into the North of England during the late OE period (...). The linguistic effect of this combination of population movement and population mixture was extensive ((39) ((39)) : 298-9).

Moreover,

The difference in the position to which the verb moves in different languages leads to subtle but clearly observable differences in the shape and distribution of verb second clauses. Most strikingly, while all V2 languages exhibit verb second order in main clauses, the two sub-types [IP-V2 and CP-V2] differ in the availability of this word order in subordinate clauses. The CP-V2 languages allow verb second order only in those embedded clauses that in some way have the structure of matrix clauses, either because the complementizer position is empty or because there is an additional complementizer position below the one that introduces the subordinate clause (the so-called `CP-recursion“). (...) The IP-V2 languages, on the other hand, show V2 order in a broad range of subordinate clauses. (...) We will further see that the southern dialect of ME preserves the V2 syntax of OE, despite having become, unlike OE, overwhelmingly I-medial and VO in basic order. In striking contrast to the southern dialect, however, the northern dialect of ME appears to have developed the verb-movement syntax of a standard CP-V2 language and hence to be similar in its syntax to the modern Mainland Scandinavian ((39) ((39)) : 297-8).

To sum up, we could say that the ME syntax still displays the OE syntactic order (V2 language), as well as the CE order, and that V2 rapidly declined from the end of the 14th century.

The members of this specific class of verbs are the same compared to OE, apart from one member. Like in Chapter 1, they all follow Mossé“s classification ((45) ((45))) (note: ➳)

Class 1 : WITEN “know”, OWEN (note: ➳) “own, have”.

Class 2 : DUGEN “be worth”.

Class 3 : CUNNEN “can, be able to”, ŠURFEN “need”, DURREN “dare”.

Class 4 : MON “ought” (only in the Northern dialect (note: ➳)), SCHULEN “should”.

Class 6 : MOTEN “can, should, have to“.

Non classified : MAGEN “be able to, can”.

Anomal verb: WILLEN “will, want”.

MON was not part of the class in OE, and is no part of it in Early Modern English nor in CE.

We shall mainly base our analysis on the following texts: the Ormulum (?c1200; East Midlands: south-west of Lincolnshire), Ancrene Riwle (1225-1230; West Midlands) and Chaucer“s The Canterbury Tales (1380-91; East Midlands: Londres) (note: ➳), as well as other texts from the ME corpus ((37) ((37))) if we require more specific examples.

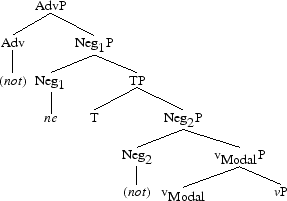

In the last chapter, we showed the existence of the functional heads C, T, Neg and v. Our analysis led us to add some more: a second Neg head, vModal for deontic preterite presents and Mood for epistemic preterite presents (which also hosts irrealis).

Similarly to OE, we also find the following structures: the ones where there is a lexical preterite present (i.e. followed by a direct object) and the ones where there is a semi-lexical preterite present (i.e. followed by an infinitive) base-generated under vModal).

| & | tohh | he | it | nowwhar | funde | žęr, | Ne | wollde | he | it | nęfre | cunnenn, | ... |

| & | although | he-SUJET | it-OBJET | nowhere | found-PRET | there, | NEG | voulut | il-SUJET | cela-OBJET | jamais | savoir, | ... |

and though he did not find it anywhere, he did not want to know, ... (CMORM, I,26.318)

| ant | alle | aʒen | hire | in | an | eauer | to | halden. |

| and | all-SUJET | should | her-OBJET | in | an | ever | TO | observe. |

and everyone should observe it always in the same way. (CMANCRIW,I.44.34)

| ... | ne | nenoteš | naut | his | wit | as | mon | ach | to | donne... |

| ... | NEG | knows-NEG+PRES | NOT | his | mind-OBJET | as | homme-SUJET | ought | TO | do... |

... he does not know his mind as a man should... (CMANCRIW,II.48.447)

| ʒef | ha | aʒen | tobeon | feor | from | alle | worldliche | men | hwet | hu | ancren | aʒen | to | hatien | ham | & | schunen, | ... |

| if | they-SUJET | ought | TO+be | far | from | all | wordly | men-PL. | what | how | cloistered-SUJET PL. | ought | TO | call | them-OBJET | & | teach, | ... |

if they have to get away from all the worldly men, this is how the cloistered men ought to call and teach them, ... (CMANCRIW,II.67.721)

| ... | ase | hwa | se | žus | seide, | Ich | nolde | forto | žolien | deaš | ... |

| ... | as | as | so | thus | said-PRET, | I-SUJET | NEG+would | FOR+TO | suffer | death-OBJET | ... |

as he then said, I did not want to suffer death... (CMANCRIW,II.76.889)

| deaš | me | ach | to | fleon | ase | forš | se | me | mei-PRES | ∅ | wiš | uten | sunne. |

| death-OBJET | one-SUJET | ought | TO | as | in | as | one-SUJET | may | ∅ | with | out | sun. |

you should flee from death as one may flee before the sun. (CMANCRIW,II.85.1029)

| & | tęrfore | hafe | icc | turrnedd | itt | Inntill | Ennglisshe | spęche, | Forr | žatt | I | wollde | bliželiʒ | Žatt | all | Ennglisshe | lede | Wižž | ęre | shollde | lisstenn | itt... |

| & | therefore | have-PRES | I-SUJET | translated-P.PASSE | it-OBJET | until | English | language, | for | that | I-SUJET | would-PRET | perfectly | that | all | English | people-SUJET | with | respect | should | listen | it-OBJET... |

and I have therefore translated it into English because I wanted all the English people to listen to it respectfully... (CMORM,DED.L113.33)

| Forži | ach | že | gode | habben | eauere | witnesse... |

| Therefore | ought | the | good-SUJET | have | ever | witness-OBJET... |

Therefore good should always have a witness... (CMANCRIW,II.56.543)

Like in OE, we find occurrences of preterite presents used lexicaly, i.e. followed by an object either direct or indirect. Yet, if we have a closer look all the different texts, we can notice that only a small number of these verbs are used this way.

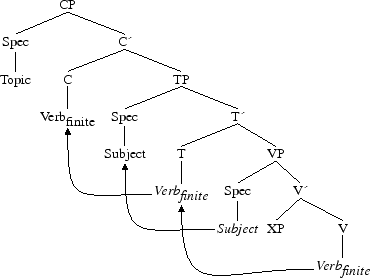

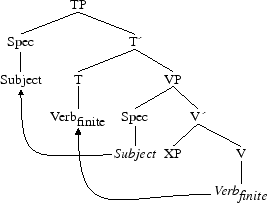

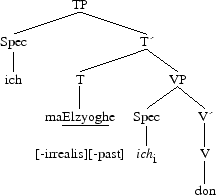

Let us recall the OE sentence when a preterite present is displayed. We shall only mention the main functional heads. SOV Sentences can be CP-V2 (direct questions, sentences introduced by a negative element or by the adverbs ža and žonne) as in Example (274) or IP(TP)-V2 as in Example (275)

Whenever no preterite present is displayed, the structures remain identical.

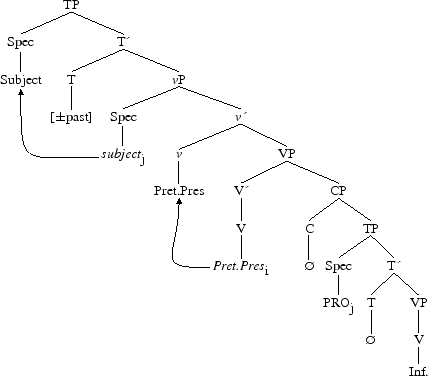

Before going any further in our analysis, let us go back to the structures of preterite presents in OE when they are lexical: Pret.Pres. + THAT-clause and Pret.Pres. + (FOR)TO-infinitive. In both cases, the complement of the preterite present is a CP.

When the complement is a CP-infinitive, it has a PRO subject controlling the subject of the sentence. The preterite presents are then control verbs which assign a θ-role to the subject (unlike raising verbs which do not have an external argument and do not assign external θ-role: they are one argument-verb) and to its object, the internal argument of V. The subject is case-marked nominative in all personal constructions, and mainly case-marked dative in impersonal ones.

Lexical preterite presents are base-generated under V, they assign a θ-role to the subject base-generated under Spec,vP. The first phase is over. The subject then raises to Spec,TP to satisfy the EPP features of T and the preterite present satisfy its tense feature under T. C then assigns nominative case under government to the subject, and Agree is done through T: the second phase is over and can be spelled out.

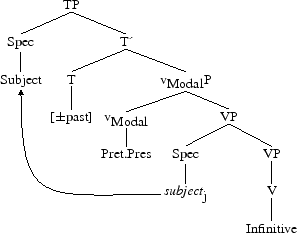

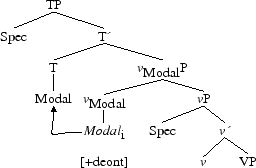

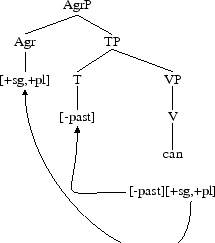

We have also underlined that these very verbs were semi-lexical when followed by an infinitive and they were also raising ones. Moreover, the grammatical subject of the preterite present is the semantic subject of V. They are not base-generated under V but under vModal, the functional head we introduced in the last chapter. We recall their syntactic structure:

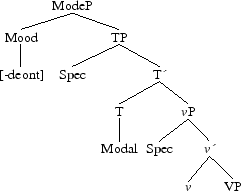

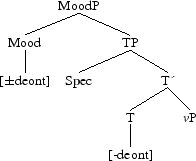

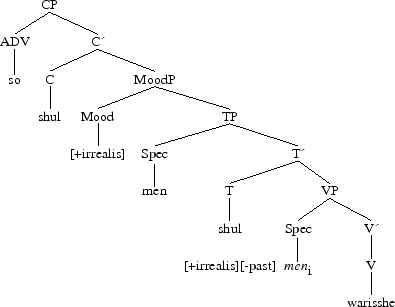

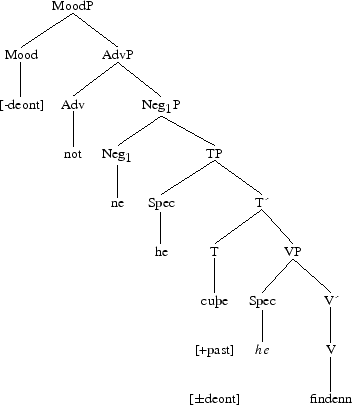

In late ME, we underlined that we could already talk about grammaticalisation (note: ➳) since we found examples taken from (19) ((19)) displaying epistemic-reading preterite presents. Moreover, we stressed the syntactic position Mood (above T within the domain of CP) corresponding to these preterite presents. Indeed, C is a periphrastic functional head which gives some more information about the sentence, about the relation established between a subject and its predicate. As far as epistemicity is concerned, it allows the speaker to voice an opinion reflecting his/her understanding or knowledge about this pre-established relation. So, Mood expresses the additional information brought by the speaker. Nevertheless, the epistemic preterite present is generated under T, and the phonological level, the [-deont] feature of Mood will “hop” to T, following the CE Affix Hopping (note: ➳). On a DM point of view, the morphemes of T and Mood merge, the two nodes remaining distinct.

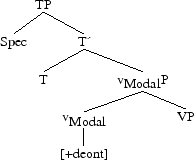

As for the deontic-reading preterite presents, they are generated lower than T, under vModal within the domain of vP. We then obtain the following structure in OE, and specially in ME:

CP - MoodP - TP - vModalP - (vP) - VP - (CP) - (TP) - (VP).

In ME, things change syntactically. The examples to come illustrate the major value change of the parameters: ME is now an SVO language. NP subjects and objects do not have morphological endings for person anymore; the features impoverish, triggering a change of value of the parameters, hence the structure becomes rigid. Yet, some structures remain V2. Then this syntactic competition (SOV-SVO sentences), the appearance of the dummy DO, the grammaticalisation and the epistemic readings of the preterite presents (note: ➳) are partially responsible for the setting of grammaticalisation. As a consequence, we shall name modal a preterite present which underwent grammaticalisation, i.e. a lexical or semi-lexical item becomes a grammatical, or functional, item.

The following examples show the ME SVO structure. As for questions or sentences beginning by a negative element (or focus), their structure is CP-V2 as we underlined in the previous chapter.

| Žeʒʒ | shulenn | lętenn | hęželiʒ | Off | unnkerr | swinnc | lef | brožerr. |

| They-SUJET | shall | let | honourably | off | their | labour | beloved | brother. |

Beloved brother, they shall let their labour go. (CMORM,DED.L53.21)

| Ža | seʒʒde | Zacariass | žuss | Till | Godess | enngell | sone; | Žurrh | whatt | maʒʒ | icc | nu | witenn | žiss | Žatt | itt | me | muʒhe | wurrženn? |

| Then | said | Zacharias | thus | till | God“s | angel | soon; | through | what | may | I-SUJET | now | know | this-OBJET | That | it-SUJET | me-OBJET | might | become? |

Then Zacharias said to God“s angel: “Alors Zacharie dit ą l“ange de Dieu : ” Through this, I can then know it, what might become of me?"` (CMORM,I,4.156)

| ʒiff | žu | willt | wurrženn | borrʒhenn, | Acc | nohht | onn | ane | wise | žohh, | Swa | summ | že | boc-SUJET | uss-OBJET | kižežž. |

| If | you-SUJET | will | be | born-P.PASSE, | But | NOT | on | one | way | then, | So | some | the | book | us | becomes known-PRES. |

If you want to be backed in a different way, as the book makes it known to us. (CMORM,I,172.1423)

| Heo | teacheš | al | hu | me | schal | beoren | him | wišuten, | ... |

| She-SUJET | teaches-PRES | all | how | one-SUJET INDEF | shall | bear | him-OBJET | out, | ... |

She teaches all about how to bring him forth, ... (CMANCRIW,I.42.17)

| ... | žet | ich | mote | blisfulliche | grete | že | in | heouene. |

| ... | that | I-SUJET | might | blissfully | greet | him-OBJET | in | heaven. |

... that I might greet him in heaven. (CMANCRIW,I.72. 277)

| ʒef | ani | seiš | wel | ošer | deš | wel, | ne | maʒen | ha | nan | loken | židerwart | wiš | richt | echʒe | Of | god | heorte. |

| if | any-SUJET | says-PRES | well | or | does-PRES | well, | NEG | may | he-SUJET | none | look | thither | with | right | eye | of | good | heart. |

if anyone says or does something good, he cannot look there with a rightful eye. (CMANCRIW,II.157.2133)

| ant | žu | schalt | finden | in | ham | gretunges | fiue. |

| and | you-SUJET | shall | find | in | him | greetings-OBJET PL | five. |

and you shall find five greetings in him. (CMANCRIW,I.74.290)

| Že | vres | of | že | Hali | Gast, | ʒef | ʒe | ham | wulleš | seggen, | seggeš | bifore | Vre | Lauedi | tiden. |

| The | hours-SUJET PL | of | the | holy | Spirit, | if | you-SUJET | them-OBJET | will | say, | say-IMP | before | our | Lady | time. |

If you want to say the hours of the Holy Spirit, say them before our Lady“s time. (CMANCRIW,I.74.297)

| And | with | this | swerd | shal | I | sleen | envie. |

| And | with | this | sword | shall | I-SUJET | kill | envy-OBJET. |

And I shall kill envy with this sword. (CMASTRO,662.C2.24)

| For | certes, | al | the | sorwe | that | a | man-SUJET | myghte | make | fro | the | bigynnyng | of | the | world... |

| For | certain, | all | the | sorrow | that | a | man-SUJET | might | make | from | the | beginning | of | the | world... |

For sure, all the sorrow that a man might cause from the beginning of the world... (CMCTPARS,291.C2.133)

| For | certes, | the | derke | light-SUJET | that | shal | come | out | of | the | fyr | that | evere | shal | brenne | shal | turne | hym | al | to | peyne | that | is | in | helle... |

| For | certain, | the | dark | light-SUJET | that | shal | come | out | of | tha | fire | that | ever | shall | burn | shall | transform | him-OBJET | all | to | pain | that | is-PRES | in | hell... |

For sure, the dark light that shall come out of the everburning fire shall transform him into all the pain that exists in hell... (CMCTPARS,291.C2.137)

| And | in | this | same | wise | maist | thow | knowe | by | night | the | altitude | of | the | mone | or | of | brighte | sterres. |

| And | in | this | same | way | may | you-SUJET | know | by | night | the | altitude-OBJET | of | the | moon | or | of | bright | stars-PL. |

By night, you can likewise know the altitude of the moon or the bright stars. (ID CMASTRO,669.C2.211)

| ... | for | thou | scholdest | knowe | that | the | mowynge | of | schrewes, | whiche | mowynge | the | semeth | to | ben | unworthy, | nis | no | mowynge; |

| ... | for | you-SUJET | should | know | that | the | ability-SUJET | of | tyrants-PL, | which | ability | you-OBJET | seems-PRES | TO | be | unworthy-OBJET, | NEG+is-PRES | no | ability-OBJET; |

... for you should know that the capacity of tyrants, which seems to be unworthy to you, is not one; (CMBOETH,448.C1.398)

If the examples have an epistemic reading, their syntactic structure is,

and if they have a deont reading, the structure is,

In a Section to come, we shall go back to these different structures to analyze them more accurately.

The word grammaticalisation can be defined as followed ((62) ((62)): 6):

The term grammaticalisation was first introduced by Meillet (1912) to describe the development of new grammatical (functional) material out of `autonomous“ words. [...] As Hopper and Traugott (1993: 1-2) point out, the term `grammaticalisation“ can be used to either describe the framework that considers “how new grammatical forms and constructions arise” or “the processes whereby items become more grammatical through time”.

Another definition would be (from (44) ((44))):

The process by which, in the history of a language, a unit with a lexical meaning changes into one with grammatical meaning(note: ➳).

Concerning modal verbs, the preterite presents, which were lexical and semi-lexical items, have become grammatical items, i.e functional words. This process of grammaticalisation can be seen through the syntax of the ME sentence, as a consequence of a morphological impoverishment (especially the loss of the irrealis endings) and the setting of new values to the existing parameters (such as the grammaticalisation of the preposition TO or the gradual appearance of the dummy DO) during that period. Nevertheless, this process took place gradually, as can be shown with the examples we are to analyze.

Until the ME period, preterite presents are semi-lexical verbs belonging to a specific class of verbs, hence behaving differently in syntactic terms. Whether epistemic or deontic, they are now raising verbs. Epistemic modals are base-generated under T and governed by MoodP; root modals are still base-generated under vModal and then raise to T, since they are grammatical, unlike lexical verbs.

In ME, they can still be used as lexical verbs (specially WILLEN, DURREN and CUNNEN), but the great majority of them tend to be followed by an infinitive which either has an epistemic or deontic reading.

This statement is very interesting: if there is an ambiguity between epistemic and root readings, it implies that these verbs indeed grammaticalize. (note: ➳)

We assume the ambiguous readings reflect the grammatical change of these verbs: from lexical items to grammatical items. The impoverishment of the verbal morphology, the rarer use of V2, a more rigid syntax and its relation to negation (which now does not precede the finite verb), and semantics (there are some shifting meanings for the preterite presents from the OE to the ME periods) are the reflection of the change of status of these verbs.

This grammaticalisation can also be seen morphologically: even if some forms still bear number and person, and specially 2nd person singular present or past, these verbs now only have a present and a past form. The present form is different from the form for lexical verbs since they possess the 3rd person singular in the present, as for the past form, there are no more differences between the irrealis endings.

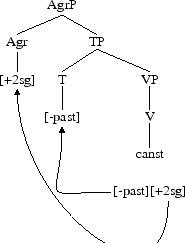

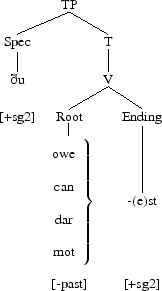

How can grammaticalisation be visible? Within the phase theory, the chosen items from the lexicon are already inflected and they satisfy a set of features with functional heads. Within (31) ((31))“s Distributed Morphology, each morpheme corresponds to one functional head whose uninterpretable features are identical to the morphemes“s. So, when there is impoverishment, some features of the morphemes disappear, reducing then the competition between lexical items. Let us take an example: in OE, we have canst, the present form (2nd person singular) of the preterite present CUNNAN. If we use a tree structure to represent it, we obtain:

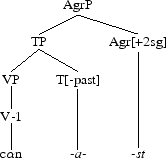

But we can also provide another morphological analysis of it. We can consider each morpheme on its own and say that a functional projection correponds to each of them. The structure we then get is not very different from the previous one. The main change is the status of the root <cαn> which is now one of the morpheme constituting the paradigm canst. The structure would be:

The V-1 notation is borrowed from (35) ((35)); it underlines that can is now a root, and it is the sum of all the morphemes which builds up the verb canst. This approach is different from Minimalism where the verb is chosen from the lexicon fully inflected. Yet this approach is not incompatible with it for it can reflect the grammaticalisation of the preterite presents in ME. Indeed, if these verbs are to be considered as paradigmas made of a root and a set of features, this phenomenom (i.e. grammaticalisation) leads to the loss of the endings and the vowel alternation (in the present indicative) of the preterite presents, that is, the morphosyntactic features of these lexical items are deleted. And it further leads to the deletion of some other features from other morphemes (what is called delinking in DM: when this delinking occurs, it entails the delinking of features which are dependent on them (the change is always from the more marked to the less marked value).

Let us take again the example žu canst and compare it with its contemporary equivalent you can (this form will be found in ME). We can note that the morphological mark of second person has disappeared and there is no longer vowel alternation (in OE, CUNNAN → can; in ME CUNNEN → can but CAN → can in CE).

We shall refer to this structure further on in our work, but correct it because after grammaticalisation modals are no longer semi-lexical but they are grammatical items.

Let us now go back to Examples (279) to (291), which allow us to underline the following important points for our analysis.

We have an SVO surface order, even if morphology is still visible on modals for the 2nd person singular and plural (Examples (285), (286) and (290)). Our hypothesis is that these morphological marks on modals (tense, person and number) and thou/ ʒe subjects (2nd person singular and plural) do not have any influence on the SVO structure.

We still find CP-V2 structures illustrating OE SOV structures. They can either be introduced by a negative element (Example (284)) or a topic (Examples (287), (290) and (291)).

In Examples (280) and (286) (but there are many others), we can question the strusture: is it SOV, hence OE, or SVO, for the object is found inbetween the subject and the finite verb, as we have considered so far that the object is the internal argumant of vP.

Finally, Examples (279), (282), (283), (288) and (289) display the ME SVO structures where cases are no longer morphologically visible (specially NOM and ACC, which freezes the structure), as person and number are on modal verbs.

With the coexistence of these two structures in ME, we also question the existence of the fuctional head reflecting this grammaticalisation. This point has been introduced in the previous chapter where we stessed the functional head vModal for semi-lexical preterite presents. This functional head still exists in ME, as Mood which has been introduced for epistemic modals and irrealis in OE. These two heads reflect two main types of modality in English: epistemic modality and deontic modality, even if according to (19) ((19)), epistemic readings of modals are less common than deontic readings. We could sum up this established fact saying that in the tree structure everything under T, that is vModal, is semi-grammaticalised and everything above T, that is Mood, is grammaticalised. T then marks the boundary between these two states, which means that the modal is or is not within the semantic scope of T. If it is not, the evaluation of the predicative relation is at the tense of the utterance; then it has an epistemic reading (belonging to the irrealis sphere) and the morphological past has no time value. But if tense scopes on the modal, it is deontic.

In the next sections, we shall analyze the preterite presents in relation to modality, underlining that both epistemic and deontic modals have the same syntactic structures, the only difference being that epistemic modals are base-generated under T and deontic modals under vModal. For deontic modals in particular, we shall draw a parallel with causative structures. We shall also sketch the analysis of the grammaticalisation of the preposition TO (followed by an infinitive) to relate it to the grammaticalisation of modal verbs. And we shall also go back to the notion of perfective aspect, as well as to the syntactic structure of causative verbs.

In the previous chapter, we saw that according to whether we were dealing with preterite present or lexical verbs, the infinitive structure was different. Is it the same in ME? Let us recall that OE infinitives have a particular ending -an, whatever the verb. In ME, we still find this ending -en, but a great number of infinitives are now bare for the morphological mark has disappeared. But this morphological loss(note: ➳) is also responsible for the grammaticalisation of preterite presents, among other things.

Concerning lexical verbs, we can note different types of structures:

The finite verb is followed by an inflected infinitive with TO,

| that | alle | schrewes | ne | ben | worthy | to | han | torment? |

| that | all | tyrants-SUJET | NEG | are-PRES | worthy | TO | have | torment-OBJET? |

that all tyrants are unworthy to be tormented? (CMBOETH,448. C2.421)

The finite verb is followed by an infinitive introduced by FORTO,

| ... | he | shall | cumenn | efft | To | demenn | alle | žede-OBJET, | & | forr | to | ʒeldenn | iwhillc | mann | Affterr | hiss | aʒhenn | dede. |

| ... | he-SUJET | shall | come | often | TO | judge | all-OBJET | country-OBJET, | & | FOR | TO | give back | each-OBJET | man-OBJET | after | his | own | death. |

... he shall often come to judge all the country and give each man back after his death. (CMORM,DED.L171.39)

| Prudence, | his | wyf, | (...) | bisoghte | hym | of | his | wepyng | for | to | stynte. |

| Prudence, | his | wife, | (...) | implored-PRET | him-OBJET | of | his | tears | FOR | TO | stop. |

His wife Prudence implored him crying to stop. (CMCTMELI,217.C1b.10)

the finite verb is followed by an infinitive without TO,

| Whan | Prudence | hadde | herd | hir | housbonde | avanten | hym | of | his | richesse | and | of | his | moneye, | ... |

| When | Prudence-SUJET | had-PRET | heard-P.PASSE | her-SUJET | husband-SUJET | boast | him-OBJET | of | his | wealth | and | of | his | money, | ... |

When Prudence had heard her husband boast about his wealth and money, ... (CMCTMELI,232.C2.601)

| ... | Ne | munnde | he | nęfre | letenn | himm | Žurrh | rodepine | cwellenn; |

| ... | NEG | remembered | he-SUJET | never | let | him-SUJET | through | the torment of the cross | kill; |

... He never remembered that he had let him be executed on the cross; (CMORM,I,68.612)

Finally, infinitive structures whose finite verb preceding them is let,

| žach | he | seo | žt | heo | him | mis paiʒe | he | let | hire | ʒete | iwurden. |

| although | he-SUJET | sees-PRES | that | she-SUJET | him-OBJET | dislikes | he-SUJET | lets-PRES | she-SUJET | yet | be. |

although he realizes he dislikes her, he lets her be as she is. (CMANCRIW,II.161.2223)

Let us now give examples of infinitive structures introduced by modals:

| But | nathelees, | men | shal | hope | that | every | tyme | that | man | falleth, | be | it | never | so | ofte, | that | he | may | arise | thurgh | Penitence... |

| But | nevertheless, | men-SUJET PL | shall | hope | that | every | time | that | one-SUJET | falls-PRES, | is-PRES | it-SUJET | never | so | often, | that | he-SUJET | may | arise | through | penitence... |

Nevertheless, men shall hope that whenever one falls (be it rarely), he can arise through penitence... (CMCTPARS,288.C2b.21)

| First | a | man | shal | remembre | hym | of | his | synnes; |

| First | a | man-SUJET | shall | remember | himself | of | his | sins-PL; |

A man must remember his sins; (CMCTPARS,290.C1.75)

| ... | whil | that | iren | is | hoot, | men | sholden | smyte... |

| ... | while | that | iron-SUJET | is-PRES | hot, | one-SUJET | should | smite... |

... one should strike while the iron is hot... (CMCTMELI,219.C1.82)

| And | therfore, | er | that | any | werre | bigynne, | men | moste | have | greet | conseil | and | greet | deliberacion. |

| And | therefore, | before | that | any | war-SUJET | begins-PRES, | one-SUJET | must | have | great | advise | and | great | deliberation. |

And therefore, before any war begins, a meeting should be held to deliberate. (CMCTMELI,219.C2.90)

| Forr | whase | mot | to | lęwedd | follc | Larspell | off | Goddspell | tellenn, | He | mot | wel | ekenn | maniʒ | word | Amang | Goddspelless | wordess. |

| For | whoever | must | to | simple | people | sermon-OBJET | of | Gospel | tell, | he-SUJET | must | well | develop | many | word-OBJET | among | Gospel | words-PL. |

For, whoever must say a sermon from the gospel to the ignorant people has to explain many words from it. (CMORM,DED.L53.16)

| Ža | Goddspelless | alle | žatt | icc | Her | o | žiss | boc | maʒʒ | findenn, | Hemm | alle | wile | icc | nemmnenn | her | Bi | žeʒʒre | firrste | wordess. |

| The | gospels-PL | all | that | I-SUJET | here | in | this | book | may | find, | them-OBJET | all | FUTUR | I-SUJET | name | here | by | their | first | words-PL. |

All the gospels I can find here in this book, I will name them using their first words. (CMORM,DED.L335.65)

| For | uh | an | schal | halde | žuttere... |

| For | each | one-SUJET | shall | hold | other... |

Because each one must hold the other... (CMANCRIW,I.44.26)

| & | heo | schal | habbe | leaue | to | gladien | hire | fere, | ... |

| & | she | shall | have | love | TO | rejoice | her | power, | ... |

& she shall have (enough) love to rejoice her power, ... (CMANCRIW,II.57.552)

| and | ye | shal | fynde | refresshynge | for | youre | soules. |

| and | you-SUJET | shall | find | refreshment-OBJET | for | your | souls-PL. |

and you shall find refreshment for your souls. (CMCTPARS,288.C1b.10)

The common change to all these verbs is that the infinitive can take en or be bare.

With AGEN, the infinitive structure is identical to that of lexical verbs for it is also introduced by TO, which reflects the grammaticalisation of this verb (note: ➳), and the parallel that can be drawn with the grammaticalisation of TO.

These different examples (modals and lexical verbs) are interesting from a morphological point of view since we have a “competition” between the two structures:

on the one hand, modal + INFINITIVE-en and verb + TO+ INFINITIVE-en, and

on the other hand, modal + INFINITIVE-∅ and verb + TO + INFINITIF-∅.

In Section 2.5.1, we analyzed the difference between the infinitive structure of modals and lexical verbs:

- [vModal Preterite present [vP subject Infinitive]] and,

- [VP VLexical[CP [C ∅ [TP PRO [T (TO) [VP Infinitive]]]]]] ou [VP VCausative [TP (TO) Infinitive]].

So, do these structure change when the infinitives become bare, i.e. uninflected? In other words, does this morphological loss have an influence on syntax, and more accurately on the preterite presents and TO?

In (62) ((62)): 112-9, the authors claim that the loss of the subjunctive and the inflection of infinitives plays an important role in the grammaticalisation of TO (the modal content of the subjunctive ending being transferred to TO), by supposing that mood features are now realized in a higher position, and not by the ending anymore. So, they consider the verbal forms of infinitive constructions introduced by TO as “subjunctives”: they are morphologically identical and, according to the authors, the increase of this kind of structure in ME is due to the decrease of subjunctive clauses displaying a marked morphology. Even if we do not follow their analysis of the TO particle, the morphological loss of the -en ending of infinitives and the -e/-en endings of the subjunctive is part of the grammaticalisation of some items such as the preterite presents or TO. As seen previously, the preterite presents and TO particle behave syntactically the same in relation to the ellipsis of the non finite verb. We can find this fact in ME.

| and | gief | he | hadde | werred | wiš | god | alse | že | deuel | him | to | ∅ | eggede... | |

| and | if | he-SUJET | had-PRET | fought-P.PASSE | with | god | also | the | devil-SUJET | him-OBJET | TO | ∅ | approached-P.PASSE | ... |

and if he had fought God, and that he had been appraoched by the devil ... (CMTRINIT,195.2699)

| to | speke | that | thou | woldist | not | ∅... |

| TO | speak | that | you-SUJET | would | NOT | ∅... |

say what you would not ... (CMAELR4,3.64)

Compared to what we have found in OE, causative verbs in ME do not have the same structure: they now have a VP complement like preterite presents and not a TP complement anymore. It would imply that these verbs do have a different syntactic position. In OE, we showed these verbs were lexical Vs; in ME, we assume they are semi-lexical verbs for their structure is identical to the CE one, that is operator verbs, and that they are vs. We voice the hypothesis they are now base-generated under v. The grammaticalisation of causative verbs would justify the grammaticalisation of deontic modals:

Let us give some examples.

| žu | habbe | heo | idon | mid | že | licome... |

| you-SUJET | have-PRES | them-OBJET | do | with | the | flesh... |

you have them do with flesh... (CMLAMBX1,21.242)

| uor | uirtue | makež | wynne | heuene, | and | onworži | že | wordle... |

| or | virtue-SUJET | makes-PRES | win | heaven, | and | be worth | the | world... |

or virtue makes us grant paradise and deserve the world... (CMAYENBI,84.

1630)

| (they | sholden) | at | the | last | maken | hem | lesen | hire | lordshipes... |

| (they | should) | at | the | last | make | them-SUJET | lose | their | powers-PL... |

at last, they should make them lose their powers... (CMCTMELI,231.C1.532)

Syntactically, it implies that they do not have the same position: they change from lexical to semi-lexical verb, whereas modals change from semi-lexical to grammatical verb, as shown in Example (314) (for deontic modals).

Thanks to these different examples (except the ones illustrating the causative verbs “have” and “make”), we have shown that modals and TO syntactically behave the same way with respect to the ellipsis of the non finite verb. Then, there exists a parallel between the evolution of the preterite presents and the evolution of TO. This is why Roberts and Roussou“s idea is attractive, and we can apply it to the preterite present verbs: with the loss of the infinitive and subjunctive endings, these verbs can undergo a grammatical change. They grammaticalise, and this can be seen through a great number of forms of should and would which belong to the irrealis sphere, i.e. conditional (note: ➳). But we shall deal with this later on in our work.

Contrary to OE, epistemic and deontic readings are easier to notice in ME because of the morphological impoverishment and semantic shifts of the preterite present verbs which trigger their grammaticalisation. The notions charaterizing them (possibility, necessity and obligation) are clearer. Moreover, some verbs like SCULEN and WILLEN are more and more used to express the future (which was already the case in OE but to a lesser extent), and the conditional.

Let us take some examples of deontic modals,

| ʒho | ža | shollde | ben | žurrh | Godd | Off | Haliʒ | Gast | wižž | childe. |

| you-SUJET | then | CONDITIONAL | be | through | God | of | Holy | Spirit | with | child. |

you should bear a child from the Holy Spirit. (CMORM,I,67.609)

| ʒe | ne | schulen, | ic | segge, | makie | na | ma | uuz | of | feste | biheastes. |

| you-SUJET | NEG | FUTURE, | I-SUJET | say-PRES, | make | no | more | use-OBJET | of | feast | promises-PL. |

I say that you will not use the promises of feast anymore. (CMANCRIW,I.46.53)

| ... | yet | thar | ye | nat | accomplice | thilke | ordinaunce | but | yow | like. |

| ... | yet | need | you-SUJET | NOT | accomplice | this | decree | unless | you-OBJET | like-PRES. |

... yet, you do not need to enforce this decree, unless you want it. (CMCTMELI,220.C2.127)

| Acc | žu | shallt | findenn | žatt | min | word, | ... |

| But | you-SUJET | FUTUR | find | that | my | word-SUJET, | ... |

But you shall find that my word, ... (CMORM,DED.L23.14)

[here the reading of SHALL is epistemic: I know that you will realize that...]

| ... | michte | for | te | serui | že, | wisdom | for | to | queme | že, | luue | ant | wil | to | don | hit; | mihte, | žet | ich | maʒe | don, | wisdom, | žet | ich | cunne | don, | luue, | žet | ich | wulle | don | al | žet | že | is | leouest. |

| ... | might | FOR | TO | serve | you-OBJET, | wisdom | FOR | TO | satisfy | you-OBJET, | love | and | will | TO | do | it-OBJET; | power, | that | I-SUJET | can | do, | wisdom, | that | I-SUJET | can | do, | love, | that | I-SUJET | will | do | all-OBJET | that | this-OBJET | is-PRES | beloved. |

... the might to serve you, the wisdom to satisfy you and the love and will to do it; the power I can use, the wisdom I can have, and love (which is everything) I want to give. (CMANCRIW,I.62.200)

| The | yeer | of | oure | Lord | 1391, | the | 12 | day | of | March | at | midday, | I | wolde | knowe | the | degre | of | the | sonne. |

| The | year | of | our | Lord | 1391, | the | 12 | day | of | March | at | midday, | I-SUJET | CONDITIONAL | know | the | degree | of | the | sun. |

In the year 1391 of our Lord, the twelfth day of March at midday, I woudl know the degree of the sun. (CMASTRO,669.C1.189)

| I | wolde | seye, | that | he | wolde | geten | hym | sovereyn | blisfulnesse; |

| I-SUJET | CONDITIONNEL | say, | that | he-SUJET | CONDITIONNEL | obtain | him-OBJET | soverein | blissfulness-OBJET; |

I would say that he would gain a soverein blissfulness; (CMBOETH,430.C1.82)

These examples allow us to show two things: 1) the process of grammaticalisation is set once and for all and 2) it is illustrated by the morphology of the modals which is to influence their meaning, that is past morphology but irrealis meaning (= conditional) (note: ➳).

Indeed, if we recall Structure (295) with the paradigm canst, we considered <cαn> to be its root which was in its turn not considered strictly speaking as a verb. From a semantic point of view, it does not imply the absence of meaning, since it means “know, be able”. But if we consider the root <cαn> as a V-1, we could be led to think it has less meaning than V but not that it has no meaning at all. Nevertheless, by becoming a V, and then a time element after grammaticalisation, the meaning is to stabilize (see (64) ((64)) for the change between OE an ME).

We shall add some more examples of epistemic modals also taken from (19) ((19)): 298-303. Examples (325) to (330) display a visible subject, Examples (331) to (339) do not.

sone hit męi ilimpen.

Soon it may happen. (a1225(?a1200) Lay.Brut 2250)

And if žou wynus it mai not be Behald že sune, and žou mai se.

And if you think it may not be behold the sun and you may see. (a1400(a1325) Cursor 289)

| Vr | neghburs | mai | žam | on | vs | wreke. |

| Our | neighbours | may | themselves | on | us | avenge. |

Our neighbours may avenge themselves on us. (a1400(a1325) Cursor 11963)

Sen žou ert both ong and fayre, žou mai haue childer to be žine aire.

since you are both young and fair you may have children to be your heir(s). (a1425(?a1350) 7 Sages(2) 2843)

žough že fflame of the ffyre of love may not breke out so žat it may be seyn, ... (1472 Stonor 123 I 126.36)

| Že | enbatelynge | aboute... | mai | well | be | her | feyned | holynesse | wherbi | žei | colouren | al | ere | euele. |

| The | battlements | around... | may | well | be | their | feigned | holiness | by means of which | they | disguise | all | their | evil. |

the battlements around ... may well be their feigned holiness by which they disguise all their evil. (?c1425(?c1400) Loll.Serm. 1.168)

| grisen | him | mahte | žet | sehe | hu... |

| feel horror | him-OBL | might | that | saw | how... |

He who saw how ... might feel horror. (c1225(?c1200) St.Juliana(Bod) 51.551)

| ne | schal | him | žurste | neuere. |

| NEG | shall | him-OBL | thirst | never. |

it shall never appease his thirst. (a1300 Žo ihu crist 85.24)

| Vs | shal | euer | smerte. |

| us-OBL | shall | always | feel pain. |

we shall always feel pain. (a1300 Sayings St.Bede(Jes-O) 83.336)

| hym | shall | not | gayne. |

| him | shall | NOT | gain. |

it will do him no good. (a1500(?a1300) Bevis(Cmb) p.83, textual note to 1583-1596)

| Ne | žurhte | že | neuer | rewe, | myhtestu | do | že | in | his | ylde. |

| NEG | needed | you-OBL | never | rue, | might you | put | tourself | in | his | protection. |

You would never need regret putting yourself in his protection. (a1300 A Mayde Cristes(Jes-O) 96)

| Mai | fall | sum | gast | awai | him | ledd, | And | es | vnto | že | felles | fledd. |

| may | fall | some | spirit | away | him | led, | and | is | into | the | hills | fled. |

Maybe some spirit led him away and he(?) has fled into the hills. (a1400(a1325) Cursor 17553)

| Hym | thar | not | nede | to | turnen | ofte. |

| him-OBL | need | NEG | necessarily | TO | turn | often. |

He need not necessarily turn often. (c1450(1369) Chaucer BD 256)

| Him | may | fulofte | mysbefalle. |

| him-OBL | may | very often | suffer misfortune. |

he may very often suffer misfortune. ((a1393) Gower CA 1.457)

| Hym | wolde | thynke | it | were | a | disparage | To | his | estate. |

| him-OBL | would | seem | it | was | a | disgrace | to | his | estate. |

It would seem to him a disgrace to his estate. ((c1395) Chaucer CT.C1. IV.908)

These examples underline the fact that epistemic readings increase at the ME period.

These examples also stress out the setting of the grammaticalisation of modals. This process has a very strong influence on syntax: as we have already said, the syntactic positions which are higher than T are grammaticalised, unlike the positions above T. Modals are still generated under vModal but before Vocabulary Insertion, vModal fuses with T. In the previous chapter, we underlined that Mood was “grammaticalised”; but, during the ME period vModal is to grammaticalise as well: deontic modals are grammatical items. And both epistemic and deontic modals are raising verbs.

Let us recall the structure of epistemic and deontic modals:

In Section 3.6.1, we stressed the existence of four functional heads Mod (according to Cinque: ModNecessity, ModPossibility, ModVolition and ModObligation. So there seems to exist functional heads for modals in ME whether they are epistemic or deontic. However, we shall not adopt Cinque“s multiplicity of functional heads, but two modal functional heads Mood and vModal. Both have the following features: [±deont], [±past], [±realis], but vModal will have a [+deont] feature and Mood a [-deont] one. The [±past] feature depends on the nature of the infinitive clause, that is whether it is a present or a past infinitive; the [±realis] is context-dependent. For each form, let us give a table where the italicized vowel represents the root and the bold morpheme the verbal (dental) inflection.

| Infinitive | [-past] [±irrealis] | [+past] [±irrealis] |

| MOTEN | mot | moste |

| OWEN | owe | ahte |

| WILLEN | wil | wolde |

| CUNNEN | can | cuže |

| DURREN | dar | dorste |

| MOWEN | mai | mighte |

| SCULEN | shal | sholde |

| ŠURFEN | žarf | žorfte |

| UNNEN | an | uže |

| WITEN | wot | wiste |

Let us take CUNNEN: with the form can, we know we have chosen a [-past] form (because of the root vowel <a>); with the form cuže, we know we have a past form thanks to the root vowel <u> and the dental suffix <že> indicating the [+past] tense. Both forms can be [±realis].

In the previous chapter, we defined two functional heads corresponding to each reading – epistemic or deontic – that could be made of the preterite present verbs.

According to the ME examples we have just analyzed in Section 3.6.2, the head vModal governs deontic modals and the Mood epistemic ones. As far as negation is concerned, we still find ne which no longer merges onto modals, and we more and more find not.

| & | žach | žurch | me | ne | schulde | hit | neauer | beon | iupped. |

| & | then | because | me | NEG | should | it-SUJET | never | be | open-P.PASSE. |

and then, becuase of me, it should never be opened. (CMANCRIW,II.70.795)

| Certes, | quod | she, | the | wordes | of | the | phisiciens | ne | sholde | nat | han | been | understonden | in | thys | wise. |

| Certainly, | said-PRET | she-SUJET, | the | words-SUJET PL | of | the | physicians-PL | NEG | should | NOT | have | been-P.PASSE | understood-P.PASSE | in | this | way. |

Certainly, she said, the words of the physicians do not have to be understood this way. (CMCTMELI,226.C2.360)

| And | therfore | seith | Salomon, | “The | wratthe | of | God | ne | wol | nat | spare | no | wight-OBJET...” |

| And | therefore | said-PRES | Salomon-SUJET, | “The | wrath | of | God-SUJET | NEG | will | NOT | spare | no | creature...” |

And Salomon then said: “The wrath od God will not spare any creature...” (CMCTPARS,291.C1.119)

| ne | a | more | worthy | thing | than | God | mai | not | ben | concluded. |

| nor | a | more | worthy | thing-SUJET | than | God | may | NOT | be | concluded-P.PASSE |

A more worthy thing than God cannot be concluded. (CMBOETH,433.C1.178)

| The | serpent | seyde | to | the | womman, | “Nay, | nay, | ye | shul | nat | dyen | of | deeth.” |

| The | serpent-SUJET | said-PRET | to | the | woman, | “No, | no, | you-SUJET | shall | NOT | die | of | death.” |

The serpent said to the woman: “No, no, you shall not die.” (CMCTPARS,296.C2b.

362)

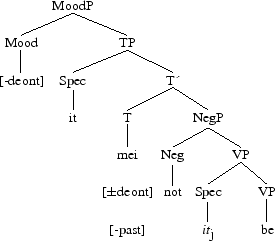

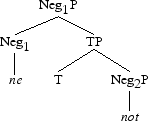

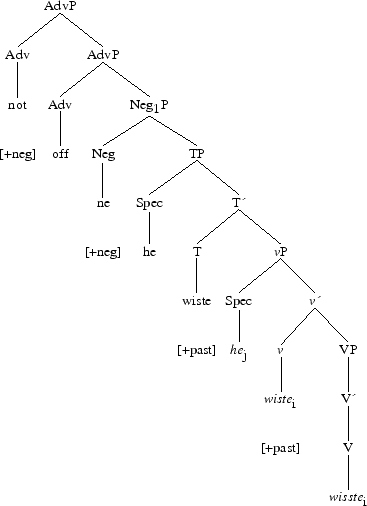

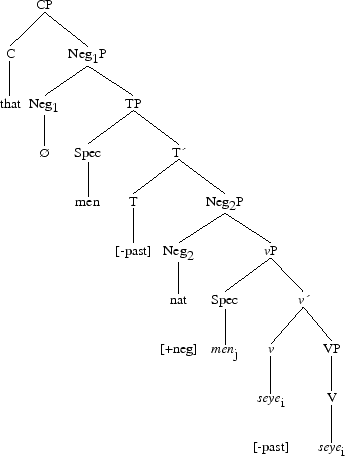

We are then confronted with two types of examples: examples where the main negation of the sentence is the negative adverbial particle ne, either used alone or conjointly with another negative element like not. In this case, ne is the head of Neg1P and not belongs to a second negative projection Neg2P which is lower in the structure (Neg1P-T-Neg2P) and where the head Neg is not realized but controlled by ne: negative concord then applies. Other examples display the structure where the main negation is not (note: ➳) which remains base-generated under Spec,Neg2P. As for Neg, it is not realized and controlled by ne anymore since it has disappeared. The grammaticalisation of modals and predominancy of not over ne then seem to be linked: in terms of Distributed Morphology, the head Neg2 is adjacent to T which merges with vModal. As a consequence, the linearization of the inserted lexical items is [T - NOT - vModal]; and yet, within the ME corpus, the main negation not does not precede the finite verb, whatever the type of verb.

It implies an impoverishment of some sort: with the disappearence of the functional node Neg1, there is the delinking of the second functional node; as it is positioned in between T and V, V can no longer be c-commanded by the T morpheme since there is no more adjacency of V and T: Fusion cannot be done, hence the disappearance of V2 sentences with lexical verbs.

During the ME period, we have underlined that two functional heads for modals coexist. Examples from the corpus have allowed us to note the [+neg] feature to be weaker since the cliticization of ne could also happen on lexical verbs (and not only modal verbs): we have found examples in all texts (except in Chaucer) and cliticization always happens when the verb begins by a vowel. This feature is also less strong because not tends to replace the negative adverbial particle ne which immediately preceded the finite verb (we refer the reader to Section 3.7).

| ne | Preche | ʒe | to | nan | mon | ne | naske | ʒe | of | counseil. |

| NEG | preach-IMP | you-SUJET | to | no | man | nor | NEG+ask-IMP | you-SUJET | of | advice. |

do not preach to any man nor ask for advice. (CMANCRIW,II.58.569)

| ... | Žatt | tu | ʒet | nunnderrstanndesst | nohht, | Forr | žatt | tu | narrt | nohht | fullhtnedd, |

| ... | that | you-SUJET | yet | NEG+understand-PRES | NOT, | for | that | you-SUJET | NEG+is-PRES | NOT | encouraged-P.PASSE... |

... the one that you do not understand yet because you are not encouraged... (CMORM,II, 241.2494)

Let us take some examples of epistemic and deontic modals again and analyze them.

Examples (349) and (350) are epistemic, Examples (351) and (352) are deontic.

| And | if | žou | wynus | it | mai | not | be | Behald | že | sune, | and | žou | mai | se. |

| et | si | tu | penses | cela | peut | NOT | źtre | Regarde | le | soleil, | et | tu | pourras | voir. |

And if you think it may not be behold the sun, and you may see. (a1400(a1325) Cursor 289)

| Vr | neghburs | mai | žam | on | vs | wreke. |

| Our | neighbours | may | themselves | on | us | avenge. |

Our neighbours may avenge themselves on us. (a1400(a1325) Cursor 11963)

| Acc | žu | shallt | findenn | žatt | min | word, | Eʒʒwhęr | žęr | itt | iss | ekedd, | ... |

| But | you-SUJET | shall | find | that | my | word-SUJET, | everywhere | there | it-SUJET | is-PRES | developed-P.PASSE, | ... |

But you shall find that my word, wherever it is developed, ... (CMORM, DED.L23.14)

| And | for | he | shal | be | verray | penitent, | he | shal | first | biwaylen | The | synnes | that | he | hath | doon... |

| And | for | he-SUJET | shall | be | very | penitent-OBJET, | he-SUJET | shall | first | wash | the | sins-OBJET PL | that | he-SUJET | has-PRES | done... |

And because he must be penitent, he shall wash his sins away... (CMCTPARS,288.C2b.17)

Let us first focus on the structure of infinitive clauses when the modal is epistemic with Example (349):

The semantic subject of be raises to Spec,TP to become the grammatical subject of mei, which has an epistemic reading. The modal is base-generated under T and satisfies its [-deont] feature with Mood within the domain of CP. On a semantic ground, this does not question the subject-predicate relation, it only questions the truth/falsehood of this relation.

Before giving the structure of deontic modals again, let us give some more examples which will help us to demonstrate that they are indeed raising verbs. In these examples, the object between square brackets.

| and | yf | they | knewen | that | thei | shuld | [no | thinge] | resceyue... |

| and | if | they-SUJET | knew-PRET | that | they-SUJET | should | no | thing-OBJET | receive... |

and they knew they should not receive anythinge... (CMAELR4,3.49)

| for | eauer | me | schal | [že cheorl] | polkin | & | pilien. |

| fro | ever | one-SUJET | shall | the slave-OBJET | rob | & | plunder. |

because the slave shall always be robbed and plundered. (CMANCRIW,II.69.773)

| Žis | zenne | him | to-delž | and | spret | ine | zuo | uele | deles | žet | onneaže, | me | may | [hise] | telle. |

| This | sin-SUJET | him-OBJET | distributes-PRES | and | spreads-PRES | in | so | well | parts-PL | that | with difficulty, | one-SUJET | may | theirs-OBJET | tell. |

This sin distributes and spreads him so that it is difficult to recognize theirs. (CMAYENBI,17.251)

| ʒif | žei | wolde | not | be | chastised, | žei | schulde | [his | loue] | lese | for | euermore. | |

| if | they | would | NOT | be | chatised-P.PASSE, | they-SUJET | they | should | his | love | lost | for | ever more. |

if they had not been chastised, they should not have lost his love for ever. (CMBRUT3,3.40)

| for | they | ne | kan | [no | conseil] | hyde. |

| for | they-SUJET | NEG | can | no | secret-OBJET | hide. |

because they cannot hide any secret. (CMCTMELI,224.C1.281)

| ... | žat | he | louež | or | scholde | [him] | seruen. |

| ... | that | he-SUJET | loves | or | should | him | serve. |

... that he loves or should serve him (CMEDVERN,248.363)

| žt | me | schulde | [katerine] | bringe | biuoren | him. |

| that | one-SUJET | should | Catherine-OBJET | bring | before | him. |

that Catherine should be brought before him. (CMKATHE,35.260)

These examples show that all these objects are semantically bound to the finite verbs, which proves that deontic modals are raising verbs like epistemic ones.

We do not really know whether the grammaticalisation of modal verbs and TO) took place before or after the loss of verbal morphology in ME, or whether this loss triggers the grammaticalisation of modals and TO. Yet, let us recall that CE still has the subjunctive mood, even if it has become rarer. Moreover, we have underlined that the loss of the -en morpheme both for infinitives and subjunctives has triggered the grammaticalisation of the particle TO (and preterite present verbs) which could play the role of modal head, that is “mood”, for the subjunctive, according to (62) ((62))“s analysis. So, some modals like SCULEN and WILLEN can have a past form but a conditional value, placing them within the irrealis sphere (note: ➳). Then, if a dissociation exists between morphological tense and syntactic tense, there is grammaticalisation of these very forms, where the morphological form becomes a modal form. Let us check if these examples confirm this statement.

| “Though | I | wiste | that | neither | God | ne | man | ne | sholde | nevere | knowe | it, | yet | wolde | I | have | desdayn | for | to | do | synne.” |

| “Though | I-SUJET | know-PRES | that | neither | God | nor | man | NEG | should | never | know | it-OBJET, | yet | would | I-SUJET | have | disdain-OBJET | FOR | TO | do | sin-OBJET.” |

“Although I know that neither God nor man should ever know it, Bien que je sache que ni Dieu ni l“homme ne devra jamais le savoir, however, I would never despise to sin.” (CMCTPARS,290.C2.94)

[“Although” takes roots in the irrealis, so sholde and wolde both belong to the irrealis sphere, their morphological forms are no longer a past one.]

| And | for | as | muche | as | a | man | may | acquiten | hymself | biforn | God | by | penitence | in | this | world, | and | nat | by | tresor, | therfore | sholde | he | preye | to | God | to | yeve | hym | respit | a | while | to | biwepe | and | biwaillen | his | trespas. |

| And | for | as | much | as | a-SUJET | man-SUJET | may | fulfill | himself-OBJET | before | God | by | penitence | in | this | world, | and | NEG | by | treasure, | therefore | should | he-SUJET | pray | to | God | TO | give | him-OBJET | respite-OBJET | a | while | TO | regret | and | wail | his | death-OBJET. |

And for as much as a man may fulfill before God through penitence, not treasure, he should therefore pray him to give him a moment of respite te regret and cry over his death. (CMCTPARS,291.C2.132)

[same thing as the preceding example, “for as much as” fixes the utterance into the irrealis.]

| but, | certes, | he | sholde | suffren | it | in | pacience | as | wel | as | he | abideth | the | deeth | of | his | owene | propre | persone. |

| but, | certainly, | he-SUJET | should | suffer | it-OBJET | in | patience | as | well | as | he-SUJET | waits-PRES | the | death-OBJET | of | his | own | propre | person. |

but it is certain that he should have to suffer it patiently, as he awaits his own death. (CMCTMELI,217.C1b.20)

[the time of the utterance is the present, but sholde does not have a past value; it has a prospective value, as the death to come, it is a “future” tense.]

| The | yeer | of | oure | Lord | 1391, | the | 12 | day | of | March | at | midday, | I | wolde | knowe | the | degre | of | the | sonne. |

| The | year | of | our | Lord | 1391, | the | 12 | day | of | March | at | midday, | I-SUJET | would | know | the | degree-OBJET | of | the | sun. |

In the year 1391 of our Lord, the twelfth day of March at midday, I woudl know the degree of the sun. (CMASTRO,669.C1.189)

[wolde has a conditional meaning (which implies here: if all the conditions are fulfilled, that very day, I will know it).]

| Žu | žohhtesst | tatt | itt | mihhte | wel | Till | mikell | frame | turrnenn, | ʒiff | Ennglissh | follc, | forr | lufe | off | Crist, | Itt | wollde | ʒerne | lernenn | & | follʒhenn | itt... |

| You-SUJET | thought-PRET | that | it-SUJET | might | well | till | great | from | translate, | if | English | people-SUJET, | for | love | of | Christ, | it-OBJET | would | willingly | learn | & | follow | it-OBJET... |

You thought that it could be wholly translated if the English people had willingly learnt and followed it fro the love of Christ... (CMORM,DED.1.5)

[for this example, the form mihhte belongs to the past, but we can question wollde, because it is introduced by “if” which expresses a condition.]

| ... | Forr | žatt | he | wollde | uss | waterrkinn | Till | ure | fulluhht | hallʒhenn, | Žurrh | žatt | he | wollde | ben | himm | sellf | Onn | erže | i | waterr | fullhtnedd. |

| ... | For | that | he-SUJET | would | us-OBJET | water-follower | till | our | baptism | consacrate, | because | that | he-SUJET | would | be | him-OBJET | self | on | earth | in | water | baptised-P.PASSE. |

... so that he would consacrate us at our christening because he would himself be christened on earth and in water. (CMORM,DED.L171.44)

[in this example, “for” roots the utterance in the irrealis sphere, the two of forms of wollde are only morphological past forms.]

| ... | hit | walde | to | swiše | hurten | ower | heorte | ant | maken | ou | swa | offered | žet | ʒe | muhten | sone, | as | God | forbeode, | fallen | i | desesperance, | ... |

| ... | it-SUJET | would | too | much | hurt | your | heart-OBJET | and | make | you-SUJET | so | offered-P.PASSE | that | you-SUJET | might | soon, | as | God-SUJET | forbidden-PRET, | fall | in | despair, | ... |

... it would hurt your heart too much and expose yourself, as a consequence you might become desesperate... (CMANCRIW,I.46.65)

[the forms walde and muhten both belong to the irrealis.]

| “hwerof | chalengest | žu | me, | že | appel | žt | ich | loki | on | is | for bode | me | to | eoten, | naut | to | bi halden”, | žus | walde | eve | inoche | raše | habben | i onswered. |

| “whereof | defies-PRES | you-SUJET | me-OBJET, | the | apple-SUJET | that | I-SUJET | look-PRES | on | is-PRES | forbidden-P.PASSE | me-OBJET | TO | eat, | NOT | TO | contemplate”, | thus | would | Eve-SUJET | enough | quick | have | answered-P.PASSE. |

“What are you challenging me of, the apple I am looking at, I am forbidden to eat it but no to look at it”, it is how Eve would have quickly liked to answer. (CMANCRIW,II.44.405)

[walde has a conditional meaning according to the context; moreover, it is the complex structure MD + HAVE + V + EN, where walde functions as a modal, but the tense of the sentence is expressed through HAVE + EN, as in contemporary English.]

| forži | wes | ihaten | on | godes | laʒe | žt | put | were | iwriʒen | eauer. | & | ʒef | ani | were | vnwriʒen | & | beast | feolle | žer | in | he | hit | schulde | ʒelden. |

| because | was-PRET | called-P.PASSE | on | god“s | law | that | holes-SUJET | were-PRET | hidden-P.PASSE | ever | & | if | any | was-PRET | no hidden-P.PASSE | & | beast-SUJET | fell-PRET | therein | he-SUJET | it-OBJET | should | give back. |

because God“s law said that the holes were still hidden, and if none of them were found and a beast fell in one of them, it had to be given back. (CMANCRIW,II.47.440)

[here again, “if” roots the utterance displaying schulde in the irrealis sphere, giving a conditional meaning to it.]

According to the texts, the two structures for modal verbs coexist whereas the morphological marks for the subjunctive do not appear anymore, since they merge with the morphological marks for the present. Then the context will help us know if we are dealing with Mood [+irrealis] or not.

Like in OE, ME has two tenses: present ([-past]) and past ([+past]). Once again, morphology will tell us the tense of the finite verb. But unlike OE, morphology is less marked since we can only find the 2nd person singular and plural inflections (present and past) and sometimes the plural inflection. There is no vowel alternation anymore for modal verbs between the infinitive and the present form, the only vowel alternation remaining is between the present and past form. Yet, as Examples (361) to (369) have shown, a past form does not necessarily have a past value.

The following examples illustrate the present forms of (shall, mei and moot) and the past forms of (walde/wollde, mihhte, cuže/koude, shollde and must).

| For | uh | an | schal | halde | žuttere | efter | žet | heo | best | mei | wiš | hire | seruin | žeo | inre. |

| For | each | one-SUJET | shall | support | the whole | to get | that | they | best | may | with | their | accomplish | this | inside. |

Because each of them must support the others so that they can inwardly accomplish this. (CMANCRIW,I.44.26)

| “Thanne | moot | it | nedis | be | that | verray | blisfulnesse | is | set | in | sovereyn | God.” |

| “Then | must | it-SUJET | necessarily | be | that | very | blissfulness-SUJET | is-PRES | set-P.PASSIF | in | sovereign | God.” |

“The the real blissfulness must necessarily set into the sovereign God.” (CMBOETH,432.C1.148)

| he | cuže | ben | Himm | ane | bi | himm | sellfenn. |

| he-SUJET | could | be | him-OBJET | one | by | him | self. |

he could finally be on his own. (CMORM,I,26.314)

| By | thise | resons | that | I | have | seid | unto | yow, | and | by | manye | othere | resons | that | I | koude | seye, | I | graunte | yow | that | richesses | been | goode | to | hem... |

| By | these | reasons-PL | that | I-SUJET | have-PRES | said-P.PASSE | unto | you, | and | by | many | other | reasons-PL | that | I-SUJET | could | say, | I-SUJET | promise-PRES | you-OBJET | that | riches-PL | are-PRES | good | to | them... |

For all the reasons I said to you, and for many more that I could add, I promise you that the riches are good for them... (CMCTMELI,233.C1.623)

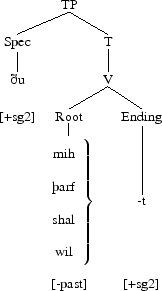

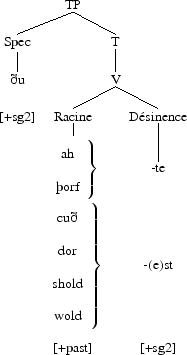

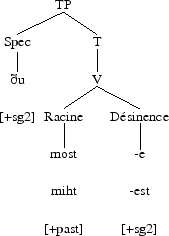

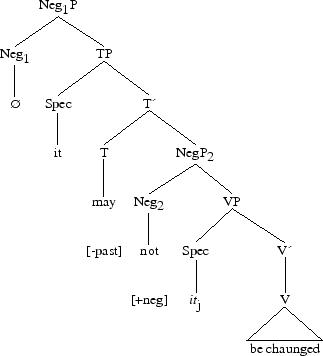

These examples allow us to notice two things: first, there is a morphological standardization of past forms of SHALL, WILL and CAN; secondly, MUST still has two morphological forms, but only the past one will remain in CE (with a present meaning). So, we have the following syntactic structures for the second person of the present and past:

If we compare the verbal forms of structures (374) and (374.b), we can notice that there is a vowel alternation between the present and past forms of OWEN, CUNNEN, ŠURVEN, SCULEN and WILLEN. But it is no longer the case for MOTEN et MOWE. Their only other morphological mark is the present and past plural endings, which is identical for all the persons: -en, but this ending is not always identified. Moreover, this mark, as well as the infinitive and subjunctive ones are also identical, as a consequence, they disappear. But, still, we can question whether a past morphological form is a past tense. When we deal with the perfective aspect, we shall see that we can partly answer this question. However, the choice between past and conditional will always be context-dependent.

Now, what about the functional head Mood which has been introduced in the last chapter?

As we have mentioned it, the indicative and subjunctive morphological endings become identical, and for the preterite presents, we have three types of verbs: preterite presents whose ending is identical for both present indicative and subjunctive, preterite presents which do not have a subjunctive form and verbs whose present indicative and subjunctive are different. In all these cases, past subjunctive does no longer exist (see Appendix A for more details). In the following table, the root vowel is italicized and the ending in bold.

| Verbe | -irréel sg-pl | +irréel sg-pl | |

| Formes identiques | OWEN | owe/ owe(n) | owe/(owen) |

| DURREN | dar/– | dar/– | |

| MOTEN | mote/mote(n) | mote/moten | |

| Pas de subjonctif | DUGEN | dowe/dowen | – |

| Formes différentes | UNNEN | an/– | unnen/– |

| CUNNEN | can/cunnen | cunne/cunnen | |

| ŠURFEN | žarf/žurfon | žurve/žurven | |

| SCULEN | shal/shulen | shule/shulen | |

| MOWE | mei/mugen | mowe/mowen | |

| WILLEN | wil/wilen | wille/willen |

This table highlights two things: in ME, a functional head Mood exists, which is only realized in the singular by now (for verbs having distinct forms). For the other verbs, it will depend on the context to know whether it is an indicative or a subjunctive form. But, above all, it means that as the subjunctive mood disappears morphologically, the position Mood is left empty for epistemis modals. Let us take some examples.

| ... | mihte, | žet | ich | maʒe | don, | wisdom, | žet | ich | cunne | don, | luue, | žet | ich | wulle | don | al | žet | že | is | leouest. | ||||||||||||||||

| ... | might | FOR | TO | serve | you-OBJET, | wisdom | FOR | TO | satisfy | you-OBJET, | love | and | will | TO | do | it-OBJET; | power, | that | I-SUJET | can | do, | wisdom, | that | I-SUJET | can | do, | love, | that | I-SUJET | will | do | all-OBJET | that | this-OBJET | is-PRES | beloved. |

... the might to serve you, the wisdom to satisfy you and the love and will to do it; the power I can use, the wisdom I can have, and love (which is everything) I want to give. (CMANCRIW,I.62.200)

| ... | Butt | iff | itt | shule | tacnenn, | Whatt | weorrc | himm | is | žurrh | Drihhtin | sett | To | forženn | her | onn | eorže. |

| ... | But | if | it-SUJET | shall | mean, | what | work | him-OBJET | is-PRES | through | Lord | set-P.PASSE | TO | accomplish | here | on | earth. |

except that he has to say what work is set by God so that he can accomplish iti on earth. (CMORM,I,61.559)

| ant | alle | aʒen | hire | in | an | eauer | to | halden. |

| and | all-SUJET | ought | them-OBJET | in | an | ever | TO | hold. |

and that all should always hold it. (CMANCRIW,I.44.34)

| ne | ne | žurue | naut, | ne | ne | ahʒe | naut | halden | on | ane | wise | že | vtterre | riwle... |

| nor | NEG | need | NOT, | nor | NEG | ought | NOT | hold | in | one | way | the | whole | rule-OBJET... |

neither need it nor should it hold the whole rule in any way... (CMANCRIW,I.44.36)

| but | that | schal | he | nat | fynde | in | tho | thynges | that | I | have | schewed | that | ne | mowen | nat | yeven | that | thei | byheeten? |

| but | that-OBJET | shall | he-SUJET | NOT | find | in | the | things-PL | that | I-SUJET | have-PRES | showed-P.PASSE | that | NEG | might | NOT | give | that | they | promise? |

but does he have to find that in the things I have showed him that he cannot give what they are promising? (CMBOETH,430.C1.83)

| that | right | as | maladies | been | cured | by | hir | contraries, | right | so | shul | men | warisshe | werre | by | vengeaunce. |

| that | right | as | illnesses-SUJET PL | was-PRET | healed-P.PASSE | by | their | opposites-PL, | right | so | should | one | cure | war | by | vengeance. |

as all illnesses are cured by their opposites, one should likewise cure war by vengeance. (CMCTMELI,218.C2.62)

Example (376) illustrates the [-irrealis] mood, as for Examples (377) to (381), they illustrate the [+rrealis] mood. Let us now give the structures of (376) (now numbered (382)) and (381) (now numbered (383)) to exemplify our analysis.

The preceding examples underline that the [-irrealis] and [+irrealis] features of the functional head Mood are present in ME, regardless of the morphological marks. In (46) ((46)), the author underlines the fact that the “modal” past firmly sets at that period. Then, even if the subjunctive ending is lacking, the [+irrealis] feature of the Mood head exists, as Examples (361) to (369) have exemplified. And this fact still continues in CE.

General term for verbal categories that distinguish the status of events, etc. in relation to specific periods of time, as opposed to their simple location in the present, past, or future. (...) I have read the paper means that, at the moment of speaking, the reading has been completed: it is therefore present in tense but perfect in aspect. ((44) ((44)))

By the end of the OE period, corresponding to the appearance of the epistemic preterite presents, we noticed the less common use of aspect in the corpora ((52) ((52)) and (67) ((67))) motivating then the presence of the functional head Mood for epistemic modals and aspect. However, in the very late OE period (around the XIIth c.), aspect appears again, but syntactically lower in the structure.

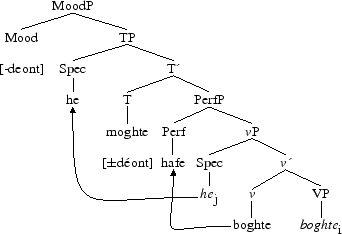

This fact continues on in ME, and we have found many examples of structures displaying MD + HAVE + EN (the modals are either epistemic or deontic), where the perfective aspect reflects a temporal landmark, as is the case in CE.

| He | moghte | hafe | boghte | vs | agayne | on | ožer | manere. |

| he-SUJET | might | have | bought | us-OBJET | again | on | other | manner. |

He might have bought it from us somehow or other. (CMEDTHOR,43.631)

| ženne | we | mihten | more | han | loued | vre | buggere | žen | vre | makere; |

| then | we-SUJET | might | more | have | loved | our | buyer | than | our | maker; |

then we might have loved more our buyer that oiur maker; (CMEDVERN,256.691)

| sche | cowd | or | ellys | mygth | a | schewyd | as | sche | felt. |

| she-SUJET | could | or | else | might | have | showed | as | she-SUJET | felt-PRET. |

she could, or at least might, have showed what she felt. (CMKEMPE,39.871)

| he | wolde | sone | a | revenged | us. |

| he-SUJET | would | soon | have | revenged | us-OBJET. |

he would have soon revenged us. (CMMALORY,32.1005)

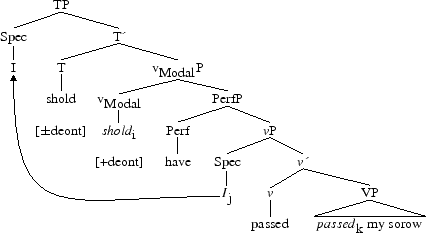

| for | haddest | thow | not | shewed | me | that | syght | I | shold | have | passed | my | sorow. |

| for | had-PRET | you-SUJET | NOT | showed | me-OBJET2 | that | sight-OBJET1 | I | should | have | surpassed | my | sorrow-OBJET. |

because if you had not showed me this sight, I should have surpassed my sorrow. (CMMALORY,66.2249)

Here are some examples of structures for epistemic ((384)) and deontic ((388)) modals.

These two examples demonstrate that Aspect is now to be found under a specific functional head which is different from the head Mood, but we shall not go into detail for now.

During the ME period, not prevails over ne even if ne does not disappear totally in early ME. The predominance of not allows us to underline the scope of the negation when it concerns epistemic or deontic modals.

In the last chapter, we underlined the two phenomena of negative concord (when there are two negative elements within a single sentence, they do not cancel each other out but they express a single negation) and Neg criterion (every negative head must be in a head-head relation with a negative operator within its minimal research domain). But in ME, can we still talk about these two processes? The following examples illustrate that point: as in OE, there is still negative concord when the principal negation of the sentence remains the negative adverbial particle ne; but when the principal negation becomes not, the process of negative concord tends to disappear but Neg criterion does not, since the relation with a covert negative operator takes place whenever not is the only negation of the sentence.

| Ne | munnde | he | nęfre | letenn | himm | Žurrh | rodepine | cwellenn; | |

| ... | NEG | remembered | he-SUJET | never | let | him-SUJET | through | the torment of the cross | kill; |

... He never remembered that he had let him be executed on the cross; (CMORM,I,68.612)

| ... | forrži | žatt | ʒho | Ne | maʒʒ | himm | nowwhar | findenn. |

| ... | therefore | that | you-SUJET | NEG | may | him-OBJET | nowhere | finden. |

... therefore you cannot find him anywhere. (CMORM,I,42.435)

| ... | ža | ne | cušen | ha | neauer | stutten | hare | cleppen. |

| ... | then | NEG | could | they-SUJET | never | answer | his | call-OBJET. |

... they could never be able to answer his call. (CMANCRIW,II.59.589)

| & | žach | žurch | me | ne | schulde | hit | neauer | beon | iupped. |

| & | then | because | me | NEG | should | it-SUJET | never | be | opened-P.PASSE. |

an then, because of me, it should never be opened. (CMANCRIW,II.70.795)

| thanne | ne | mowen | neither | of | hem | ben | parfit, | so | as | eyther | of | hem | lakketh | to | othir. |

| than | NEG | might | neither | of | them-SUJET | be | perfect, | so | as | either | of | them-SUJET | find fault with-PRES | to | other. |

... none of them could be perfect, so that none of them would find fault with the other. (CMBOETH,432.C2.172)

| and | certes, | that | ne | may | nevere | been | accompliced; |

| and | certainly, | that-SUJET | NEG | may | never | be | accomplished-P.PASSE; |

and that certainly cannot be accomplished; (CMCTMELI,222.C1.201)

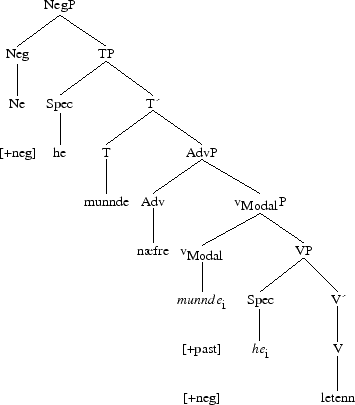

Besides the examples that can be found with the particle ne, we can also find some where ne is used conjointly with not (see the next section) or a negative element different from not (Example (395)). Both negative concord and Neg criterion apply. As for the OE period, let us illustrate this in ME with Structures (397.b) (which refers to Example (391) for early ME) and (398.b) (refering to Example (396) for late ME):

| Ne | munnde | he | nęfre | letenn | himm | Žurrh | rodepine | cwellenn; | |

| ... | NEG | remembered | he-SUJET | never | let | him-SUJET | through | the torment of the cross | kill; |

... He never remembered that he had let him be executed on the cross; (CMORM,I,68.612)

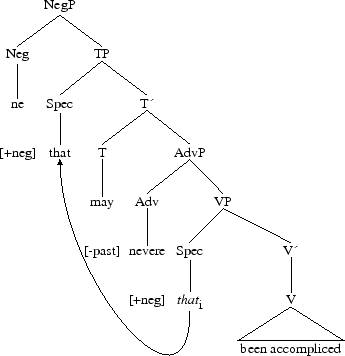

| and | certes, | that | ne | may | nevere | been | accompliced; |

| and | certainly, | that-SUJET | NEG | may | never | be | accomplished-P.PASSE; |

and that certainly cannot be accomplished; (CMCTMELI,222.C1.201)

For both examples, the analysis is the following: the Neg criterion establishes a relation between Neg and T, then there is morphological merge between Neg and T, and finally there is an overt merge of ne with the modals after Vocabulary Insertion.

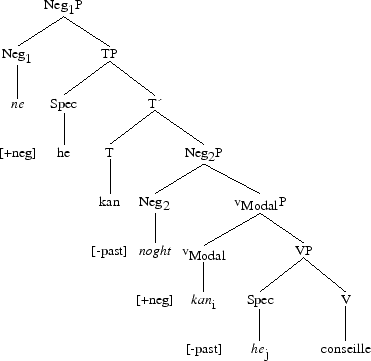

In ME, the coexistence of ne and not is more frequent, even if not prevails over ne. As we have just mentioned, when they coexist within a single sentence, they are to be analyzed as occurrences of negative concord and Neg criterion (as in OE). The following examples illustrate the existence of a second functional head Neg2 which is lower in the structure than Neg1: the latter hosts ne, Neg2, not. Their structure is then:

| & | we | ne | maʒe | naut | žolien | žt | že-SUJET | wint | of | anword | beore-PRES | us-OBJET | towart | heouene. |

| & | we-SUJET | NEG | may | NOT | suffer | that | the | wind | of | calumny | takes | ustoward | heaven. |

& we cannot bear the wind of calumny to take us to heaven. (CMANCRIW,II.100.1203)

| ne | žarf | žu | naut | dreden | žt | attri | neddre | of | helle. |

| NEG | need | you-SUJET | NOT | dread | the | poison | adder-OBJET | of | hell. |

you need not fear the poison of the adder of hell. (CMANCRIW,II.108.1355)

| for | he | ne | kan | noght | conseille | but | after | his | owene | lust | and | his | affeccioun. |

| for | he-SUJET | NEG | can | NOT | advise | but | fir | his | own | lust | and | his | affection. |

for he is unable to give advice but for his own pleasure and affection. (CMCTMELI,223.C2.251)

| Certes, | quod | she, | the | wordes | of | the | phisiciens | ne | sholde | nat | han | been | understonden | in | thys | wise. |

| Certainly, | said-PRET | she-SUJET, | the | words-SUJET PL | of | the | physicians-PL | NEG | should | NOT | have | been-P.PASSE | understood-P.PASSE | in | this | way. |

Certainly, she said, the words of the physicians do not have to be understood this way. (CMCTMELI,226.C2.360)