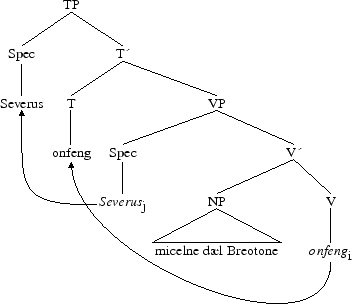

Old English (hence OE) is a SOV language (the Germanic languages are OV/VO) with a head-final parameter: whatever the projection, the complement will precede the head (except for COMP whose complement is on its right).

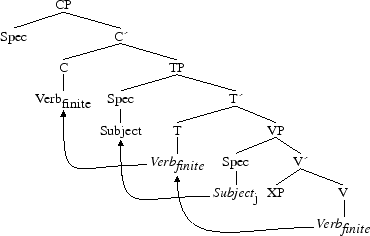

It is also a V2 language: the finite verb raises to the second position of the sentence, whereas the topic on its left can be any element of the sentence. We shall first follow (49) ((49))“s analysis on the OE sentence as an IP-V2 structure, i.e. the finite verb raises from V (its base-position) to I (or T) (the second position). That is what happens when we have a simple (or matrix) sentence, where TP is equivalent to IP.

| Seuerus | se | casere | onfeng | micelne | dęl | Breotene... |

| Severus-NOM | the-NOM | emperor-NOM | received-IND.PRET | great-ACC | part-ACC | Brittany-GEN... |

Severus the emperor received a great part of Brittany... (cobede,BedeHead:1.6.14.6)

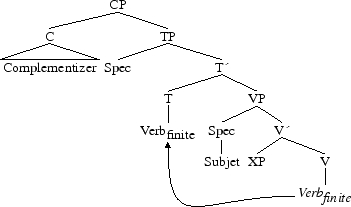

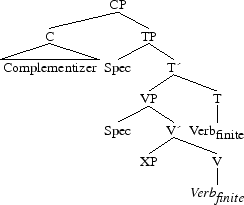

In an embedded clause, we always have an IP-V2 structure. But for Pintzuk, there are two variants of this structure: an INFL-medial (7.a) and an INFL-final (7.b) ones.

| ... | že | god | worhte | žurh | hine... |

| ... | which | God | wrought | through | him... |

INFL-medial structure:

[C že [TP godj [T worhte [VP tj žurh hine [V ti]]]]]

INFL-final structure:

[C že [TP godj [VP tj žurh hine [V ti [T weorhte [PP žurh hine]]]]]]

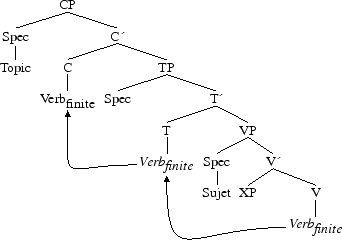

And finally, for a small number of sentences (questions, sentences whose topic is a negative element or the time adverbs ža or žonne), we find a CP-V2 structure: the finite verb raises from V to T and to C, where Spec,CP is realized.

| Ša | gewęnde | seo | wydewe | ham... |

| Then | went-PRET | the-NOM | widow-NOM | back home... |

Then, the widow went back home... (coaelive,ĘLS_[Eugenia]:144.277)

Before dealing with the analysis of the Old English preterite present verbs, let us give the syntactic structures of some types of verbs, which we are to use in the course of our work. They all follow the same pattern: Subject + Finite Verb + Non finite Verb.

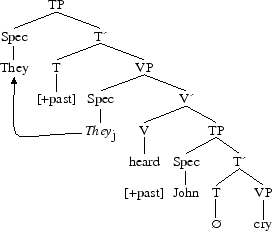

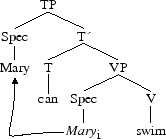

In contemporary English (CE), there are two types of verbs: lexical verbs and operator verbs. Among these different verbs, we can find control, raising or causative ones, or verbs whose complement is a TP.

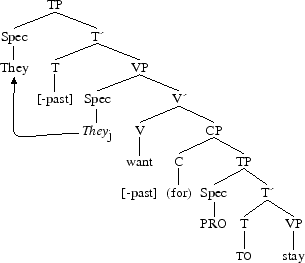

A control structure is a structure whose infinitive clause has a PRO subject controlled by its antecedant:

They want to stay.

where the complement of the finite verb is a CP.

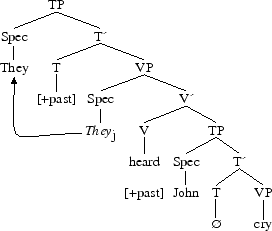

In Example (14.a), the complement of the finite verb is a TP.

They heard John cry

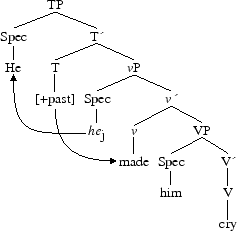

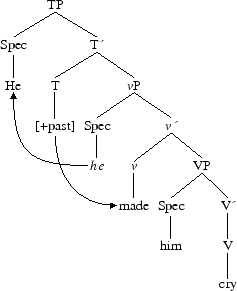

As for causative verbs, they are operator verbs: they are part of the event, but they are not the event; they introduce a notion of cause to the event. These are verbs such as make, have or cause in CE.

He made him cry.

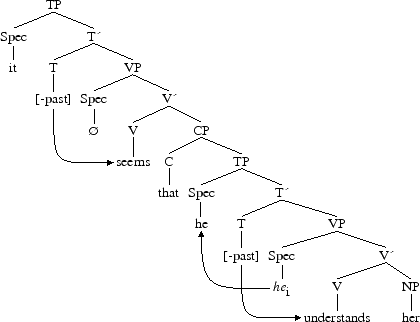

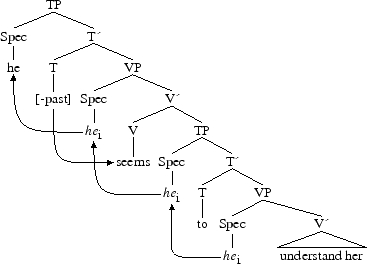

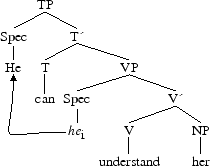

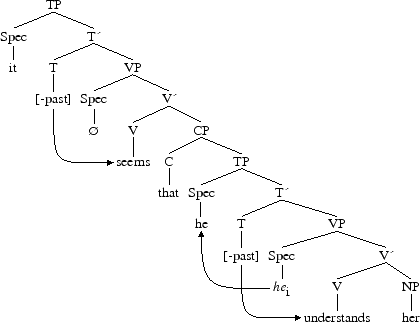

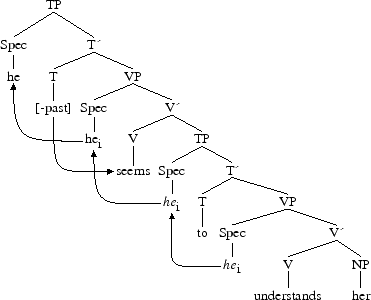

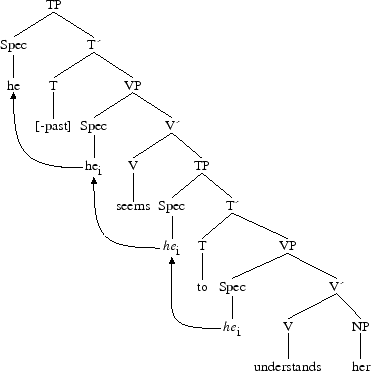

At last, we can find raising structures. In CE, a raising verb lacks an external argument (i.e. a subject) and does not case-assign its complement, which generally is an infinitive clause. A raising verb is a lexical one such as seem or appear in CE. Moreover, modals can be found amongst raising verbs, and we assume modal verbs to be base-generated under T.

It seems that he understands her.

He seems to understand her.

He can understand her.

We kindly ask the reader to keep these structures in mind as we shall go back to them when analysing the preterite presents in parallel with causative verbs and raising structures.

In Old English, there are two main classes of verbs: strong and weak verbs(note: ➳). The class of preterite present verbs is a particular one to which we shall add the anomal verb WILLAN.

Preterite presents are verbs which morphologically have a perfect form but a present meaning (for instance, “I have got” in CE); WILLAN is an athematic verb, i.e. lacking a theme (note: ➳))

in *-mi: the first person singular for the indicative present was *-mi in Indo-European and in Germanic (bio-m en VA “I am”).

The verbs we are focusing on are the following (we shall follow Mossé“s classification from class 1 to class 6 (note: ➳) ((45) ((45)): 118-21):

Class 1: WITAN know, AGAN (note: ➳) have, possess.

Class 2: *DUGAN exist, be useful (note: ➳)

Class 3: UNNAN grant, CUNNAN be able, can, know, ŠURFAN need, be necessary, DURRAN dare.

Class 4: MUNAN remember, *SCULAN be obliged to, should.

Class 6: *MOTAN be allowed to, can.

Non classified: MAGAN be able to (note: ➳).

Anomal verb: WILLAN want.

Present-day Modal verbs are to be found in this class of verbs. In the diachronic literature, it is generally assumed that modal verbs to have “appeared” during the Middle English period. Before that, they were mere lexical verbs identical to the other verbs (see for instance (2) ((2)) ou (59) ((59))).

From a syntactic point of view, we are opposed to this statement given that the changes and evolutions within a language are progressive. So, the hypothesis underlying our analysis is the existence of a specific syntactic position for this class of verbs, as early as the Old English period. This position is different from the one assigned to strong and weak verbs which are base-generated under the head of VP.

Our analysis shall lead us to show that preterite present verbs are base-generated under a specific position we name vModal. Throughout our work, whe shall take into account the complex relations which exist between tense, mood and modality. To achieve this, we shall study their evolution through the use of different texts from different periods of time: Beowulf (cobeowulf in the examples to come) dating back to the 8th century (≃ 680), Bede the Venerable“s Ecclesiastical History (cobede) dating from the 9th-10th centuries (890) and Apollonius of Tyre (coapollo) dating back to the 11th century (1050).

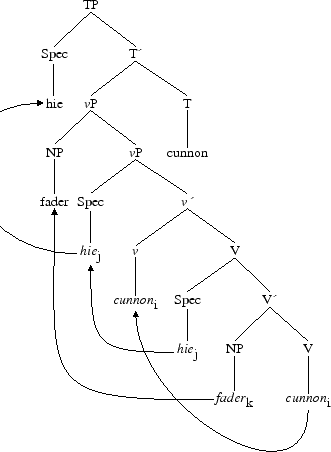

We have just mentioned that OE is an SOV language with a V2 typology. Whether OE is a CP-V2 or an IP-V2 language, the functional heads C, T, (certainly) Neg and v, the head of transitivity, and the lexical head V exist. The analysis to come will allow us to add another head: another v, namely vModal still in the domain of vP.

We shall show the existence of such heads with examples taken from the OE corpus. The following example

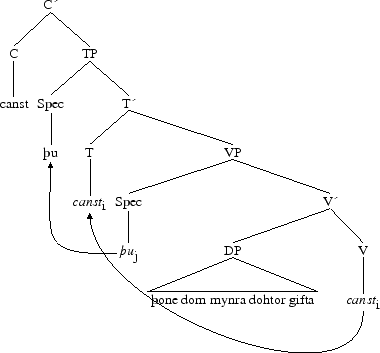

| and | cwęš: | žu | iunga | mann, | canst | šu | žone | dom | mynra | dohtor | gifta? |

| and | said: | you-NOM | young-NOM | man-NOM, | know-IND.PRES | you-NOM | the-ACC | sentence-ACC | my-GEN | daughter-GEN | mariage gift-GEN? |

and said: “Thou young man knowest thou the condition of my daughter“s nuptials?” (coapollo,ApT:4.9.44; 1050)

illustrates Structure (11), and shows the existence of the head C. As for the following example,

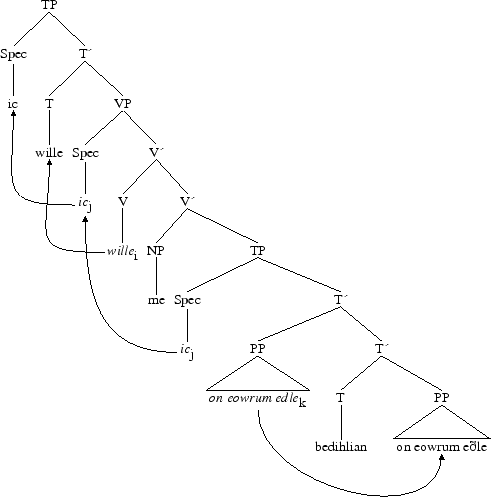

| Foršam | gif | hit | gewuršan | męg, | ic | wille | me | bedihlian | on | eowrum | ešle. |

| Because | if | it-NOM | be | may-IND.PRES, | I-NOM | want-PRES | me | conceal | in | your-DAT | contry-DAT. |

Therefore, if it may be, I will conceal myself in your country. (coapollo,ApT: 9.9.156)

it illustrates Structure (6.b) and shows the existence of the functional head T and the lexical head V.

Let us give some more examples to highlight what has just been said:

| & | he | openlice | sęde | žęt | he | his | bebodum | hyrsumian | ne | wolde. |

| & | he-NOM | openly | said-PRET | that | he-NOM | his | orders-DAT | obey | NEG | want-PRET. |

and he openly said that he did not want to obey his orders. (cobede,Bede_1:7.36.12. 292; 890)

| žonne | sceal | he | hine | eašmodlice | ahabban | from | onsęgdnesse | žęs | halgan | gerynes... |

| then | shall-IND.PRES | he-NOM | him-ACC | respectfully | restrain | from | sacrifice | the-GEN | holy-GEN | sacrament-GEN... |

then he must respectfully restrain himself from sacrifying the holy sacrament... (cobede, Bede_1:16.86.16.784)

| Nolde | eorla | hleo | ęnige | žinga | žone cwealmcuman | cwicne | forlętan. |

| NEG+wanted-PRET | warriors-GEN | protector-NOM | no-INSTR | thing-GEN | murderous guests-ACC | swift-ACC | go off. |

Not for anything the protector of warriors let the murderous guests go off alive. (cobeowul,26.791. 678; 680)

| Ne | meahte | ic | ęt | hilde | mid | Hruntinge | wiht | gewyrcan. |

| NEG | might-PRET | I-NOM | in | fight-DAT | with | Hrunting-DAT | something-ACC | do. |

With Hrunting I might not do anything in the fight. (cobeowul,51.1659.1375)

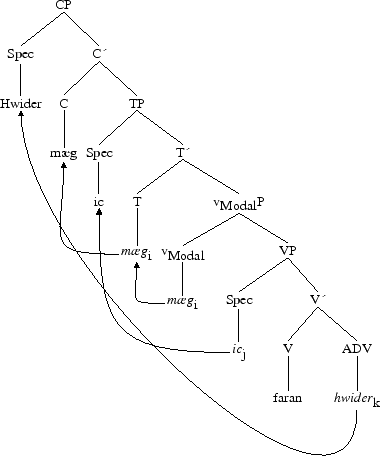

Examples (22) and (25.a) (=(19)) show the existence of the functional head C since we are dealing with CP-V2 structures,

| and | cwęš: | žu | iunga | mann, | canst | šu | žone | dom | mynra | dohtor | gifta? |

| and | said: | you-NOM | young-NOM | man-NOM, | know-IND.PRES | you-NOM | the-ACC | sentence-ACC | my-GEN | daughter-GEN | marriage gift-GEN? |

and said: “Thou young man knowest thou the condition of my daughter“s nuptials?” (coapollo,ApT:4.9.44; 1050)

Indeed, this example shows a CP-V2 structure, with movement of the finite verb from V to T, then from T to C. According to Pintzuk“s analysis ((49) ((49)), chapter 3), the way to know whether the structure is CP-V2 or IP-V2 is to note the position of the subject clitic: if it goes before the finite verb, it is an IP-V2 structure; but if it goes after the finite verb (as illustrated in our example), it is a CP-V2 structure (note: ➳). The constituant order on that kind of sentences (i.e. direct questions, sentences beginning with a negative constituant, or the time adverbs ža and žonne) is derived from the movement of the finite verb from T to C ((49) ((49)): 133).

Example (26.a) (=(20)) underlines the existence of the functional heads T and the lexical head V. This example is an IP-V2 structure.

| Foršam | gif | hit | gewuršan | męg, | ic | wille | me | bedihlian | on | eowrum | ešle. |

| Because | if | it-NOM | be | may-IND.PRES, | I-NOM | want-PRES | me | conceal | in | your-DAT | country-DAT. |

therefore, if it may be, I will conceal myself in your country. (coapollo,ApT:

9.9.156)

For now, we will not go into details concerning this embedded structure. We shall go back to it further on in our work.

OE is generally assumed to be an asymmetrical language: V2 for matrix sentences, but not for embedded sentences since the position C is filled by a lexical complementizer. Pintzuk“s analysis shows that the structure of the OE sentence is IP-V2, both in matrix and embedded sentences (except for the small number of sentences we have just mentioned). She was able to prove the existence of INFL-medial structures for OE embedded sentences (with the finite verb raising from V to T, by analyzing the distribution of particles, pronouns, one-syllable adverbs, as well as the low frequency of the syntactic phenomenon called Verb (Projection) Raising (note: ➳). For embedded sentences, there is the coexistence of two structures: INFL-medial versus INFL-final structures. Within INFL-medial structures, the finite verb raises to T, which is in V2 position; in INFL-final structures, the finite verb also raises to T, but the order within TP is different for the head T is in final position.

Examples (23) and (24 show the existence of the functional head Neg, but not its syntax yet.

The existence of these functional heads allow us to introduce the theoretical framework we are working in: Chomsky“s Minimalist Program. Chomsky defines C and T as belonging to the Core Functional Categories of the sentence. C expresses force and mood and can be unselected (semantic selection); it selects T and has an EPP feature (i.e. a Spec). Concerning T, it must always be (semantically) selected, either by C (and then it possesses a bundle of φ features (features for person, gender and number), or by V,and then T is defective. Moreover T has an EPP feature and it selects V.

Then the structure of a sentence is (CP)-TP-VP, and we shall apply it to the OE examples to follow.

This structure can be applied to the following examples:

| and | cwęš: | žu | iunga | mann, | canst | šu | žone | dom | mynra | dohtor | gifta? |

| and | said: | you-NOM | young-NOM | man-NOM, | know-IND.PRES | you-NOM | the-ACC | sentence-ACC | my-GEN | daugther-GEN | marriage gift-GEN? |

and said: “Thou young man knowest thou the condition of my daughter“s nuptials?” (coapollo,ApT:4.9.44; 1050)

[CP [C canst [TP [Spec šu [T cansti [VP [V cansti žone dom mynra dohtor gifta ?]]]]]]]

| Foršam | gif | hit | gewuršan | męg, | ic | wille | me | bedihlian | on | eowrum | ešle. |

| Because | if | it-NOM | be | may-IND.PRES, | I-NOM | want-PRES | me | conceal | in | your-DAT | country-DAT. |

therefore, if it may be, I will conceal myself in your country. (coapollo,ApT: 9.9.156)

[CP Foršam [C gif [TP hit [VP [V gewuršan [T męg, [TP [Spec ic [T wille [VP [V willei [TP me bedihlian on eowrum ešle.]]]]]]]]]]]]

| Ne | meahte | ic | ęt | hilde | mid | Hruntinge | wiht | gewyrcan. |

| NEG | might-PRET | I-NOM | in | fight-DAT | with | Hrunting-DAT | something-ACC | do. |

With Hrunting I might not do anything in the fight. (cobeowul,51.1659.1375)

[CP [C Ne meahte [TP ic [T meahtei [VP [V meahtei [TP ęt hilde mid Hruntinge wiht gewyrcan.]]]]]]]

At this stage, we shall not go any deeper into the base position of the preterite present verbs.

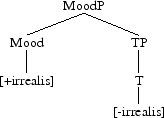

Examples (21), (23) and (24) give an illustration of the present and past forms of the preterite presents, but still we cannot say if these are indicative or subjunctive forms. Indeed, OE had two moods with different endings for each of them. The forms of Examples (19), (20) and (22) are in the indicative mood. If mood can be seen through endings on verbs, it would imply that there are two functional heads for both moods: one for the realis mood and one for the irrealis mood. We assume T to host [-irrealis] mood. But we shall go back to this point further on, once the syntactic position for preterite present verbs is defined.

We have previously mentioned that preterite presents made up a class of verbs on its own, which was different from strong and weak. Why are they different? First, they are all defective (except WILLAN), i.e. they do not possess a complete system of conjugation (see Appendix A). Second, there is a vowel alternation between the infinitive form and the indicative present form which is not found with strong and weak verbs (note: ➳).

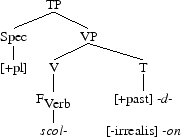

Finally, preterite presents are the only verbs to have a specific ending for all the plural present forms: -on (witon, agon, cunnon, sculon, ..., whereas the lexical verbs have an -aš (nimaš “they take”, demaš “they decide”, habbaš “they have”) ending. They also are specified by the use of a dental suffix in -t(e), -d(e) and -š(e) for the past singular forms, like weak verbs. Preterite presents are built both on strong and weak verbs (note: ➳).

These morphological differences are to be useful for our analysis. Indeed, if they have a specific morphology, the starting point of our analysis can be to grant them a specific syntactic position.

In Examples (19) to (24), we underlined the existence of the heads C, T and V, but we have purposely put aside Neg and the head for the preterite presents.

Let us now focus on them by questioning their base-position.

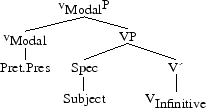

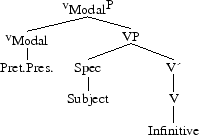

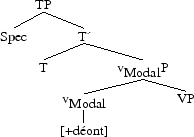

We propose there are two heads for the preterite presents verbs: V, for preterite presents used as lexical verbs, and a modal little v (i.e. vModal) for preterite presents followed by an infinitive complement.

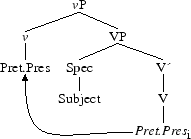

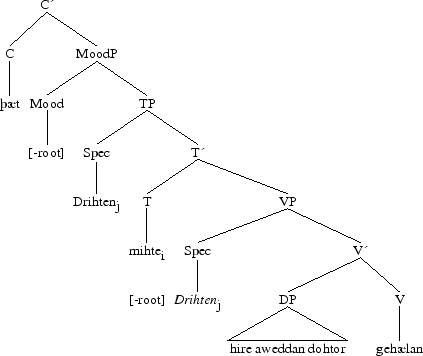

Then, when a preterite present verb is followed by an object, it is base-generated under (lexical) V. It then merges to v and behaves the same way strong and weak verbs do: it is Structure (31). But when it is followed by an infinitive, it is to be considered as a semi-lexical verb (for grammaticalization is not completed yet). As a consequence, it is no longer base-generated under V but under vModal: it is Structure (32). Why assume such a position? All the instances of preterite presents verbs that have been found in the corpus are either to have a root reading or an epistemic reading (but we shall go back to this in further details in Section 2.8.2). We then have the following two verbal structures: (31) when the preterite present is lexical and (32) when it is semi-lexical:

In the examples to come, the preterite present is used alone (i.e. lexically):

| No | hie | fęder | cunnon, | ... |

| No | they-NOM | father-ACC | know-IND.PRES, | ... |

They know of no father, ... (cobeowul,42.1355.1119; 680)

| Ac | sio | šeod | žone | cręft | žęs | fiscažes | ne | cuše, | ... |

| But | the-NOM | people-NOM | the-ACC | craft-ACC | the-GEN | fishing-GEN | NEG | knew-PRET, | ... |

But the people did not know the craft of fishing, ... (cobede,Bede_4:17.304.10.3076; 890)

| ic | secge | še | to sošan | žone | forlidenan | man | ic | wille. |

| I-NOM | say-IND.PRES | he-NOM | in sooth | the-ACC | shipwrecked-ACC | man-ACC | I-NOM | want-PRES |

I will say to thee in sooth that I desire the shipwrecked manJ. (coapollo,ApT:20.15. 427)

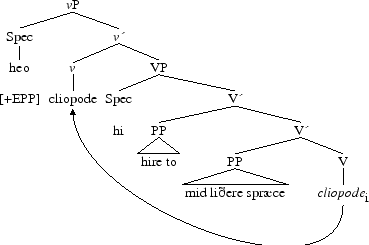

Let us take again Example (33) (now (36.a)) and give its structure where CUNNAN is first base-generated under V, then merges under v then T:

| No | hie | fęder | cunnon, | ... |

| No | they-NOM | father-ACC | know-IND.PRES, | ... |

They know of no father, ... (cobeowul,42.1355.1119; 680)

In most cases, the preterite present verb is followed by an infinitive (a strong or a weak verb, or another preterite present (in italics):

| Nu | ic | eower | sceal | frumcyn | witan, | ... |

| Now | I-NOM | you-ACC | shall-IND.PRES | ancestors-ACC | know, | ... |

Now I must learn your lineage, ... (cobeowul,10.251.203; 680)

| Ic | to | sę | wille | wiš | wraš | werod | wearde | healdan. |

| I-NOM | to | sea-DAT | PRES | against | wrath-ACC | hosts-ACC | watcher-ACC | keep. |

I shall go back to the sea to keep watch against hostile hosts. (cobeowul,12.318.257)

| Wille | ic | asecgan | sunu | Healfdenes, | męrum | žeodne, | min | ęrende, | aldre | žinum, | gif | he | us | geunnan | wile | žęt | we | hine | swa | godne | gretan | moton. |

| will-PRES | I-NOM | dire | son-DAT | Healfdene-GEN, | great-DAT | prince-DAT, | my-ACC | errand-ACC, | lord-DAT | your-DAT, | if | he-NOM | us-DAT | grant | wants-PRES | that | we-NOM | him-ACC | thus | kindness-ACC | address | shall-IND.PRES. |

I will tell my errand to Healfdene“s son, the great prince your lord, if, good as he is, he will grant that we might address him. (cobeowul,13.344.285)

| ac | wit | on | niht | sculon | secge | ofersittan, | ... |

| but | the two of us-NOM | at | night-ACC | shall-IND.PRES | sword-ACC | forgo, | ... |

but we shall forgo the sword in the night, ... (cobeowul,22.681. 575)

| ... | žęt | he | wiš | ęlfylcum | eželstolas | healdan | cuše, | ša | węs | Hygelac | dead. |

| ... | that | he-NOM | against | foreigners-DAT | native throne-ACC | hold | could-PRET, | since | was-IND.PRET | Hygelac-NOM | dead-NOM. |

... that he could hold his native throne against foreigners now that Hygelac was dead. (cobeowul,73.2367.1931)

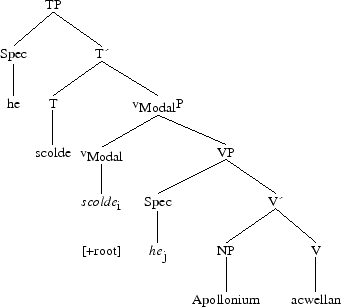

| he | scolde | eašmodlice | for | heo | žingian, | žęt | heo | ne | žorfte | in | swa | frecne | sišfęt | & | in | swa | gewinfulne | & | in | swa | uncuše | elžeodignesse | faran. |

| he-NOM | might-PRET | humbly | for | her-ACC | ask, | so that | she-NOM | NEG | needed-PRET | in | so | dangerous-ACC | journey-ACC | & | in | so | toilsome-ACC | & | in | so | incertain-ACC | pilgrimage-ACC | go. |

that he might, by humble entreaty, obtain (of the Holy Gregory), that they should not be compelled to undertake so dangerous, toilsome, and uncertain a journey. (cobede,Bede_1:13.56. 6.521; 890)

| Ic | gehyhte | & | wende, | žęt | wit | nu | hraše | scoldon | ętgędre | in | ece | liif | gongan. |

| I-NOM | hoped-IND.PRET | & | believed-IND.PRET, | that | both-NOM | now | swiftly | should-IND.PRET | ensemble | dans | eternal-ACC | life-ACC | go. |

I was in hopes that we should have entered together into life everlasting. (cobede,Bede_3:19.244.7.2499)

| ...žęt | he | swa | in | toweardnesse | ecelice | ricsian | mid | Criste | moste. |

| ...that | he-NOM | so | in | hereafterr | eternally | reign | with | Christ-DAT | pouvait-PRET. |

... so you will hereafter reign in Christ. (cobede,Bede_3:21.248.21. 2544)

| ... | ond | hy | ealle | ža | bliše | mode | lustlice | healdon | woldon... |

| ... | and | they-NOM | all-NOM | this-ACC | cheerful-INSTR | mind-INSTR | willingly | wanted-IND.PRET. |

... and they would all most willingly observe (it) with a cheerful mind... (cobede, Bede_4:5.276.32.2812)

| Gif | hit | nęnge | žinga | to dęge | beon | męgge. |

| If | that-NOM | no-INSTR | thing-GEN | today-DAT | be | might-SUBJ.PRES. |

If today that might happen with none of these things. (cobede,Bede_4: 12.290.20.2932)

| ... | žęt | nęnig | šara | onweardra | his | heortan | degolnessa | him | helan | dorste... |

| ... | that | no-one-NOM | the-GEN | opponants-GEN | his | heart-GEN | secret-ACC | him-DAT | conceal | dared-PRET... |

... none of the opponants dared to conceal the secret of his heart... (cobede,Bede_4:28.362.27.3643)

| and | gif | šu | žęt | ne | dest, | žu | scealt | oncnawan | žone | gesettan | dom. |

| and | if | you-NOM | this-ACC | NEG | do-IND.PRES, | you-NOM | shall-IND.PRES | understand | the-ACC | appointed-P.PASSE-ACC | sentence-ACC. |

and if thou doest that not, thou shalt suffer the appointed doom. (coapollo,ApT:5.5. 71; 1050)

| Hlaford | Apolloni, | gif | šu | žissere | hungrigan | ceasterwaru | gehelpest, | na | žęt | an | žęt | we | willaš | žinne | fleam | bediglian... |

| Lord-NOM | Apollonius, | if | you-NOM | these | hungry | citizens | help-IND.PRES, | no at all | this-DAT | only | that | we-NOM | will-IND.PRES | this-ACC | flight-ACC | conceal. |

Lord Apollonius, if thou helpest these hungry citizens, we will not only conceal thy flight, ... (coapollo,ApT:9.18.164)

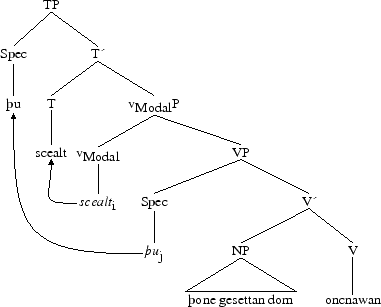

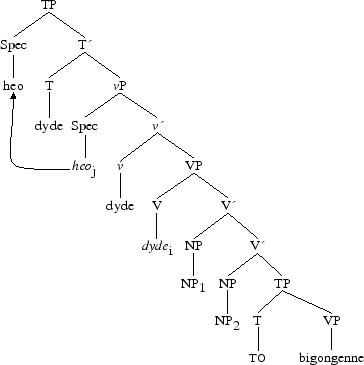

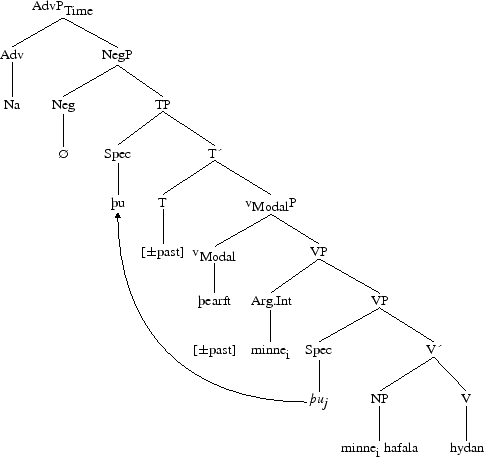

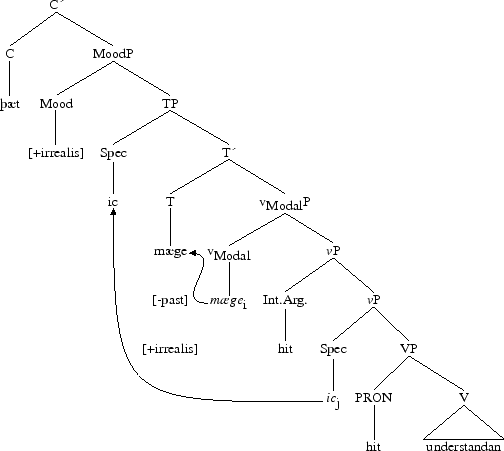

Let us illustrate Structure (32) with Example (48) (now (50.a)):

| and | gif | šu | žęt | ne | dest, | žu | scealt | oncnawan | žone | gesettan | dom. |

| and | if | you-NOM | this-ACC | NEG | do-IND.PRES, | you-NOM | shall-IND.PRES | understand | the-ACC | appointed-P.PASSE-ACC | sentence-ACC. |

and if thou doest that not, thou shalt suffer the appointed doom. (coapollo,ApT:5.5. 71; 1050)

When we are dealing with negation, the adverbial negative particle ne (following the terminology used in the diachronic literature) immediately precedes the finite verb,

| ... | no | šu | ymb | mines | ne | žearft | lices | feorme | leng | sorgian. |

| ... | no | you-NOM | about | me-GEN | NEG | needs-IND.PRES | body-GEN | comfort through food-DAT | longer | trouble. |

... no longer will you need trouble yourself to take care of my body. (cobeowul,16.448.374; 680)

| ša | hine | Wedera | cyn | for | herebrogan | habban | ne | mihte. |

| after | the-ACC | Weather-Geats-GEN | people-NOM | because of | fear of war-DAT | keep | NEG | might-PRET. |

After that the country of the Weather-Geats might not keep him. (cobeowul,16.459.386)

| Ša | ne | meahte | he | eašelice | ža | unstillnesse | onfallendra | mengu | aberan... |

| Then | NEG | could-PRET | he-NOM | easily | the-ACC | agitation-ACC | oppressing-GEROND-GEN | crowd-GEN | bear... |

he could no longer bear the crowds that resorted to him... (cobede,Bede_3:14.216.32.2220; 890)

| ac | he | ne | mihte | hine | žar | findan | on | šam | flocce. |

| but | he-NOM | NEG | could-PRET | him-ACC | there | find | in | the | troops-DAT. |

but he could not find him in the company. (coapollo,ApT:13.9.232)

Moreover, this adverbial particle merges with that specific class of verbs (to be more accurate, it merges with AGAN, WILLAN and WITAN (note: ➳)):

| and | hi | noldon | me | ža | agifan. |

| and | they-NOM | NEG+wanted-IND.PRET | me | her-ACC | restore. |

and they would not restore her to me. (coapollo,ApT:50.10.534; 1050)

| Nat | he | žara | goda | žęt | he | me | ongean | slea. |

| NEG+knows-PRES | he-NOM | these-GEN | tools-GEN | that | he-NOM | me-DAT | against | strike-SUBJ.PRES. |

He knows no good tolls with which he might strike against me. (cobeowul,22.681.574; 680)

| ... | žęt | he | ža | weoržuncge | Eastrena | on riht | ne | heold | ne | nyste. |

| ... | what | he-NOM | the-ACC | observance-ACC | Easter-GEN | correct-ACC | NEG | respected-IND.PRET | nor | NEG+knew-PRET. |

... what he imperfectly understood in relation to the observance of Easter. (cobede, Bede_3:14.206.1.2087; 890)

What is striking is that merging only happens with this specific class of verbs (even if it is not compulsory), but not with strong and weak verbs (except with wesan and habban).

Let us sum up their differences:

They have a specific relationship with negation since ne can merge with the preterite present.

They are morphologically different from the other classes of verbs (as far as their endings are concerned). The plural form of the indicative present is not the strong or weak verbs; furthermore, there is a vowel alternation between the infinitive and the present indicative forms.

The preterite present verbs can generally take

an object NP (either noun or pronoun), like any other class of verbs,

a VP where there is an infinitive verb (for strong and weak verbs, it belongs either to TP or CP).

as a complement.

When an infinitive follows a lexical verb (strong or weak), it belongs to TP or CP, according to the type of verb one is dealing with. We shall analyze this in more detail in the next section (note: ➳)

| Ža | het | he | hraše | his | žegnas | hine | secan | & | acsian. |

| Then | ordered-IND.PRET | he-NOM | immediately | his | soldiers-ACC | him-ACC | seek | & | call. |

Whereupon he sent some soldiers to make a strict search after him. (cobede,Bede_1:7.34.25.280)

| ... | žęt | seolfe | he | ne | blinnež | męrsian | & | weoržian | a | butan ende... |

| ... | that | self-NOM | he-NOM | NEG | ceases-IND.PRES | glorify | & | celebrate | always | ever. |

... or rather never ceases to celebrate... (cobede, Bede_5:20.474.6.4756)

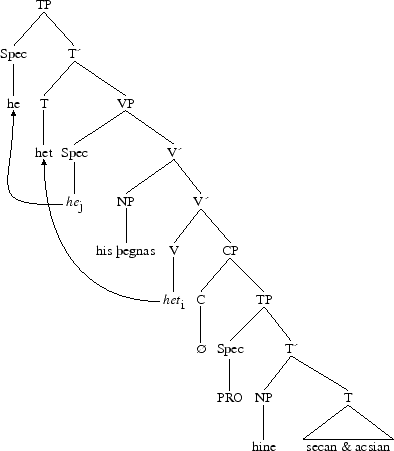

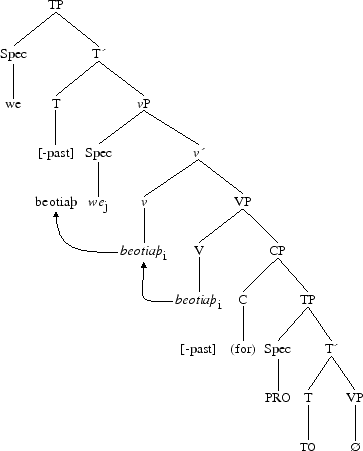

Let us take Example (59) (now (61.a)) and give its structure (which will be identical for Example (60)).

| Ža | het | he | hraše | his | žegnas | hine | secan | & | acsian. |

| Then | ordered-IND.PRET | he-NOM | immediately | his | soldiers-ACC | him-ACC | seek | & | call. |

Whereupon he sent some soldiers to make a strict search after him. (cobede,Bede_1:7.34.25.280)

All the given examples allow us to say that preterite presents are base-generated under V when they are lexical. But when they are semi-lexical, they are base-generated under vModal. We further assume that they are raising verbs with a structure very close to the CE causative structures. They do behave like operators: they are part of the event of the sentence but they are not the event (because of that, they are said to be “causative”). Moreover, they do not have an external argument (i.e. a subject, the visible subject is the subject of the infinitive verb) and they do not case-assign their complement. Subject and object are assigned θ-roles by the infinitive. Still, agreement is visible between the subject and the preterite present.

At the beginning of this chapter, we have defined three functional heads (C, T and Neg (even if we have not defined the syntactic position of the latter)) by means of examples. We are now going to define a fourth functional head – little v – which also belongs to the CFCs of a phase. In (10) ((10)): 15, v is a “light” verb, head of transitive structures. It must always be selected by the functional category T. In its turn, it selects a VP and an NP (i.e. the external argument of v). It has an EPP feature as C and T do. Moreover, within the minimalist framework, C and v define the strong phases of a derivation. Let us point out that fact in OE.

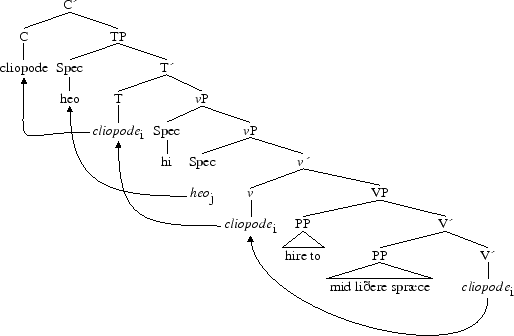

| ... | ža | cliopode | heo | hi | hire | to | mid | lišere | spręce... |

| ... | then | called-PRET | she-NOM | her-ACC | her-DAT | to | with | gentle-DAT | speech-DAT. |

then she called her to her with gentle speech... (coapollo,ApT:2.14.24)

The structure of this sentence is the following:

In this structure, there are two strong phases vP and C. The speaker first chooses elements which correspond to a (lexical or grammatical) category from his/her lexicon. Both the verb and its complements are generated under VP which has semantically been selected by v. This is why V merges with v the head of transitivity of the (strong) phase. Then, the subject in Spec,vP satisfies the EPP feature of TP. Next, an additional Spec is adjoined to vP for the internal argument.

The speaker then chooses the following elements in his/her lexicon:

V = cliopode [+past,-irréel,+sg3],

NPSubject = heo [+sg3,+fem,+nom],

NPObject = hi [+sg3,+masc,+acc],

PP = hire to [+sg3,+fem,+dat],

PP = mid lišere spręce [+dat].

Next, the chosen components combine with one another:

At this point of the derivation, it can still crash because the tense features of the verb and T are not satisfied yet. As a consequence, the derivation cannot be spelled out. So, v is to merge with T to satisfy the uninterpretable tense features of T, and the subject in Spec,vP is to raise to Spec,TP to satisfy the φ features of T. Once satisfied, the tense features and the φ features of the subject are erased/cancelled. But still, there is no Spell-Out since TP is not a strong phase. As we have just said, T is semantically selected by C. Merge of the time adverb ža under Spec,CP triggers movement from v to C. The derivation is now over and can be spelled out.

So, we have just underllined the existence of v, another functional head. But we shall question Neg later in our work.

Within Halle et Marantz“s Distributed Morphology (DM), and more particularly in (43) ((43)), v has the following features:

It creates a verb.

It provides event semantics.

It provides agentive semantics for agentive constructions.

It merges with an external argument.

There is an Agree relation with the object.

According to Marantz, Features 1 to 3 go together, i.e. the semantic content of v acts on the semantic content of the sentence. For a specific v, we can have Features 1 to 3 without Features 4 and 5, as we can have Features 4 and 5 without Features 2 and 3.

Following our hypothesis, vModal has Features 1, 2 and 3: it creates the preterite present which is a semi-lexical verb (that we can consider as an “operator”; it provides event semantics (it adds up information to the relation set by the non finite verb); and it might provide agentive semantics (yet, can a raising verb provide agentive semantics?). But vModal does not have Features 4 and 5 because the external argument merges with the non finite verb, and because there is no Agree relation with the infinitive verb to which it does not assign case.

Up to now, we have postulated the existence of two syntactic positions for the preterite presents:

The position V when the preterite present is direct transitive (followed by an NP), indirect transitive (followed by a PP) or bitransitive (followed by two objects).

the position we have named vModal when the preterite present is transitive (the complement is an infinitive, i.e. a VP). This latter position is lower than T.

For the sake of our analysis, it is necessary to define what an infinitive structure is and what the differences are when the finite verb is either lexical or semi-lexical.

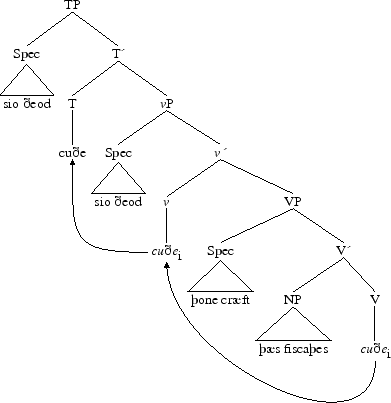

The analysis we carried out in the past section allows us to say two syntactic positions exist in OE for preterite present verbs depending on their lexical or semi-lexical use. When lexical, the syntactic position is V; when semi-lexical, the syntactic position is vModal. The following example illustrates the first position. But in both cases, the subject is generated under Spec,vP (but when vP is tacit, the subject is under Spec,VP).

| Ac | sio | šeod | žone | cręft | žęs | fiscažes | ne | cuše, | ... |

| But | the-NOM | people-NOM | the-ACC | craft-ACC | the-GEN | fishing-GEN | NEG | knew-PRET, | ... |

But the people did not know the craft of fishing, ... (cobede,Bede_4:17.304.

10.3076; 890)

When a preterite present does not have a NP complement, it is VP where the infinitive verb is.

Let us have a close look at the infinitive structures where there is either a lexical or a semi-lexical verb, so that we can define the differences between these two types of verbs.

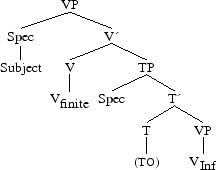

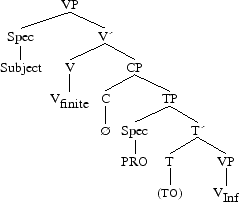

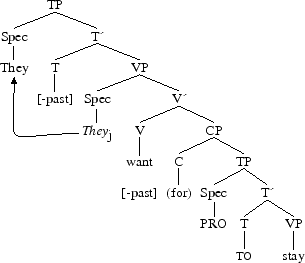

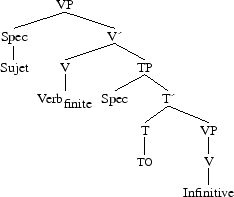

In CE, infinitive clauses have the following structures, with a lexical verb with TO ((66.b)) or without TO ((67.b)); or with a modal verb (68.b)):

They want to stay.

They heard John cry.

Mary can swim.

The infinitive verb is the complement for the modal and it is base-generated under VP. As for the other types of infinitives where the finite verb is lexical, they are clauses, that is a complex sentence with a finite and non finite verb. Concerning the lexical V, it does not raise to T, but it is the tense affix that lowers to V. This is Affix Hopping.

Now, what about Old English? Do infinitive clauses belong to a VP (which is our hypothesis)? Before analyzing these clauses, let us first focus on infinitives following a finite lexical verb.

From the OE period, we can find two types of infinitive clauses: the ones introduced by TO (Examples (69) to (75)), and the ones which are not introduced by TO (Examples (59) and (60)).

| ręd | eahtedon | hwęt | swišferhšum | selest | węre | wiš | fęrgryrum | to | gefremmanne. |

| plan-ACC | soughtt-IND.PRET | what-NOM | strong-hearted-DAT | the best-NOM | was-SUBJ.PRET | avec | awfulness-DAT | TO | follow-DAT. |

sought a plan, what would be best for strong-hearted men to do against the awful attacks. (cobeowul,8.171.138)

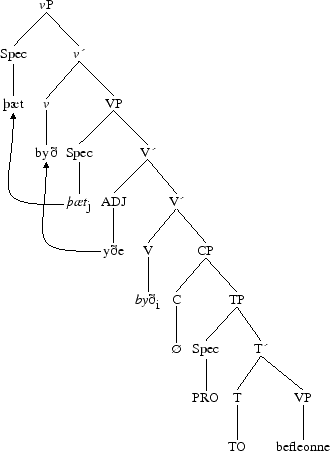

| No | žęt | yše | byš | to | befleonne... |

| No | that-NOM | easy-NOM | is-IND.PRES | TO | flee-DAT. |

That is not easy to flee from... (cobeowul,32.1002.835)

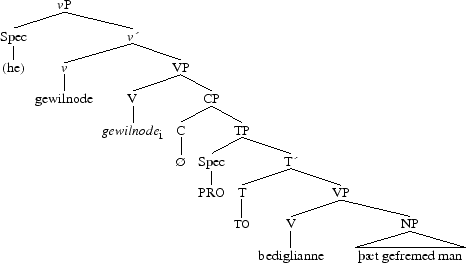

| and | žęt | gefremed | man | gewilnode | to | bediglianne. |

| and | that-ACC | stranger-ACC | man-ACC | wanted-PRET | TO | conceal-DAT. |

and he wanted to conceal that stranger. (coapollo,ApT:1.14.13)

| willaž | žęt | gewrecan | gif | we | magon, | žeah | we | beotiaž | to | ∅. |

| want-IND.PRES | that-ACC | revenge | if | we | can-IND.PRES, | even if | we-NOM | threaten-IND.PRES | TO | ∅. |

and desire, if we can, to take revenge, and (if we are unable), we nevertheless threaten to do so. (coblick, HomS_10_[BlHom_3]:33.127.447)

| & | het | him | to | gelangian | ža | ylcan | Gotan. |

| & | ordored-IND.PRET | him-DAT | TO | send | the-ACC | same-ACC | Goths-ACC. |

& he ordered him to send for the same Goths. (cogregdH,GD_1_[H]:10.80.10.794)

| Eft | žęs | on | mergen | het | se | manfulla | dema | ža | eadigan | Agnen | him | to | gefeccan. |

| Again | this-GEN | on | morning-ACC | ordered-IND.PRET | le-NOM | wicked-NOM | judge-NOM | the-ACC | saint | Agnes-ACC | him-DAT | TO | seek. |

The morning after, the wicked judge ordered Saint AGnes to be sought for again. (coaelive,ĘLS[Agnes]:91.1774)

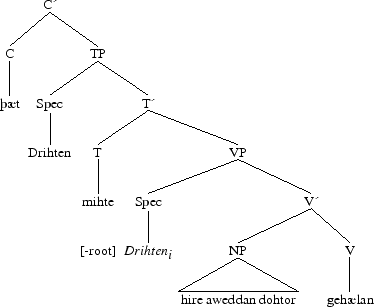

| Ša | cwęš | to | him | ožer | of | hys | leorningcnihtum, | Drihten, | alyfe | me | ęrest | to | farenne | & | ∅ | bebyrigean | minne | fęder. |

| Then | said-IND.PRET | to | him-DAT | other-NOM | of | his | disciples-DAT, | Lord-NOM, | allow-SUBJ.PRES | me | before | TO | go-DAT | & | ∅ | bury | my-ACC | father-ACC. |

Another of his disciples then said to him: “may the Lord allow me first to go and bury my father”. (cowsgosp,Mt_[WSCp]:8.21.462)

If we look closely at these examples, we can notice that when an infinitive clause is introduced by TO, the infinitive can be marked dative, which does not seem to be the case when TO is absent. We noticed this in Example (72): there is an ellipsis of the non finite verb, which would show that TO becomes a functional head (we shall explore that later in our work). On the contrary, in Example (73), the infinitive is unmarked. We can then wonder what this TO syntactically stands for: is it the well-known functional head in CE, is it a preposition governing the dative case, or is it a semi-lexical item which will lead us to say that TO follows the same syntactic path preterite presents do? In view of the preceding examples, we can consider TO as a semi-lexical preposition (i.e. undergoing grammaticalization) governing the dative case (see (62) ((62))). Yet, the syntactic representation of this element would be the functional head T having a [+dat] feature which is checked out by the [+dat] feature of the infinitive (if this feature is marked).

Let us now illustrate what we have just said with the following three examples: (76) where TO is not present, (77) where TO precedes the non finite verb, and (79.a) where PRO the subject of the infinitive is controlled by the subject of the sentence.

| Ža | het | he | hraše | his | žegnas | hine | secan | & | acsian. |

| Then | ordered-IND.PRET | he-NOM | immediately | his | soldiers-ACC | him-ACC | seek | & | call. |

Whereupon he sent some soldiers to make a strict search after him. (cobede,Bede_1:7.34.25.280)

| and | žęt | gefremed | man | gewilnode | to | bediglianne. |

| and | this-ACC | stranger-ACC | man-ACC | wished-PRET | TO | conceal. |

and the perpetrated crime sought to conceal. (coapollo,ApT:1.14.13)

Whose structure is,

As for the example

| No | žęt | yše | byš | to | befleonne... |

| No-NOM | easy-NOM | is-IND.PRES | TO | flee-DAT. |

That is not easy to flee from... (cobeowul,32.1002.835)

In Examples (80) to (84),we give again instances of preterite presents followed by an infinitive, in Examples (80) to (82), they are followed by an infinitive clause where the non finite is realized; but in Examples (83) to (84), there is an ellipsis of the non finite verb.

| ne | mihte | snotor | hęleš | wean | onwendan. |

| NEG | could-PRET | wise-NOM | hero-NOM | sadness-ACC | change. |

nor might the wise warrior set aside his woe. (cobeowul,8.189.153)

| ic | gešristlęhte | žęt | ic | dorste | žis | weorc | ongynnan. |

| I-NOM | assumed-PRET | that | I-NOM | dared-PRET | this-ACC | work-ACC | begin. |

I assumed I dared to begin this work. (cobede,BedePref:4.10.163)

| and | hi | noldon | me | ža | agifan. |

| and | they-NOM | NEG+wanted-IND.PRET | me | her-DAT | restore. |

and they would not restore her to me. (coapollo,ApT:50.10.534)

| cwęš | heo: | Wilt | šu, | wit unc | abidde | ondrincan. | Cwęš | ic: | Ic | wille | ∅... |

| said-IND.PRET | she-NOM: | want-IND.PRES | you-NOM, | me and you-NOM | call-SUBJ.PRES | drink. | said-IND.PRET | I-NOM: | I-NOM | want-PRES | ∅... |

she said, “Would you like me to call for something to drink?“ - “Yes,“ said I, “and am very glad if you can.“ (cobede,Bede_5:3.392.32.3921)

| unc | sceal | worn | fela | mažma | gemęnra | ∅, | sižšan | morgen | biš. |

| we-DAT | shall-IND.PRES | a lot-NOM | many | treasures-GEN | precious-GEN | ∅, | since | morning-NOM | is-IND.PRES. |

many of our treasures will be shared when morning comes. (cobeowul,55.1782.1472)

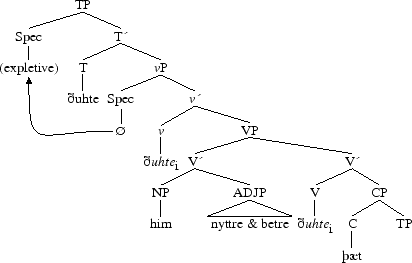

In contemporary English, causative verbs are operator verbs: they are neither lexical nor auxiliary verbs, they are part of the event but they are not the event. A causative verb is a v having the features 1 to 5 we have already mentioned in Section2.4.1: it creates a verb, provides event and agentive semantics, merges with an external argument and has an Agree relation with an object. Let us give some examples of causative verbs again in CE, then let us focus on OE to see if we can find such instances.

He had them eat the cake.

He made him cry.

The structure of (86) is,

In CE causative structures, the object of the finite verb is a VP. Is it the same in OE? We have considered the instances of the verb don “cause, do”:

| (...) | doš | foroft | drymen | & | wiccan | on | heora | scincręfte, | to | beswicenne... |

| (...) | cause-IND.PRES | very often | magicians-NOM | & | soothsayers-NOM | by | their | craft-DAT, | TO | deceive-DAT... |

Very often with their craft, the magicians and soothsayers are deceiving... (coaelhom,ĘHom_18:91.2543)

| Žone | ošerne | dęl | he | dyde | ∅ | gehealden | mid | him | to | bebyrgenne | ęfter | his | foršsiše. |

| This-ACC | other-ACC | speech-ACC | he-NOM | caused-PRET | ∅ | follow | with | him-DAT | TO | bury-DAT | after | his-DAT | death-DAT. |

he had this other speech be followed before him for his burial once he died. (coaelive,ĘLS_[Basil]:123.531)

| and | dydon | on | węter | wanhalum | to | žicgenne, | ... |

| and | caused-IND.PRET | opn | water-ACC | stagnant-DAT | TO | drink-DAT, | ... |

and they made (him) drink this stagnant water, ... (coaelive,ĘLS_[Oswald]:200.5496)

| Ond | heo | leornunge | godcundra | gewreota | hire | underžeodde | dyde | to | bigongenne, | ... |

| And | she-NOM | knowledge-DAT | holy-GEN | scriptures-GEN | her-DAT | subjected-P.PASSE-DAT | caused-PRET | TO | attend-DAT, | ... |

And she obliged those who were under her direction to attend so much to reading of the Holy Scriptures, ... (cobede,Bede_4:24.334.16.3354)

the last examples have the following structure which applies to the other examples (even (89) where TO is not visible):

Considering these examples (they are not numerous in the corpus we are using, the infinitive structure of this causative verb is TP in Old english, and not VP like in CE. They are then different from preterite present verbs which have a VP complement.

Let us go back to preterite presents. The (finite) preterite present is followed by an infinitive in (80) to (82). In Examples (83) to (84), the finite verb is alone but there is the ellipsis of the infinitive verb. We will now analyse the structure of these verbs and show that the infinitive complement is indeed a VP. We will then be able to differenciate causative verbs from preterite present verbs and claim that causative verbs are VP whereas preterite presents are vModal (according to the analysis in (43) ((43)), our vModal only has three features out of five, two of them dealing only with semantics). Before starting our analysis, let us give some examples we have already mentioned:

| willaž | žęt | gewrecan | gif | we | magon, | žeah | we | beotiaž | to | ∅. |

| want-IND.PRES | that-ACC | revenge | if | we | can-IND.PRES, | even if | we-NOM | threaten-IND.PRES | TO | ∅. |

and desire, if we can, to take revenge, and (if we are unable), we nevertheless threaten to do so. (coblick,

HomS_10_[BlHom_3]:33.127.448)

| ... | žęt | heo | his | wedenheortnisse | gestilden, | ac | heo | ne | meahton | ∅. |

| ... | that | he-NOM | his | madness | eased-SUBJ.PRET, | but | he-NOM | NEG | could-IND.PRET | ∅. |

... did all he could to assuage the madness of the unfortunate man, but could not prevail. (cobede,Bede_3:9.184.32. 1853)

| unc | sceal | worn | fela | mažma | gemęnra | ∅, | sižšan | morgen | biš. |

| we-DAT | shall-IND.PRES | a lot-NOM | many | treasures-GEN | precious-GEN | ∅, | since | morning-NOM | is-IND.PRES. |

many of our treasures will be shared when morning comes. (cobeowul,55.1782.1472)

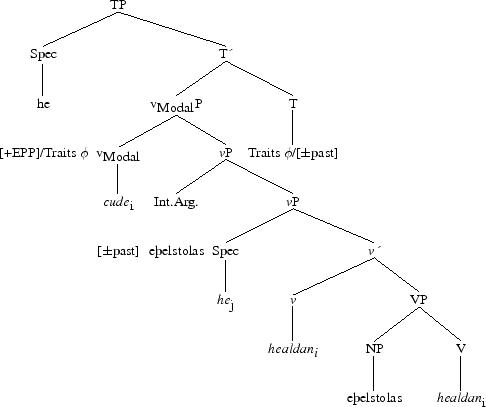

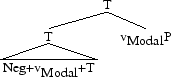

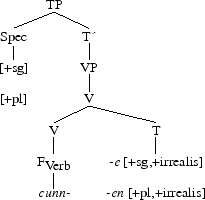

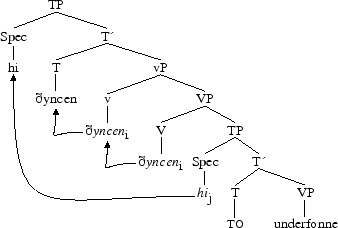

The first step of our analysis is drawing a parallel between Example (93) and Examples (94) to (95). So far, the examples where the infinitive clause was introduced by TO have showed us that TO tended to be a functional head, that is a semi-grammatical preposition. Example (93) confirms this statement: with the ellipsis of the infinitive, TO is considered as a functional head (we assume it is T); if TO had been a preposition, the ellipsis of the infinitive would not have occurred. We then suggest to draw a parallel between this structure, where we assume TO to be base-generated under T, and Structures (94) to (95). This analysis will allow us to show that vModal is the syntactic position where preterite presents are base-generated when they are followed by an infinitive. So, when there is an ellipsis of the non finite verb, both heads hosting TO and a preterite present are “functional”. Their syntactic structures are slighty identical: the structure corresponding to TO + V is,

and the structure corresponding to Pret.Pres. + V (note: ➳) is,

According to this structure, preterite present verbs seem to be raising verbs: the semantic subject of the non finite verb raises to Spec,TP to become the grammatical subject of the sentence, where Agree is visible between the subject and preterite present.

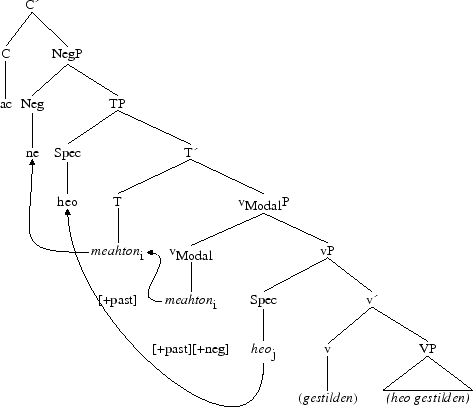

Let us go back to Examples (93) and (94) (now (98.a) and (99.a)) and illustrate them.

| willaž | žęt | gewrecan | gif | we | magon, | žeah | we | beotiaž | to | ∅. |

| want-IND.PRES | that-ACC | revenge | if | we | can-IND.PRES, | even if | we-NOM | threaten-IND.PRES | TO | ∅. |

and desire, if we can, to take revenge, and (if we are unable), we nevertheless threaten to do so. (coblick,

HomS_10_[BlHom_3]:127.446)

| žęt | heo | his | wedenheortnisse | gestilden, | ac | heo | ne | meahton | ∅. | |

| ... | that | he-NOM | his | madness | eased-SUBJ.PRET, | but | he-NOM | NEG | could-IND.PRET | ∅. |

... did all he could to assuage the madness of the unfortunate man, but could not prevail. (cobede,Bede_3:9. 184.32.1854)

Let us refine our analysis of preterite presents to stress their syntactic difference. We are going to look at:

examples displaying the structure MD + INF + OBJ-ACC,

| Męssepreost | sceal | habban | męsseboc | and | pistelboc, | and | sangboc | and | rędingboc | and | saltere | and | handboc | (...). |

| Priest-NOM | must-IND.PRES | have | book of mass-ACC | and | book of gospels-ACC, | and | book of chants-ACC | and | book of reading-ACC | and | psalms-ACC | and | handbook-ACC | (...). |

The priests must possess the book of prayers, the book of the Gospels, the book of chants as well as the book of psalms and the handbook.. (colwstan1,ĘLet_2_[Wulfstan_1]:157. 226)

| Hwylc | man | is | žęt | męge | ariman | ealle | ža | sar | & | ža | brocu | že | se | man | to | gesceapen | is? |

| What-NOM | man-NOM | is-IND.PRES | that | may-SUBJ.PRES | number | all-ACC | the-ACC | pain-ACC | & | the-ACC | diseases-ACC | that | the-NOM | man-NOM | to | destined-P.PASSE | is-IND.PRES? |

What man is he that may number all the pains and diseases that man is born to? (coblick,HomS_17_[BlHom_5]:55.99.795)

| foržon | že | heo | wolde | gehyran | his | word | & | his | lare. |

| for | that | she-NOM | would-PRET | hear | his | words-ACC | & | his | knowledge-ACC. |

for she would hear his words and his teaching. (coblick, HomS_21_[BlHom_6]:67.30.825)

| Hwęt, | hi | eac | witon | hwęr | hi | eafiscas | secan | žurfan, | ... |

| What, | they-NOM | thus | know-IND.PRES | where | they-NOM | river fish-ACC | seek | need-IND.PRES, | ... |

What, then they know where to find the fish they need, ... (cometboe,176.19.24.318)

examples displaying the structure MD + OBJ-ACC + INF,

| Tealde | & | wende | žęt | he | mid | swinglan | sceolde | ža | beldu | & | ža | anrednesse | his | heortan | anescian, | ša | he | mid | wordum | ne | mihte. |

| said-PRET | & | translated-PRET | that | he-NOM | with | whip-DAT | should-PRET | the-ACC | courage-ACC | & | the-ACC | perseverance-ACC | his | heart-GEN | weaken, | that | he-NOM | with | words-DAT | NEG | could-PRET. |

He said that he had to weaken the courage and perseverance of his heart by scourging himself, the which he could not do with words. (cobede,Bede_1:7. 36.32.307)

| ac | he | ma | wile | his | treowa | & | his | gehat | wiš | že | gehealdan... |

| but | he-NOM | no more | will-PRES | his | agreement-ACC | & | his | promise-ACC | with | you | hold... |

but he will not hold his promise towards you... (cobede,Bede_2:9. 130.24.1253)

| žęt | us | męg | ža | gyfe | syllan | ecre | eadignesse | & | eces | lifes | hęlo. |

| it-NOM | us | may-IND.PRES | the-ACC | gift-ACC | give | eternal-GEN | happiness-GEN | & | eternal-GEN | life-GEN | salvation-ACC. |

(it) can confer on us the gifts of life, of salvation, and of eternal happiness. (cobede,Bede_2:10.136.15.1320)

| Nu | nealęcež | žęt | we | sceolan | ure | ęhta | & | ure | węstmas | gesamnian. |

| Now | gets closer-IND.PRES | that | we-NOM | should-IND.PRES | our-ACC | gains-ACC | & | our-ACC | fruits-ACC | gather. |

The time is nigh at hand that we should gather together our substance and our gains. (coblick, HomS_14_[BlHom_4]:39.1.509)

| Sum | męg | ryne | tungla | secgan. |

| Some-NOM | can-IND.PRES | course-ACC | stars-ACC | tell. |

Some can fortell the course of the stars. (cochrist,21.671.453)

| ... | žęt | he | sceolde | boccręftas | & | gewrita | wisdomas | leornian. |

| ... | that | he-NOM | should-PRET | science-ACC | & | scriptures-GEN | knowledge-ACC | learn. |

... that he had to learn science and the knowledge of the scriptures. (cogregdC, GDPref_2_[C]:95.10.1078)

| Nę | męg | ic | ana | eower | gemang | acuman | & | eower | swarnyssa | & | eowre | saca. |

| No | may-IND.PRES | I-NOM | one | your-ACC | assembly-ACC | bear | & | your-ACC | heaviness-ACC | & | your-ACC | enemeis-ACC. |

I cannot bear either your assembly, your heaviness or your enemies any longer. (cootest,Deut:1.11.4454)

examples displaying the structure V + INF + OBJ-ACC,

| Ža | heht | heo | gesomnian | ealle | ža | gelęredestan | men | & | ža | leorneras: |

| Then | ordered-IND.PRET | he-NOM | gather | all-ACC | the-ACC | learned-ACC | men-ACC | & | the-ACC | disciples-ACC... |

by whom he was ordered, in the presence of many learned men... (cobede, Bede_4:25.344.20.3463)

| Brošor | mine, | nu | we | gehyrdon | secgan | ža | weoršunga | žyses | ondweardan | dęges... |

| Brother-NOM | my-NOM, | now | we-NOM | heard-IND.PRET | tell | the-ACC | celebration-ACC | this-GEN | present-GEN | day-GEN... |

My brother, we have now heard of the celebration of the present day... (coblick,HomS_47_[BlHom_12]:137.106.1661)

| & | het | sceawian | šęt | land | & | ša buruh | Iericho, | ... |

| & | wished-IND.PRET | look | this-ACC | country-ACC | & | the-ACC town-ACC | Jericho, | ... |

he wished to visit this country and the city of Jericho, ... (cootest,Josh:2.1.4382)

examples displaying the structure V + OBJ-ACC + INF,

| Ža | het | se | cyning | sona | neoman | žone | mete | & | ža | swęsendo... |

| Then | ordered-IND.PRET | the-NOM | king-NOM | soon | take | this-ACC | meat-ACC | & | this-ACC | food-ACC... |

he immediately ordered the meat set before him... (cobede, Bede_3:4.166.6.1591)

With these examples, we shall try and show that the syntax of lexical verbs and preterite presents when the object is case-marked accusative: vModal does not assign case, moreover, the object is semantically bound to a lexical V.

We then propose that in this kind of structures (with a preterite present verb), the object is semantically bound to the infinitive V (whatever its position: either between the preterite present and the infinitive or after the infinitive). It is indeed the object of the infinitive, as the subject is semantically bound to V before becoming the grammatical subject of the preterite present. Hence, we put forward the following hypothesis: in those structures, preterite presents are raising verbs as early as the OE period.

On the other hand, when there are two lexical verbs (one finite and another non finite), we are faced with two cases: either the object is bound to the finite verb (and it is the verb which assigns to the object), or it is bound to the non finite verb (and it is the subject of this verb).

Within the OE corpus, when we have looked through instances of pretereite presents and lexical verbs, more than two thirds of them dealt with preterite presents, as for the last third, we have mainly found the two lexical verbs hetan and habban.

These examples allow us to underline the syntax of the preterite present verbs and to validate the hypothesis of vModal (when the object is marked accusative, it semantically is the non finite verb“s). So, it seems that preterite presents syntactically behave in a different way to lexical verbs.

It is also to be noted that accusative-marked objects are the finite verbs semantic objects (unlike preterite presents which do not have objects, except a VP object).

Hence, we can infer that preterite presents are not lexical but semi-lexical verbs in OE since they assign no accusative case to any object. Furthermore, in early OE, preterite presents are raising verbs. These two statements allow us to claim that they are base-generated under the different syntactic position vModal.

We have just seen we could find two types of structures for preterite presents:

Pret.Pres + NP ou,

Pret.Pres + Infinitive (VP).

For the first case, the preterite present is a lexical verb as strong and weak are. For the second case, it is directly base-generated under vModal (when it is followed by an infiniitve) and the subject is base-generated under Spec,vP. We then proposed the functional head vModal to syntactically dominate V. For the OE period of language, preterite presents are not grammatical yet (and therefore cannot be base-generated under T). This is why we call them semi-lexical verbs.

The following examples (with WITAN and MUNAN in particular) give an illustration of the lexical status of preterite present verbs. Their syntax can either be Pref.Pres + NP or Pref.Pres + CP.

| ... | wite | žu | žęt | Apollonius | ariht | arędde | mynne | rędels? |

| ... | know-PRES | you-NOM | that | Apollonius-NOM | rightly | interpreted-PRET | my-ACC | riddle-ACC? |

... knowest thou that Apollonius hath rightly read my riddle? (coapollo,ApT:6.1.76)

| Ac | gemyne | žu | žęt | žu | žisne | ele, | že | ic | že | nu | sylle, | synd | in | ža | sę. |

| But | remember-IND.PRES | you-NOM | that | you-NOM | these-ACC | oils-ACC, | that | I-NOM | toi | always | give-PRES, | are-IND.PRES | to | the-ACC | sea-ACC. |

but do you remember to cast this oil I give you into the sea. (cobede,Bede_3:13.200.4.2025)

| wolde | žęt | he | in | žon | ongete, | žęt | žęt | mon | ne | węs, | se | že | him | ęteawde, | ... |

| voulut-PRET | que | il-NOM | ą travers | cela-INSTR | sūt-SUBJ.PRET, | que | cet-NOM | homme-NOM | NEG | était-IND.PRET, | celui-NOM | que | lui-DAT | révéla-PRET, | ... |

Grāce ą cela, il voulut qu“il sūt que cet homme n“était pas celui qui le révélāt, ... (cobede,Bede_2:9.130.16.1245)

| men | ne | cunnon | hwyder | helrunan | hwyrftum | scrižaš. |

| men-NOM | NEG | know-IND.PRES | where | hell-demons-NOM | turn-DAT | go-IND.PRES. |

men do not know where hell-demons direct their footsteps. (cobeowul,7.162. 127)

We have just defined two syntactic positions for preterite present verbs: V for lexical preterite presents and vModal for semi-lexical preterite presents.

Semi-lexical preterite present is then directly base-generated under vModal, and merges with T to satisfy its tense and φ features (with Spec,TP).

Let us take Example (33) (now (119.a)) again to underline what has just been said.

| ... | žęt | he | wiš | ęlfylcum | eželstolas | healdan | cuše, | ša | węs | Hygelac | dead. |

| ... | that | he-NOM | against | foreigners-DAT | native throne-ACC | hold | could-PRET, | since | was-IND.PRET | Hygelac-NOM | dead-NOM. |

... that he could hold his native throne against foreigners now that Hygelac was dead. (cobeowul,73.2367.1931)

The subject is assigned a θ-role by the infinitive, and the preterite present is then base-generated under vModal. For the derivation not to crash, the subject raises to Spec,TP to satisfy the EPP feature of T. Then, the preterite present satisfies its tense feature with T“s and its φ features with the subject“s under Spec,T. Once these features have been satisfied, the derivation can be spelled out.

Let us now go back to the functional head Neg. Examples (23) and (24) underlined the fact that cliticization of the negative adverbial particle ne onto preterite presents could exist, and that that particle always immediately preceded the finite verb. We shall see that this cliticization is not compulsory.

Like any other Germanic language, OE has this phenomenom of negative concord: if there are (more than) two negative elements in a single sentence, they do not cancel each other out but they conjointly express one and only one negation (see (29) ((29))).

| Siššan | of | žęre | tide | nęnig | Sceotta | cyninga | ne | dorste | wiš | Angelžeode | to | gefeohte | cuman | oš šysne | andweardan | dęg. |

| When | from | this-DAT | period-DAT | no | Scot-GEN | king-GEN | NEG | dared-PRET | against | Britain | to | fight-DAT | approach | till here-ACC | present-ACC | day-ACC. |

From that time, no king the Scots durst come into Britain to make war on the English to this day. (cobede,Bede_1:18.92.24.856)

| ... | no | šu | ymb | mines | ne | šearft | lices | feorme | leng | sorgian. |

| ... | no | you-NOM | about | me-GEN | NEG | needs-IND.PRES | body-GEN | comfort through food-DAT | longer | trouble. |

... no longer will you need trouble yourself to take care of my body. (cobeowul,16.448.374)

| foršam že | Apollonius | him | ondręt | žines | rices | męgna | swa žęt | he | ne | dear | nahwar | gewunian. |

| because | Apollonius-NOM | himself-DAT | dreads-IND.PRES | this-GEN | realm-GEN | power-ACC | so that | he-NOM | NEG | dares-IND.PRES | nowhere | live. |

for that Apollonius dreads the powers of the realm, so that he dares continue nowhere. (coapollo,ApT:7.17.108)

According to (24) ((24)), the Neg criterion determines the syntax of negative sentences: “all N-words carry a semantic-syntactic feature Neg and this feature is subject to a specific licensing condition”(note: ➳). Hence the introduction of a Neg Criterion: “a NEG operator must be in a spec-head configuration with a X0 [+NEG]; and an X0 [+NEG] must be in a spec-head configuration with a NEG operator” ((26) ((26)): 116). This criterion is insprired by Rizzi“s WH criterion.

Within the Minimalist framework, the spec-head relationship is not important but the way this relation is satisfied by local c-command is (minimal research within a minimal domain): “Apparent SPEC-H relations are in reality head-head relations involving minimal search (local c-command)” ((8) ((8)): 12).

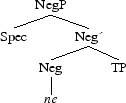

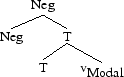

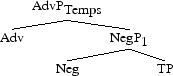

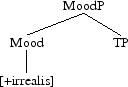

Let us go back to the negative adverbial particle ne. According to Zanuttini“s analysis in (25) ((25)), the negative particle ne is the head of the negative projection Neg, since it precedes the finite verb and another negative constituant is not needed for a sentence to be negative. What we question now is the position of this functional projection. Following Zanuttini, we propose the next position:

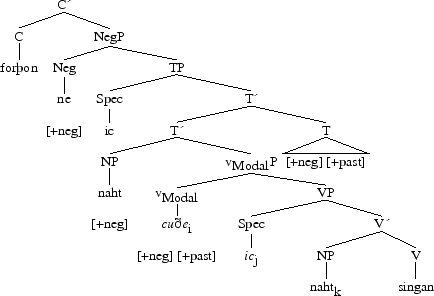

Let us now illustrate with Example (124) the position NegP.

| ac | he | ne | męg | for | scame | in | gan | buton | scrude. |

| but | he-NOM | NEG | can-IND.PRES | for | shame | in | go | without | clothing-DAT. |

but, for shame, he may not enter without clothing. (coapollo,ApT:14.15.267)

According to Chomsky“s Minimalist Program, all the constituants of a sentence are chosen within the lexicon fully marked, i.e. nouns or verbs bear the mark of singular, plural, gender, number, person, ...; they represent a set of features. So, for a derivation to be grammatical, each and every constituant must have its set of features satisfied by a (functional) category possessing the same features. Negation acts the same way: it is chosen at the same time as the finite verb and has an uninterpretable [+neg] feature which is satisfied by the functional head Neg having that same feature. While satisfying this feature, Neg merges with T.

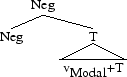

According to Halle and Marantz“s Distributed Morphology, we have the following steps:

Before the morphological fusion of T with vModal, we first have,

then after the morphological fusion of T with vModal,

and finally, after the morphological fusion of the head Neg with T+vModal, we have,

once these morphological fusions are done, there is Vocabulary Insertion.

At that point in our analysis, the OE sentence has a functional head Neg. In the corpus, very few examples displaying not have been found. When it is conjointly found with the negative adverbial particle ne, it is to be considered as a negative quantifier in the OE corpora ((52)) et ((67) ((67))), since it cannot be the only negation of the sentence at that period of time. Nevertheless, it is case-marked accusative (ACC) which turns it into a direct object of the infinitive verb.

| Ža | ondswared | he | žęt | he | noht | swylcra | cręfta | ne | cuše. |

| Alors | répondit-PRET | il-NOM | que | he-NOM | nothing-ACC | such-GEN | craft-GEN | NEG | knew-PRET. |

Then he answered that he did not know such a craft. (cobede,Bede_4:23.328. 8.3291)

| & | cwęš: | Ne | con | ic | noht | singan. |

| & | said-PRES: | NEG | know-IND.PRES | I-NOM | nothing-ACC | sing. |

and he said: I do not know how to sing. (cobede,Bede_4:25.342.29.3445)

| ... | foržon | ic | naht | singan | ne | cuše. |

| ... | for | I-NOM | nothing-ACC | sing | NEG | knew-PRET. |

... because I did know any song to sing. (cobede,Bede_4:25.342.29.3446)

In these specific cases, the Neg criterion applies: there is a relationship between Neg and the negative N.

Let us give an illustration of Example (130):

the Neg criterion takes place without T blocking the local c-command relation between the head Neg, ne and Q, naht. Then, at the morphological level, there is Merger of Neg with T (to get the linear order ne).

Within one single sentence, OE can have several negative elements expressing one and only one negation. Ne can then be associated with negative adverbs. Following (12) ((12)), could we assume these adverbs to be Specs of functional heads? Our hypothesis is that a functional head corresponds to each type of adverb. Let us study some examples.

| foršam že | Apollonius | him | ondręt | žines | rices | męgna | swa žęt | he | ne | dear | nahwar | gewunian. |

| because | Apollonius-NOM | himself-DAT | dreads-IND.PRES | the-GEN | realm-GEN | power-ACC | so that | he-NOM | NEG | dares-IND.PRES | nowhere | live. |

for that Apollonius dreads the powers of the realm, so that he dares continue nowhere. (coapollo,ApT:7.17.108)

| Ond | he | žes | biscop | ricum | monnum | no | for | are | ne | for | ege | nęfre | forswigian | nolde, | ... |

| And | he-NOM | the-NOM | bishop-NOM | powerful-DAT | men-DAT | nor | because of | prosperity | nor | because of | fear | never | conceal | NEG wanted-PRET, | ... |

He never gave money to the powerful men of the world (...) if he happened to entertain them, ... (cobede,Bede_3:3.162.12.1557)

Examples (133) and (134) underline the use of both ne and a negative adverb (which are base-generated in situ). As for Example (135), the only negation of the sentence is a negative adverb.

| Na | žu | minne | šearft | hafalan | hydan... |

| No | you-NOM | my-ACC | need-IND.PRES | head-ACC | hide... |

You will not need to hide my head... (cobeowul,16.445.368)

We have mentioned that the Neg criterion implies a head-to-head relation, so all the different negative adverbs are to be heads for the Neg criterion to apply.

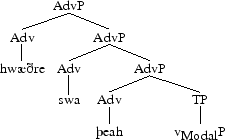

Thus, the place adverb nahwar of Example (133) and the time adverb of Example (134) are both under an Adv head. The head Neg then c-commmands these two adverbs (under respectively AdvPPlace and AdvPTime); Example (135) is the most interesting one: if the adverb is the only negation in the sentence, what is its position? We propose it is generated under a position which differs from the ones precedingly described. It cannot be Spec,CP since no subject-verg inversion can be seen (which is the case in sentences where the first element is either a negative constituant or the adverbs ža/žonne (see (69) ((69)) and (49) ((49)))).

It cannot be Neg1, otherwise the adverb would immediately precede the finite verb. Then there exists a position above TP where this type of (time) adverb is base-generated. We assume it is a head different from Neg so that the Neg criterion will apply.

Let us take Example (135) (now (137.a)) again and give its syntactic structure.

| Na | žu | minne | žearft | hafalan | hydan. |

| No | you-NOM | my-ACC | need-IND.PRES | head-ACC | head... |

You will not need ti hide my head... (cobeowul,16.445.368)

Under Neg, one can notice an empty element: even if ne is not realized, the Neg criterion indeed takes place.

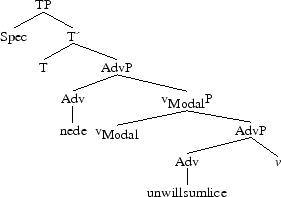

Now, let us try and see if there are as many functional heads in OE as in CE (according to Cinque“s classification), but we assume adverbs to be base-generated under functional heads corresponding to each type of adverb but not under Specs. To achieve that, we have selected examples that appear to be relevant for our analysis, i.e. examples where there are several adverbs in the same sentence, so that we can see if such a classification exists in OE.

| Nęnig | heora | žohte | žęt | he | žanon | scolde | eft | eardlufan | ęfre | gesecean... |

| No | them-GEN | thought-PRET | that | he-NOM | from there | should-PRET | often | dear home-ACC | never | seek... |

None of them thought that he would ever again seek from there his dear home... (cobeowul,23.691.582)

| sceolde | hwęšre | swa | žeah | ęšeling | unwrecen | ealdres | linnan. |

| should-PRET | if | so | yat | prince-NOM | unavenged-NOM | elder-GEN | lose. |

yet it had happened that a prince had to lose life unavenged. (cobeowul,76.2441. 1992)

| žonne | wolde | heo | ealra | nyhst | hy | bažian | & | žwean. |

| then | wanted-PRET | she-NOM | all-GEN | at last | them-ACC | bath | & | wash. |

She finally wanted to bathe and wash them all. (cobede,Bede_4:21. 318.18.3198)

| se | sceal | nede | in | helle | duru | unwillsumlice | genižerad | geladed | beon... |

| he-NOM | shall-IND.PRES | necessarily | in | hell-GEN | gate-ACC | unwillingly | damned-P.PASSE-NOM | led-P.PASSE | be... |

he will certainly be damned, and enter the gate of hell whether he will or no... (cobede,Bede_5:15.442.21.4451)

| No | he | wiht | fram | me | flodyžum | feor | fleotan | mihte... |

| No | he-NOM | nought | fra from | me-DAT | flood-waves-DAT | far | swim | could-PRET... |

He could not swim at all far from me in the flood-waves... (cobeowul,18.541.460)

| ne | męg | ic | her | leng | wesan. |

| NEG | can-IND.PRES | I-NOM | here | any longer | stay. |

I cannot stay here any longer. (cobeowul,86.2799.2283)

| Nales | žęt | sona | žęt | innstępe | & | ungežeahtenlice | žęm | gerynum | onfon | wolde | žęs | Cristenan | geleafan... |

| None | that | immediately | this-ACC | directly | & | rapidly | the-DAT | sacrements-DAT | receive | wanted-PRET | the-GEN | christian-GEN | beliefs-GEN... |

he would not immediately and unadvisedly embrace the mysteries of the Christian faith... (cobede,Bede_2:8.124.13.1180)

| Šęt | hwęšre | ęšelice | ongetan | meahton | ealle | ža | žęt | cušon. |

| This-ACC | yet | all | understand | could-IND.PRET | all-NOM | that-NOM | that | knew-IND.PRET. |

Yet, they could all understand what they had the knowledge of. (cobede,Bede_4:26.348.29.3518)

| ... | žęt | he | šęr | eac | swylce | bebyrged | beon | moste... |

| ... | that | he-NOM | there | also | thus | buried-P.PASSE | be | should-PRET... |

... that he might also be buried in the same place...... (cobede,Bede_4:30.374.1.3735)

| Hwider | męg | ic | nu | faran? |

| Wher | can-IND.PRES | I-NOM | now | go? |

Where can I go now? (coapollo,ApT:12.9.198)

| Hat | him | findan | hwar | he | hine | męge | wuršlicost | gerestan. |

| Bid-IMP | him | find | where | he-NOM | him-ACC | may-SUBJ.PRES | honourably | rest. |

bid that there be found for him where he may rest most honourably. (coapollo,ApT:17.27.365)

In Examples (149), (151), (153) and (155), adverbs have the following syntactic positions:

| Nęnig | heora | žohte | žęt | he | žanon | scolde | eft | eardlufan | ęfre | gesecean... |

| No | them-GEN | thought-PRET | that | he-NOM | from there | should-PRET | often | dear home-ACC | never | seek... |

None of them thought that he would ever again seek from there his dear home... (cobeowul,23.691.582)

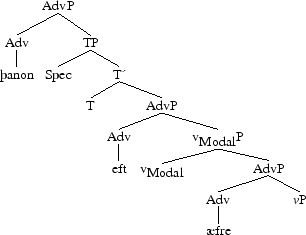

which has the following structure,

| sceolde | hwęšre | swa | žeah | ęšeling | unwrecen | ealdres | linnan. |

| should-PRET | if | so | yat | prince-NOM | unavenged-NOM | elder-GEN | lose. |

yet it had happened that a prince had to lose life unavenged. (cobeowul,76.2441. 1992)

which has the following structure,

| žonne | wolde | heo | ealra | nyhst | hy | bažian | & | žwean. |

| then | wanted-PRET | she-NOM | all-GEN | at last | them-ACC | bath | & | wash. |

She finally wanted to bathe and wash them all. (cobede,Bede_4:21.318. 18.3198)

which has the following structure,

| se | sceal | nede | in | helle | duru | unwillsumlice | genižerad | geladed | beon. |

| he-NOM | shall-IND.PRES | necessarily | in | hell-GEN | gate-ACC | unwillingly | damned-P.PASSE-NOM | led-P.PASSE | be... |

he will certainly be damned, and enter the gate of hell whether he will or no...

Lui, que l“on a involontairement condamné aux portes de l“enfer, doit nécessairement źtre disculpé. (cobede,Bede_5:15.442.21.4451)

whose structure is,

Let us first have a look at these four examples. In Example (150), the adverbs oft et ęfre are under two functional heads (if we follow Cinque“s analysis and hierarchy: 106) AspFrequentative and AspPerfective. We then have a first structure:

[T [oft AspFrequentative [vModal [ęfre AspPerfective]]]]

In Example (156), nede and unwillsumlice also are under functional heads. These are relevant for our analysis since ModNecessity and ModVolition are modal heads. We then have the second structure,

[T [nede ModNecessity [vModal [(un)willsumlice ModVolition]]]]

For Cinque, Mod functional heads are hierarchically higher than Asp heads. And if we sum up our remarks, we have the following hierarchy:

[T [nede ModNecessity [oft AspFrequentative [ [(un)willsumlice ModVolition [ęfre AspPerfective]]]]]]

In the preceding structure, we have only taken into account Mod and Asp heads. Let us now be more accurate by adding the functional heads corresponding to the other adverbs we mentioned in Examples (150) to (156).

[žonne AdvTime [C [žanon AdvPlace [hwęšre [swa [žeah [T [nede ModNecessity [oft AspFrequentative [ [(un)willsumlice ModVolition [ęfre AspPerfective [nyhst]]]]]]]]]]]]].

Yet, these few examples only demonstrate the use of a small number of adverbs. Here is a classification of adverbs we have found when used along preterite present verbs, keeping in mind that an adverb can have different meanings and then belong to different categories. Our reference texts are still Beowulf, Cura Pastoralis and Apollonius of Tyre. We are using Cinque“s method to classify them.

Time adverbs : a “always”, ęfre/nęfre “ever, never”, ęrest “first”, ęror “before”, eac “since”, emb “before, after”, fyrmest “first”, geara “well, rapidly, near”, gen “already, now, still”, get “already, still”, iu “precedingly”, leng “long”, nu “now”, oft “often”, sel/selust “soon”, seldon “rarely”, somed “simultaneously”, sona “soon”, symble “always”, syššan “since, now, then”, toweardlice “towards”, ža/ žonne “then”, žonne “already” ;

Place adverbs : ęr “soon, already”, emb “near”, fyrr/feorr “far”, furšur “further”, hider “hither”, nahwar “nowhere”, žęr “where”, uute/utan “out”, wide “wide” ;

modality adverbs : aninga “necessarily”, eaš “willingly”, lustlice “willingly”, nede “necessarily”, (un)willsumlice “willingly”,

manner adverbs : aešmodlice “humbly, kindly”, eaš “lightly”, aninga “rapidly”, fęstlice “constantly, strictly”, fremsumlice “kindly”, freolslice “freely”, fullice “perfectly, fully”, furšum “exactly, already”, fyrmest “specially”, gearwe “well, fully”, geornlicor “cautiously”, hergendlice “praiseworthily”, hrędlicor “suddenly”, hu “how”, hwęšre “whether, alreday”, lišelice “slowly, lightly”, lustlice “happily”, smealice “precisely, subtly”, somed “together”, sweotole/sweotollice “clearly, precisely”, žonne “then, already”, uneašelice “with difficulty”, wel “well, fully”.

Other types of adverbs : eac “also”, fordon “thus, because”, hrędlicor “suddenly”, hwędre “yet, already”, no “no, never”, swa “so, consequently”, žonne “thus, already”.

Let us go back to (12) ((12)): 106 and see if we can apply it to OE adverbs.

| [franklyMoodSpeech Act | |

| fortunatelyMoodEvaluative | |

| allegedlyMoodEvidential | sweotole/sweotollice, fullice, gewislicost, |

| gerisenlice, huru, openlicor, hluttorlice, | |

| rihtlice, smealice | |

| probablyModEpistemic | |

| onceT(Past) | eft, nu, iu, eac |

| thenT(Future) | ža/žonne, nu, teowardlice |

| perhapsMoodIrrealis | |

| necessarilyModNecessity | nede, aninga |

| possiblyModPossibility | |

| willinglyModVolitional | eaš, lustlice |

| inevitablyModObligation | swa |

| cleverly, diligentlyModAbility/Permission | |

| usuallyAspHabitual | hioweslice |

| againAspRepetitive(I) | eft, gelomlice |

| oftenAspFrequentative(I) | eft, gelomlice |

| quicklyAspCelerative(I) | aninga |

| alreadyT(Anterior) | eac, emb, iu, syššan |

| no longerAspTerminative | |

| stillAspContinuative | get, gen, swa |

| alwaysAspPerfect | a/(n)ęfre, simble |

| just, recentlyAspRetrospective | ęr |

| soon, suddenly, immediatelyAspProximative | sona, sel/selust, hrędlicor |

| briefly, long timeAspDurative | leng |

| characteristicallyAspGeneric/Progressive | |

| almostAspProspective | neah |

| completelyAspSg.Completive(I) | fullice |

| tuttoAspPl.Completive | |

| wellVoice | wel, sel/selust, geara |

| fast/earlyAspCelerative(II) | aninga, geara |

| completelyAspSg.Completive(II) | fullice |

| againAspRepetitive(II) | eft, gelomlice |

| oftenAspFrequentative(II) | eft, gelomlice] |

We have to admit that OE does not seem to have as many functional heads as CE has, even if some adverbs do not enter this hierarchy.

Hence the followong functional heads:

[sweotole/sweotollice clearly, precisely, fullice perfectly, fully, gewislicost certainly, surely, gerisenlice honorably, conveniently, huru yet, certainly, openlicor obviously, hluttorlice sincerely, clearly, rihtlice right, well, smealice precisely, subtly MoodEvidential [eft again, nu now, iu precedingly, eac since T(Past) [ža/žonne then, nu now, teowardlice towards T(Future) [nede necessarily, aninga willingly ModNecessity [eaš willingly, lustlice willingly ModVolitional [swa thus, consequently ModObligation [hioweslice? informally AspHabitual [eft again, gelomlice frequently AspRepetitive(I) [eft again, gelomlice frequently AspFrequentative(I) [aninga rapidly AspCelerative(I) [emb before, after, iu precedingly, syššan since, now, then, eac? since T(Anterior) [get yet, again, gen already, now, again, swa thus, consequently AspContinuative [a/(n)ęfre never, always, simble always, constantly AspPerfect[ęr before, once AspRetros- pective [sona soon, sel/selust soon, hrędlicor suddenly AspProximative [leng long AspDurative [neah near, almost AspProspective [fullice perfectly, completely AspSg.Completive(I) [wel well, sel/selust soon, geara formerly, once Voice [aninga rapidly, geara formerly, once AspCelerative(II) [fullice perfectly, completely AspSg.Completive(II) [eft again, gelomlice frequently AspRepetitive(II) [eft again, gelomlice frequently AspFrequentative(II)]]...

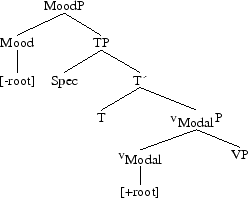

In Section 2.8.2, some of the heads we have listed will help us in our analysis, specially Mod(ality) heads. In Section 2.8.1, we shall show the existence of the functional head MoodIrrealis (even if it does not appear in the preceding hierarchy).

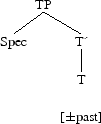

In OE, there are two tenses: present and past. Within the Minimaliste theory, these two tenses have the form of formal features possessed by T.

These features are satisfied by the same features a verb has, as shown in the following example,

| Hwider | męg | ic | nu | faran? |

| Where | can-IND.PRES | I-NOM | now | go? |

Where can I go now? (coapollo,ApT:12.9.198)

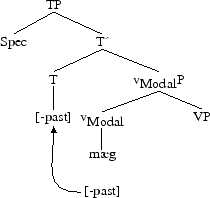

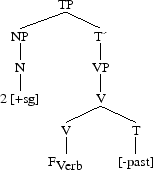

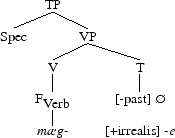

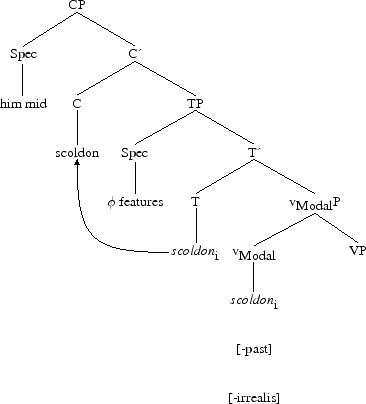

In this example, we know męg is a present form because of its morphology, i.e. its root vowel ę (to be opposed to i for a past form). Then, this verb has a [-past] feature when chosen into the lexicon, as well as a [+modal] feature inherent to preterite present verbs. The [+modal] feature is satisfied by a v having the same feature, i.e. vModal; as for the [-past] feature, it is satisfied by T. We then have:

MAGAN : root vowel /-ę/, ending ∅, marks of present sg 1 et 3 (in the plural, root vowel /-a/ and ending /-on/)

vModal = [+modal], [-past]

T = [-past]

which gives the following structure (even if we are dealing with Distributed Morphology, we think it makes our analysis clearer to use structures):

or, accordin to DM,

[T-V-Agr-sg2] ⟷ męg [modal, present, sg2]

This form is then inserted into the sentence.

At this stage of the computation, męg still has a [-past] feature which must be satisfied by T. Once this feature is satisfied, it is erased. But we can add the [-irrealis] feature to the [-past] feature. We then assume the existence of the functional head Mood for subjunctive forms, as well as the fact that the [-irrealis] mood is to be found under T for indicative forms.

Let us now take an example where Agree is visible.

| Gif | šu | wilt | mine | ęšelborennesse | witan... |

| If | you-NOM | want-IND.PRES. | my-ACC | noblility-ACC | know... |

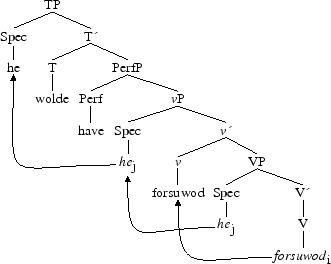

If thou wilt know my nobility... (coapollo,ApT:15.17.298)

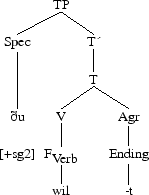

At the level of the morphological component, WILLAN is structured as follows,

Now, if the φ features of the verb are satisfied with Spec,T, we obtain,

The morphology of past forms will enable us to identify them.