H. Khalil

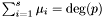

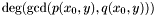

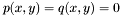

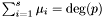

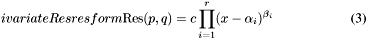

This section describes an algorithm, which uses generalized eigenvalues and eigenvectors, for solving a system of two bivariate polynomials  , with

, with ![$p, q \in \mathbb{R} [x, y]$](form_229.png) . It treats multiple roots, which are usually considered as obstacles for numerical linear algebra techniques. The numerical difficulties are handled with the help of singular value decomposition (SVD) of the matrix of eigenvectors associated to each eigenvalue. The extension to

. It treats multiple roots, which are usually considered as obstacles for numerical linear algebra techniques. The numerical difficulties are handled with the help of singular value decomposition (SVD) of the matrix of eigenvectors associated to each eigenvalue. The extension to  equations could be treated similarly.

equations could be treated similarly.

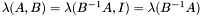

Let  be two square matrices of size

be two square matrices of size  . A {generalized eigenvalue} of

. A {generalized eigenvalue} of  and

and  is a value in the set

is a value in the set

![\[ \lambda (A, B) : =\{\lambda \in \mathbb{C} ; \det (A - \lambda B) = 0\}. \]](form_231.png)

A vector  is called a {generalized eigenvector} associated to the eigenvalue

is called a {generalized eigenvector} associated to the eigenvalue  if

if  . The matrices

. The matrices  and

and  have

have  generalized eigenvalues if and only if

generalized eigenvalues if and only if  . If

. If  , then

, then  can be finite, empty, or infinite. Note that if

can be finite, empty, or infinite. Note that if  then

then  . Moreover, if

. Moreover, if  is invertible then

is invertible then  , which is the ordinary spectrum of

, which is the ordinary spectrum of  .\

.\

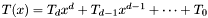

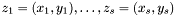

Recall that an  matrix

matrix  with polynomial coefficients can be equivalently written as a polynomial with

with polynomial coefficients can be equivalently written as a polynomial with  matrix coefficients. If

matrix coefficients. If  , we obtain

, we obtain  , where

, where  are

are  matrices.

matrices.

And we have the following interesting property :

|

Proposition: With the above notation, the following equivalence holds:

![\[ \hspace{1em} T^t (x) v = 0 \Leftrightarrow (A - xB) \left( \begin{array}{c} v\\ xv\\ \vdots\\ x^{d - 1} v \end{array} \right) = 0. \]](form_247.png)

|

From now on we will assume that  is an algebraically closed field and suppose given two bivariate polynomials

is an algebraically closed field and suppose given two bivariate polynomials  and

and  in

in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, y]$](form_250.png) . Our aim will be to study and compute their common roots. This problem can be interpreted more geometrically. Polynomials

. Our aim will be to study and compute their common roots. This problem can be interpreted more geometrically. Polynomials  and

and  actually define two algebraic curves in the affine plane

actually define two algebraic curves in the affine plane  (having coordinates

(having coordinates  ) and we would like to know their intersection points.

) and we would like to know their intersection points.

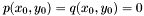

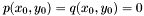

Hereafter we will consider systems  having only a {finite} number of roots. This condition is not quite restrictive since it is sufficient (and necessary) to require that polynomials

having only a {finite} number of roots. This condition is not quite restrictive since it is sufficient (and necessary) to require that polynomials  and

and  are coprime in

are coprime in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, y]$](form_250.png) (otherwise one can divide them by their

(otherwise one can divide them by their  ).

).

In the case where one of the curve is a line, i.e. one of the polynomial has degree 1, the problem is reduced to solving a univariate polynomial. Indeed, one may assume e.g. that  and thus we are looking for the roots of

and thus we are looking for the roots of  . Let us denote them by

. Let us denote them by  . Then we know that

. Then we know that

![\[ p (x, 0) = c (x - z_1)^{\mu_1} (x - z_2)^{\mu_2} \cdots (x - z_s)^{\mu_s}, \]](form_257.png)

where the  's are assumed to be distinct and

's are assumed to be distinct and  is a non-zero constant in

is a non-zero constant in  . The integer

. The integer  , for all

, for all  , is called the {multiplicity} of the root

, is called the {multiplicity} of the root  , and it turns out that

, and it turns out that  if

if  do not vanish at infinity in the direction of the

do not vanish at infinity in the direction of the  -axis (in other words, if the homogeneous part of

-axis (in other words, if the homogeneous part of  of highest degree do not vanish when

of highest degree do not vanish when  ). This later condition can be avoid in the projective setting: let

). This later condition can be avoid in the projective setting: let  be the homogeneous polynomial obtained by homogenizing

be the homogeneous polynomial obtained by homogenizing  with the new variable

with the new variable  , then we have

, then we have

![\[ p (x, 0, t) = c (x - z_1 t)^{\mu_1} (x - z_2 t)^{\mu_2} \cdots (x - z_s t)^{\mu_s} t^{\mu_{\infty}}, \]](form_267.png)

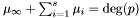

where  is an integer corresponding to the multiplicity of the root at infinity, and

is an integer corresponding to the multiplicity of the root at infinity, and  . Moreover, it turns out that the roots

. Moreover, it turns out that the roots  and their corresponding multiplicities can be computed by eigenvalues and eigenvectors computation.

and their corresponding multiplicities can be computed by eigenvalues and eigenvectors computation.

In the sequel we will generalize this approach to the case where  and

and  are bivariate polynomials of arbitrary degree. For this we first need to recall the notion of multiplicity in this context. Then we will show how to recover the roots from multiplication maps.

are bivariate polynomials of arbitrary degree. For this we first need to recall the notion of multiplicity in this context. Then we will show how to recover the roots from multiplication maps.

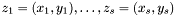

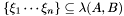

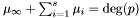

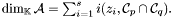

Let  be two coprime polynomials in

be two coprime polynomials in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, y]$](form_250.png) ,

,  and

and  the corresponding algebraic plane curves,

the corresponding algebraic plane curves,  the ideal they generate in

the ideal they generate in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, y]$](form_250.png) and

and ![$\mathcal{A} : = \mathbbm{K} [x, y] / I$](form_274.png) the associated quotient ring. We denote by

the associated quotient ring. We denote by  the distinct intersection points in

the distinct intersection points in  of

of  and

and  (i.e. the distinct roots of the system

(i.e. the distinct roots of the system  ).

).

A modern definition of the intersection multiplicity of  and

and  at a point

at a point  is (see [Ful84])

is (see [Ful84])

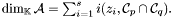

![\[ i (z_i, \mathcal{C}_p \cap \mathcal{C}_q) : = \dim_{\mathbbm{K}} \mathcal{A}_{z_i} < \infty, \]](form_277.png)

where the point  is here abusively (but usually) identified with its corresponding prime ideal in

is here abusively (but usually) identified with its corresponding prime ideal in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, y]$](form_250.png) ,

,  denoting the ordinary localization of the ring

denoting the ordinary localization of the ring  by this prime ideal. As a result, the finite

by this prime ideal. As a result, the finite  -algebra

-algebra  (which is actually finite if and only if

(which is actually finite if and only if  and

and  are coprime in

are coprime in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, y]$](form_250.png) ) can be decomposed as the direct sum

) can be decomposed as the direct sum

![\[ \mathcal{A} = \mathcal{A}_{z_1} \oplus \mathcal{A}_{z_2} \oplus \cdots \oplus \mathcal{A}_{z_s} \]](form_281.png)

and consequently

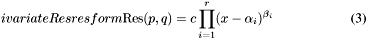

The intersection multiplicities can be computed using a resultant. The main idea is to project ``algebraically'' the intersection points on the  -axis. To do this let us see both polynomials

-axis. To do this let us see both polynomials  and

and  in

in ![$A [y]$](form_283.png) where

where ![$A : = \mathbbm{K} [x]$](form_284.png) , that is to say as univariate polynomials in

, that is to say as univariate polynomials in  with coefficients in the ring

with coefficients in the ring  which is a domain; we can rewrite

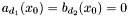

which is a domain; we can rewrite

![\begin{equation} \label{A[x]} p (x, y) = \sum_{i = 0}^{d_1} a_i (x) y^i, \hspace{.2cm} q (x, y) = \sum_{i = 0}^{d_2} b_i (x) y^i . \end{equation}](form_285.png)

Their resultant (with respect to  ) is an element in

) is an element in  which is non-zero, since

which is non-zero, since  and

and  are assumed to be coprime in

are assumed to be coprime in ![$A [y]$](form_283.png) , and which can be factorized, assuming that

, and which can be factorized, assuming that  and

and  do not vanish simultaneously, as

do not vanish simultaneously, as

where the  's are distinct elements in

's are distinct elements in  and

and  (as sets). For instance, if all the

(as sets). For instance, if all the  are distinct then we have

are distinct then we have  and

and  for all

for all  . Moreover, we have (see e.g. [Ful84] (S)):

. Moreover, we have (see e.g. [Ful84] (S)):

Proposition: For all  , the integer , the integer  equals the sum of all the intersection multiplicity of equals the sum of all the intersection multiplicity of  and and  at the points at the points  such that such that  . . |

As a corollary, if all the  's are distinct (this can be easily obtained by a linear change of coordinates

's are distinct (this can be easily obtained by a linear change of coordinates  ) then

) then  is nothing but the valuation of

is nothing but the valuation of  at

at  . Another corollary of this result is the well-know Bezout theorem for algebraic plane curves, which is better stated in the projective context. Let us denote by

. Another corollary of this result is the well-know Bezout theorem for algebraic plane curves, which is better stated in the projective context. Let us denote by  and

and  the homogeneous polynomials in

the homogeneous polynomials in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, y, t]$](form_302.png) obtained from

obtained from  and

and  by homogenization with the new variable

by homogenization with the new variable  .

.

Proposition: [Bezout theorem] If  and and  are coprime then the algebraic projective plane curves associated to are coprime then the algebraic projective plane curves associated to  and and  intersect in intersect in  points in points in  , counted with multiplicities. , counted with multiplicities. |

{proof} It follows straightforwardly from the previous proposition and the well-known fact that  is a homogeneous polynomial in

is a homogeneous polynomial in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, t]$](form_306.png) of degree

of degree  (see e.g. [Lang02], [VWe48II]). {proof}

(see e.g. [Lang02], [VWe48II]). {proof}

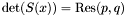

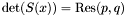

We take again the notation of A[x]} and [*] . We denote by  the Sylvester matrix of

the Sylvester matrix of  and

and  seen in

seen in ![$A [y]$](form_283.png) (assuming that both as degree at least one in

(assuming that both as degree at least one in  ); thus

); thus  . From [*] , we deduce immediately that

. From [*] , we deduce immediately that  vanishes at a point

vanishes at a point  if and only if either there exists

if and only if either there exists  such that

such that  , or either

, or either  (in which case the intersection point is at infinity). Therefore one may ask the following question : being given a point

(in which case the intersection point is at infinity). Therefore one may ask the following question : being given a point  such that

such that  , how to recover all the possible point

, how to recover all the possible point  such that

such that  ?

?

Suppose given such a point  and assume that

and assume that  and

and  are not both zero. If

are not both zero. If  is of dimension one, then it is easy to check that there is only one point

is of dimension one, then it is easy to check that there is only one point  such that

such that  and moreover any element in

and moreover any element in  is a multiple of the vector

is a multiple of the vector ![$[1, y_0, \cdots, y_0^{d_1 + d_2 - 1}]$](form_319.png) . Therefore to compute

. Therefore to compute  , we only need to compute a basis of

, we only need to compute a basis of  and compute the quotient of its second coordinate by its first one. In case of multiple roots, this construction can be generalized as follows:

and compute the quotient of its second coordinate by its first one. In case of multiple roots, this construction can be generalized as follows:

Proposition: Let  be any basis of the kernel be any basis of the kernel  , ,  be the matrix whose be the matrix whose  row is the vector row is the vector  , ,  be the be the  -submatrix of -submatrix of  corresponding to the first corresponding to the first  columns and columns and  be the be the  -submatrix of -submatrix of  corresponding to the columns number corresponding to the columns number  . Then . Then  is the set of roots of the equations is the set of roots of the equations  (i.e. the set of (i.e. the set of  -coordinates of the intersection points of -coordinates of the intersection points of  and and  above above  . . |

In this theorem, observe that the construction of  and

and  is always possible because we assumed that both polynomials

is always possible because we assumed that both polynomials  and

and  depend on the variable

depend on the variable  , which implies that the number of rows in the matrix

, which implies that the number of rows in the matrix  is always strictly greater than the

is always strictly greater than the  .

.

The previous theorem shows how to recover the  -coordinates of the roots of the system

-coordinates of the roots of the system  from the Sylvester matrix. However, instead of the Sylvester matrix we can use the Bezout matrix to compute

from the Sylvester matrix. However, instead of the Sylvester matrix we can use the Bezout matrix to compute ![$\tmop{Res} (p, q) \in A [x]$](form_336.png) (see section [*] ). This matrix have all the required properties to replace the Sylvester matrix in all the previous results, except in proposition [*] . Indeed, the Bezout matrix being smaller than the Sylvester matrix, the condition given in remark [*] is not always fulfilled; using Bezout matrix in proposition [*] requires that for all roots

(see section [*] ). This matrix have all the required properties to replace the Sylvester matrix in all the previous results, except in proposition [*] . Indeed, the Bezout matrix being smaller than the Sylvester matrix, the condition given in remark [*] is not always fulfilled; using Bezout matrix in proposition [*] requires that for all roots  of

of  ,

,

![\[ \max (\deg (p (x_0, y), \deg (q (x_0, y)) > \deg (\gcd (p (x_0, y), q (x_0, y)) . \]](form_337.png)

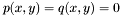

This condition may failed: take for instance  in the system

in the system

![\[ \left\{ \begin{array}{l} p (x, y) = x^2 y^2 - 2 y^2 + xy - y + x + 1\\ q (x, y) = y + xy \end{array} \right. \]](form_339.png)

Note that the use of the Bezout matrix gives, in practice, a faster method because it is a smaller matrix than the Sylvester matrix, even if its computation takes more time (the save in the eigen-computations is greater).

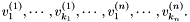

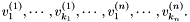

We are now ready to describe our resultant-based solver. According to proposition [*] , we replace the computation of the resultant, its zeroes, and the kernel of  (or the Bezout matrix) for each root

(or the Bezout matrix) for each root  by the computation of generalized eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the associated companion matrices

by the computation of generalized eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the associated companion matrices  and

and  . This computation can be achieved with the QZ algorithm [GLVL96]. Here are some numerical problems which might occur: {enumeratealpha}

. This computation can be achieved with the QZ algorithm [GLVL96]. Here are some numerical problems which might occur: {enumeratealpha}

- In order to compute the

-coordinates of intersection points, it is necessary to compute the real generalized eigenvalues of

-coordinates of intersection points, it is necessary to compute the real generalized eigenvalues of  . Numerically, some of these values can contain a nonzero imaginary part. Generally such a problem is encountered for multiple eigenvalues.

. Numerically, some of these values can contain a nonzero imaginary part. Generally such a problem is encountered for multiple eigenvalues.

- What does it mean by a numerical multiple

-coordinate?

-coordinate?

- How do we choose the linearly independent vectors among the computed eigenvectors? {enumeratealpha} For difficulty ``a'' we choose

, and any eigenvalue whose imaginary part is of absolute value less than

, and any eigenvalue whose imaginary part is of absolute value less than  will be considered real.

will be considered real.

For difficulty ``b'', we choose possibly a different  and gather the points which lay in an interval of size

and gather the points which lay in an interval of size  . According to the following proposition, the algorithm remains effective.

. According to the following proposition, the algorithm remains effective.

Proposition: Assume that  with corresponding generalized eigenvectors with corresponding generalized eigenvectors   with with  . We define . We define  the matrix whose its rows are the matrix whose its rows are  Then, if Then, if  is the first left is the first left  block of block of  and and  the second the second  block, then the generalized eigenvalues of block, then the generalized eigenvalues of  and and  give the set of ordinates of the intersections above give the set of ordinates of the intersections above  ; i.e. this algorithm can be used to gather clusters of ; i.e. this algorithm can be used to gather clusters of  -coordinates and regarding them as the projection of only one point. -coordinates and regarding them as the projection of only one point. |

For difficulties ``c'', it is necessary to use the singular value decomposition: If  a generalized eigenvalue of

a generalized eigenvalue of  and

and  , and

, and  the matrix of the associated eigenvectors, then the singular value decomposition of

the matrix of the associated eigenvectors, then the singular value decomposition of  is

is

![\[ E = U \Sigma V^t, \tmop{with} \Sigma = \left( \begin{array}{cccccc} \sigma_1 & & & & & \\ & \ddots & & & & \\ & & \sigma_r & & & \\ & & & 0 & & \\ & & & & \ddots & \\ & & & & & 0 \end{array} \right) \hspace{1em} \]](form_351.png)

and  is the rank of

is the rank of  . Let

. Let

![\[ E' = E \cdot V = U \cdot \Sigma = [\sigma_1 u_1 \cdots \sigma_r u_r \hspace{0.25em} 0 \cdots 0] = [e'_1 \cdots e'_r \hspace{0.25em} 0 \cdots 0] . \]](form_352.png)

The matrix  is also a matrix of eigenvectors, because the changes are done on the columns, and V is invertible. Hence

is also a matrix of eigenvectors, because the changes are done on the columns, and V is invertible. Hence  and

and  have the same rank

have the same rank  , and

, and ![$E'' = [e'_1 \cdots e'_r]$](form_354.png) is a matrix of linearly independent eigenvectors. Consequently

is a matrix of linearly independent eigenvectors. Consequently  can be used to build

can be used to build  and

and  .

.

This leads to the following complete algorithm:

{Algorithm { {Numerical approximation of the root of a square bivariate system} {{-0.3cm}}

{Input:} Two bivariate polynomials ![$p (x, y), q (x, y) \in \mathbbm{R} [x, y] .$](form_356.png)

- {{Compute the Bezout matrix

of

of  and

and  , and compute the matrices

, and compute the matrices  and

and  ;}}

;}}

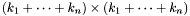

- {{Compute the generalized eigenvalues and eigenvectors of

to get the

to get the  coordinates of the roots;}}

coordinates of the roots;}}

- {{Eliminate the imaginary eigenvalues and the values at infinity, and gather the close points (with the input

);}}

);}}

- For each of {{all the close points represented by

, take the matrix

, take the matrix  of the associated eigenvectors. If their number

of the associated eigenvectors. If their number  then

then  gives a basis of

gives a basis of  ;}}

;}}

- Compute a singular value decomposition of

;

;

- {{Compute the rank of

by testing the

by testing the  until

until  is found (the rank is thus determined to be

is found (the rank is thus determined to be  );}}

);}}

- {{Let

be the

be the  first columns of

first columns of  . Define

. Define  as the first

as the first  block in

block in  , and

, and  as the second

as the second  block in

block in  ;}}

;}}

- {{Compute the generalized eigenvalues of

to get the

to get the  coordinates;}}

coordinates;}}

{Output:} an approximation of the real roots of  ,

,  . }}{}

The function which implement this algorithm is

. }}{}

The function which implement this algorithm is

- See also:

synaps/resultant/bivariate_res.h.

#include <synaps/msolve/projection/EigenRes.h>

#ifdef SYNAPS_WITH_LAPACK

using std::cout;

using std::cin;

using std::endl;

typedef MPol<double> mpol_t;

int main(int argc, char **argv)

{

mpol_t p1("16*x0^4-160*x0^2*x1^2+400*x1^4-32*x0^3+160*x0*x1^2+6*x0^2-50*x1^2+10*x0+1.5625"),

p2("x0^2-x0*x1+x1^2-1.2*x0-0.0625");

cout<<"p1="<<p1<<endl;

cout<<"p2="<<p2<<endl;

Seq<VectDse<double> > res;

Seq<int> mux,muy;

res= solve(p1,p2, EigenRes<double>(1e-3));

res= solve(p1,p2,mux, EigenRes<double>(1e-6));

res= solve(p1,p2,mux,muy, EigenRes<double>(1e-7));

cout<<"Intersection points:"<<endl;

for(unsigned i=0;i<res.size();++i)

std::cout<<"("<<res[i][0]<<","<<res[i][1]<<") of multiplicity "<<mux[i]<<" "<<muy[i]<<std::endl;

}

#else

#include <iostream>

int main()

{

std::cout <<" LAPACK is not connected"<<std::endl;

return(77);

}

#endif //SYNAPS_WITH_LAPACK

, with

, with ![$p, q \in \mathbb{R} [x, y]$](form_229.png) . It treats multiple roots, which are usually considered as obstacles for numerical linear algebra techniques. The numerical difficulties are handled with the help of singular value decomposition (SVD) of the matrix of eigenvectors associated to each eigenvalue. The extension to

. It treats multiple roots, which are usually considered as obstacles for numerical linear algebra techniques. The numerical difficulties are handled with the help of singular value decomposition (SVD) of the matrix of eigenvectors associated to each eigenvalue. The extension to  equations could be treated similarly.

equations could be treated similarly. be two square matrices of size

be two square matrices of size  . A {generalized eigenvalue} of

. A {generalized eigenvalue} of  and

and  is a value in the set

is a value in the set ![\[ \lambda (A, B) : =\{\lambda \in \mathbb{C} ; \det (A - \lambda B) = 0\}. \]](form_231.png)

is called a {generalized eigenvector} associated to the eigenvalue

is called a {generalized eigenvector} associated to the eigenvalue  if

if  . The matrices

. The matrices  . If

. If  , then

, then  can be finite, empty, or infinite. Note that if

can be finite, empty, or infinite. Note that if  then

then  . Moreover, if

. Moreover, if  , which is the ordinary spectrum of

, which is the ordinary spectrum of  .\

.\ with polynomial coefficients can be equivalently written as a polynomial with

with polynomial coefficients can be equivalently written as a polynomial with  , we obtain

, we obtain  , where

, where  are

are ![\[ \begin{array}{c} A = \left( \begin{array}{cccc} 0 & I & \cdots & 0\\ \vdots & \ddots & \ddots & \vdots\\ 0 & \cdots & 0 & I\\ T_0^t & T_1^t & \cdots & T_{d - 1}^t \end{array} \right), \hspace{0.25em} B = \left( \begin{array}{cccc} I & 0 & \cdots & 0\\ 0 & \ddots & & \vdots\\ \vdots & & I & 0\\ 0 & \cdots & 0 & - T_d^t \end{array} \right) \end{array} . \]](form_246.png)

![\[ \hspace{1em} T^t (x) v = 0 \Leftrightarrow (A - xB) \left( \begin{array}{c} v\\ xv\\ \vdots\\ x^{d - 1} v \end{array} \right) = 0. \]](form_247.png)

is an algebraically closed field and suppose given two bivariate polynomials

is an algebraically closed field and suppose given two bivariate polynomials  and

and  in

in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, y]$](form_250.png) . Our aim will be to study and compute their common roots. This problem can be interpreted more geometrically. Polynomials

. Our aim will be to study and compute their common roots. This problem can be interpreted more geometrically. Polynomials  and

and  actually define two algebraic curves in the affine plane

actually define two algebraic curves in the affine plane  (having coordinates

(having coordinates  ) and we would like to know their intersection points.

) and we would like to know their intersection points. ).

). and thus we are looking for the roots of

and thus we are looking for the roots of  . Let us denote them by

. Let us denote them by  . Then we know that

. Then we know that ![\[ p (x, 0) = c (x - z_1)^{\mu_1} (x - z_2)^{\mu_2} \cdots (x - z_s)^{\mu_s}, \]](form_257.png)

's are assumed to be distinct and

's are assumed to be distinct and  is a non-zero constant in

is a non-zero constant in  , for all

, for all  , is called the {multiplicity} of the root

, is called the {multiplicity} of the root  if

if  -axis (in other words, if the homogeneous part of

-axis (in other words, if the homogeneous part of  ). This later condition can be avoid in the projective setting: let

). This later condition can be avoid in the projective setting: let  be the homogeneous polynomial obtained by homogenizing

be the homogeneous polynomial obtained by homogenizing  , then we have

, then we have ![\[ p (x, 0, t) = c (x - z_1 t)^{\mu_1} (x - z_2 t)^{\mu_2} \cdots (x - z_s t)^{\mu_s} t^{\mu_{\infty}}, \]](form_267.png)

is an integer corresponding to the multiplicity of the root at infinity, and

is an integer corresponding to the multiplicity of the root at infinity, and  . Moreover, it turns out that the roots

. Moreover, it turns out that the roots  be two coprime polynomials in

be two coprime polynomials in  and

and  the corresponding algebraic plane curves,

the corresponding algebraic plane curves,  the ideal they generate in

the ideal they generate in ![$\mathcal{A} : = \mathbbm{K} [x, y] / I$](form_274.png) the associated quotient ring. We denote by

the associated quotient ring. We denote by  the distinct intersection points in

the distinct intersection points in  (i.e. the distinct roots of the system

(i.e. the distinct roots of the system ![\[ i (z_i, \mathcal{C}_p \cap \mathcal{C}_q) : = \dim_{\mathbbm{K}} \mathcal{A}_{z_i} < \infty, \]](form_277.png)

is here abusively (but usually) identified with its corresponding prime ideal in

is here abusively (but usually) identified with its corresponding prime ideal in  denoting the ordinary localization of the ring

denoting the ordinary localization of the ring  by this prime ideal. As a result, the finite

by this prime ideal. As a result, the finite ![\[ \mathcal{A} = \mathcal{A}_{z_1} \oplus \mathcal{A}_{z_2} \oplus \cdots \oplus \mathcal{A}_{z_s} \]](form_281.png)

-axis. To do this let us see both polynomials

-axis. To do this let us see both polynomials ![$A [y]$](form_283.png) where

where ![$A : = \mathbbm{K} [x]$](form_284.png) , that is to say as univariate polynomials in

, that is to say as univariate polynomials in ![\begin{equation} \label{A[x]} p (x, y) = \sum_{i = 0}^{d_1} a_i (x) y^i, \hspace{.2cm} q (x, y) = \sum_{i = 0}^{d_2} b_i (x) y^i . \end{equation}](form_285.png)

and

and  do not vanish simultaneously, as

do not vanish simultaneously, as

's are distinct elements in

's are distinct elements in  (as sets). For instance, if all the

(as sets). For instance, if all the  are distinct then we have

are distinct then we have  and

and  for all

for all  , the integer

, the integer  equals the sum of all the intersection multiplicity of

equals the sum of all the intersection multiplicity of  such that

such that  .

.  's are distinct (this can be easily obtained by a linear change of coordinates

's are distinct (this can be easily obtained by a linear change of coordinates  is nothing but the valuation of

is nothing but the valuation of  at

at  . Another corollary of this result is the well-know Bezout theorem for algebraic plane curves, which is better stated in the projective context. Let us denote by

. Another corollary of this result is the well-know Bezout theorem for algebraic plane curves, which is better stated in the projective context. Let us denote by  the homogeneous polynomials in

the homogeneous polynomials in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, y, t]$](form_302.png) obtained from

obtained from  points in

points in  , counted with multiplicities.

, counted with multiplicities.  is a homogeneous polynomial in

is a homogeneous polynomial in ![$\mathbbm{K} [x, t]$](form_306.png) of degree

of degree  the Sylvester matrix of

the Sylvester matrix of  . From [*] , we deduce immediately that

. From [*] , we deduce immediately that  vanishes at a point

vanishes at a point  if and only if either there exists

if and only if either there exists  such that

such that  , or either

, or either  (in which case the intersection point is at infinity). Therefore one may ask the following question : being given a point

(in which case the intersection point is at infinity). Therefore one may ask the following question : being given a point  such that

such that  , how to recover all the possible point

, how to recover all the possible point  and

and  are not both zero. If

are not both zero. If  is of dimension one, then it is easy to check that there is only one point

is of dimension one, then it is easy to check that there is only one point  is a multiple of the vector

is a multiple of the vector ![$[1, y_0, \cdots, y_0^{d_1 + d_2 - 1}]$](form_319.png) . Therefore to compute

. Therefore to compute  be any basis of the kernel

be any basis of the kernel  ,

,  be the matrix whose

be the matrix whose  row is the vector

row is the vector  ,

,  be the

be the  -submatrix of

-submatrix of  corresponding to the first

corresponding to the first  columns and

columns and  be the

be the  . Then

. Then  is the set of roots of the equations

is the set of roots of the equations  (i.e. the set of

(i.e. the set of  .

.  is always strictly greater than the

is always strictly greater than the  .

. from the Sylvester matrix. However, instead of the Sylvester matrix we can use the Bezout matrix to compute

from the Sylvester matrix. However, instead of the Sylvester matrix we can use the Bezout matrix to compute ![$\tmop{Res} (p, q) \in A [x]$](form_336.png) (see section [*] ). This matrix have all the required properties to replace the Sylvester matrix in all the previous results, except in proposition

(see section [*] ). This matrix have all the required properties to replace the Sylvester matrix in all the previous results, except in proposition ![\[ \max (\deg (p (x_0, y), \deg (q (x_0, y)) > \deg (\gcd (p (x_0, y), q (x_0, y)) . \]](form_337.png)

in the system

in the system ![\[ \left\{ \begin{array}{l} p (x, y) = x^2 y^2 - 2 y^2 + xy - y + x + 1\\ q (x, y) = y + xy \end{array} \right. \]](form_339.png)

(or the Bezout matrix) for each root

(or the Bezout matrix) for each root  . Numerically, some of these values can contain a nonzero imaginary part. Generally such a problem is encountered for multiple eigenvalues.

. Numerically, some of these values can contain a nonzero imaginary part. Generally such a problem is encountered for multiple eigenvalues. , and any eigenvalue whose imaginary part is of absolute value less than

, and any eigenvalue whose imaginary part is of absolute value less than  with corresponding generalized eigenvectors

with corresponding generalized eigenvectors

with

with  . We define

. We define  Then, if

Then, if  block of

block of  ; i.e. this algorithm can be used to gather clusters of

; i.e. this algorithm can be used to gather clusters of  the matrix of the associated eigenvectors, then the singular value decomposition of

the matrix of the associated eigenvectors, then the singular value decomposition of ![\[ E = U \Sigma V^t, \tmop{with} \Sigma = \left( \begin{array}{cccccc} \sigma_1 & & & & & \\ & \ddots & & & & \\ & & \sigma_r & & & \\ & & & 0 & & \\ & & & & \ddots & \\ & & & & & 0 \end{array} \right) \hspace{1em} \]](form_351.png)

is the rank of

is the rank of ![\[ E' = E \cdot V = U \cdot \Sigma = [\sigma_1 u_1 \cdots \sigma_r u_r \hspace{0.25em} 0 \cdots 0] = [e'_1 \cdots e'_r \hspace{0.25em} 0 \cdots 0] . \]](form_352.png)

is also a matrix of eigenvectors, because the changes are done on the columns, and V is invertible. Hence

is also a matrix of eigenvectors, because the changes are done on the columns, and V is invertible. Hence ![$E'' = [e'_1 \cdots e'_r]$](form_354.png) is a matrix of linearly independent eigenvectors. Consequently

is a matrix of linearly independent eigenvectors. Consequently  can be used to build

can be used to build ![$p (x, y), q (x, y) \in \mathbbm{R} [x, y] .$](form_356.png)

of

of  , take the matrix

, take the matrix  then

then  ;}}

;}} until

until  is found (the rank is thus determined to be

is found (the rank is thus determined to be  . Define

. Define  block in

block in  to get the

to get the  ,

,  . }}{}

. }}{}