by Nataliia Bielova, 17 May 2019

Disclamer: I am a computer science researcher at the Inria Sophia Antipolis research institute and my goal is to increase awareness of people about privacy and the impact of technology on their lives. I've not been working with journalists yet and this post may not present their point of view.

In the past decades we've seen how companies increasingly collect and use our data on a large scale without our knowledge. Such practices, or "the business model of the Web", became "the norm" and we started thinking there is no way to know what is going on and no way to regain our privacy. Companies have also been using machine learning algorithms to extract and infer new information from the collected data and using this to make automatic decisions about people's lives, often introducing discrimination and bias.

Luckily, we have seen that tech journalists and scientists have started investigating how much data is actually collected by companies, how we are tracked online, and what advertising agencies got to know about us. We've seen some investigations on how the collected data is used against us. Prominent examples of such revelations were done by tech journalists who impressed the public with their revealing articles on the impact of technology on society. Julia Angwin and Kashmir Hill1 are the most known and highly respected tech reporters of today. Here are some examples of their work:

Did you notice a pattern in this list? The best tech journalists have not done these studies alone, they were collaborating with computer science engineers! Surya Mattu, Ashkan Soltani, Dhruv Mehrotra, and many others were hired by journalists to investigate how technologies work and how data is collected, and indeed co-authored all these great articles. This shows that data-investigators really need to have engineers with a computer science background at their side to help them realize their investigations. Now, imagine yourself a tech journalist: you just came up with an original idea, but now you need an engineer (whom you should also pay) to get the technical job done.

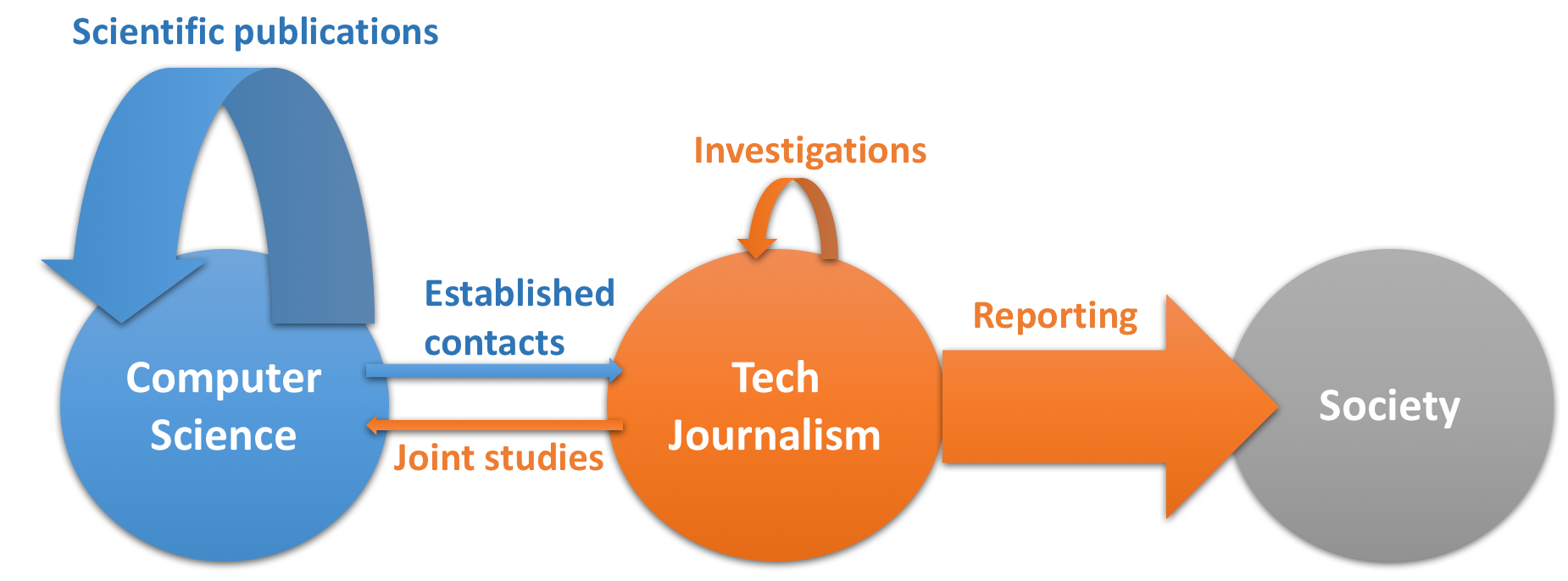

However, having engineers present in a newsroom is not enough. In her recent presentation at IJF'19, Julia Angwin explained that in many newsrooms journalists don't work side-by-side with engineers. Instead, journalists ask the so-called ``data team as a service desk'' to provide evidence for the hypothesis they want to investigate. Julia Angwin argues that instead of such service desks, tech journalists should use scientific methods in order to validate their hypotheses. In order to make a sound study, journalists should do hypothesis testing, large-scale or crowd-sourced data collection, and deep data analysis.

from Julia Angwin's talk at IJF'19

from Julia Angwin's talk at IJF'19

But wait! Computer scientists are already using scientific methods to test hypotheses about massive data collection, political ads on Facebook, detecting discrimination and many other aspects of technologies that have a strong impact on society. Moreover, scientists are already paid by their corresponding institutions, so why aren't the collaborations between journalists and scientists happening?

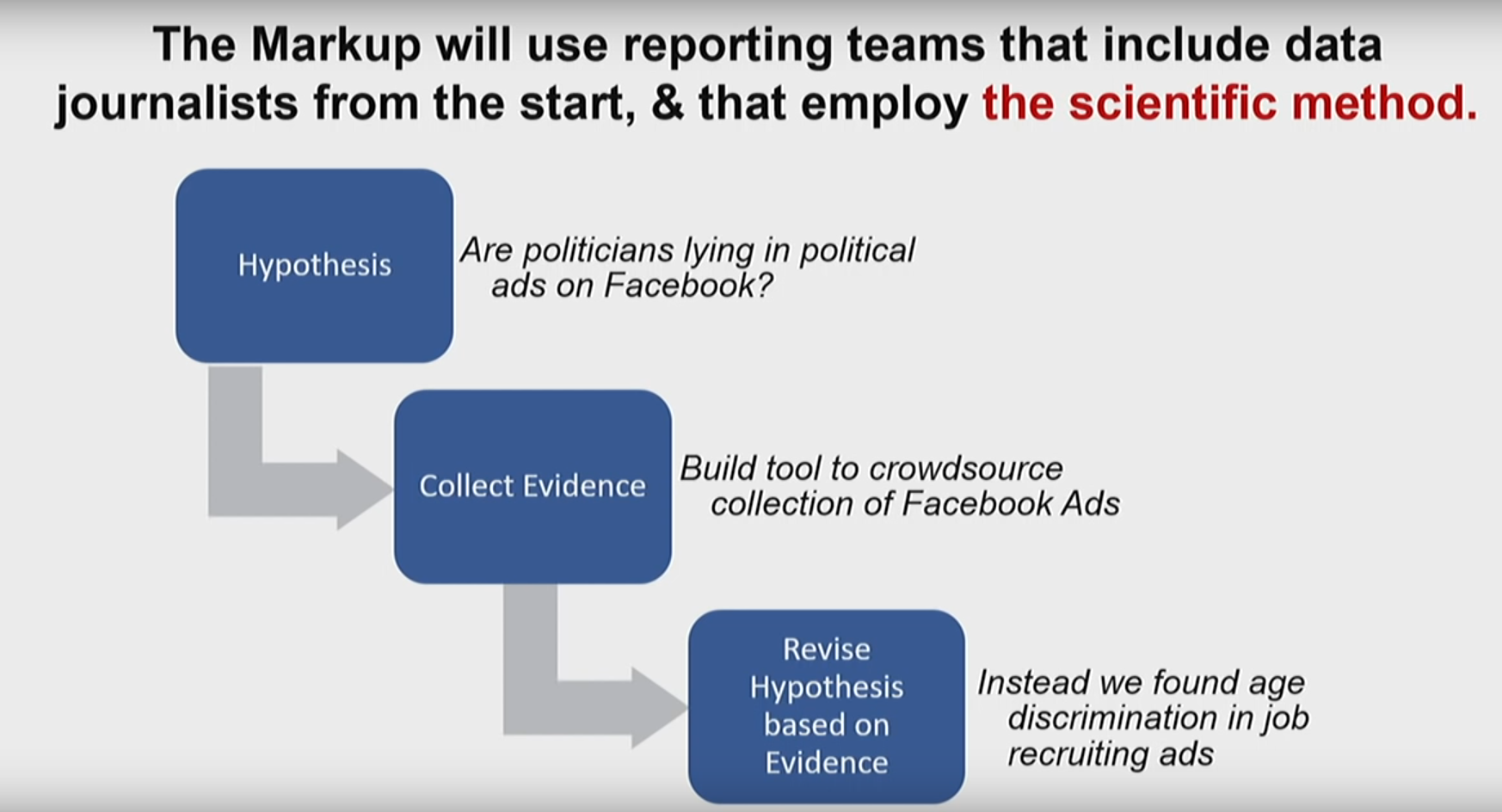

Scientists today are doing excellent studies on technologies' impact on society. They have been looking into the various technologies companies use to track users when they browse the Web or to extract personal data from their smartphones; they've been deeply analyzing Facebook advertising ecosystem and publishing their results in top-level international scientific conferences and journals.

But how many of these studies have the general public heard of?

Only a few computer scientists have managed to establish strong relationships with tech journalists, and hence the public. They have made building such relationships a priority in their busy schedules and some of them succeeded. But such cases are rare and the successful scientists are often senior researchers or tenured professors, who can afford the time and effort. Sometimes, their institutions help them in reaching out to journalists, but this is not a general rule in many institutions.

| Problem 1: Most of the scientists, and especially junior faculty members, do not even know whom to contact to reach the popular press even though their research results has a direct and high impact on society. |

|---|

In my experience, when young scientists manage to reach the general public, it often happens accidentally. Imagine a high-impact paper appears in a top-level academic venue and the scientist has also published a blog post with a summary of the major results3. The journalists would find the academic paper, check the blog post, and write their media press article about the research outcome, often without even contacting the paper's author, or perhaps even forgetting to cite the author or their institution. This has recently happened to my PhD student, Dolière Francis Somé, whose work has been covered in more than 80 media posts, but none of the journalists have contacted him directly. It also happens that journalists misinterpret some details of the results, ending up publishing stories that have errors.

Nevertheless, scientists are generally happy when the popular press notices their work and publish about them (despite the bitter taste left in their mouths from seeing errors and misinterpretations). It became a trend for scientists to add media coverage under the publications on their homepages to show how their results impact the real world. Here is one example from Oana Goga, a computer science researcher at CNRS:

Some scientists take a different path. They succeed in making their results public even before their academic publication and manage to get the press coverage before the paper is accepted, probably by collaborating with their established connections with journalists. For example, Arvind Narayanan and Steven Englehardt got media coverage for their study on online tracking on 1 million websites while the paper was under submission. It was then accepted at the top security conference, ACM CCS 2016.

But why would scientists not try to publicize their results in popular media before publishing in an academic conference?

The main criteria to evaluate a scientist's advancement during their career is their academic publications record.

When a scientist submits a paper for publication at a conference, the paper is reviewed by renown researchers in the field. One of the main criteria for evaluation is the work's "originality" - ideally, the paper should be the first to shed light on a new problem. The top security and privacy conferences these days are following the "anonymous submission" (also called "double-blind review") process4. Following this process, reviewers do not get to know the authors' names when they evaluate the paper.

Imagine you've done an excellent study, for example revealing the new practices of online trackers. You submit it to the top-level conference and at the same time contact the media to write about your results. The media can act and publish quickly, but the academic review process takes at least 3 months. Now reviewers read the media and at the same time read your paper (without knowing it's you who wrote it, due to "anonymous submission"). The reviewers are no longer convinced of "originality" of your research because someone else (you!) have already published these results on the media!

Nick Nikiforakis, a computer science professor at Stony Brook University, wrote about this issue in his blog series on "Poor reasons to reject a computer security paper" back in 2016:

“A blog post has shown this”

TLDR: Don’t reject scientific papers on the basis of three-paragraph blog posts.

This is, hands down, one of the most common comments I have seen in reviews. What it typically amounts to is that there exist some 3-paragraph blog post which indeed has been on the same topic and even matches one or more of the statistics or lessons learned by the currently reviewed paper. Naturally, a 12-page paper, will have tens of experiments that systematically assess the problem, measure it across novel dimensions, compare it with related work, offer countermeasures and, in general, present a much more complete treatment and analysis of a problem and its solutions.

Many security reviewers, however, in their endless pursuit of novelty and vulnerabilities, now treat this topic as tainted. The blog post that was written prior to the submission of this paper somehow subtracts from the value of the paper. The topic discussed in the paper suddenly becomes “well known” and all the extra work is now mere “details.”

So scientists face the fear of being rejected just because they have revealed their findings "too early".

| Problem 2: Scientists delay publication in the media because they fear their academic paper will be rejected. |

|---|

The computer science research community in the field of security and privacy needs to address this problem. When a high-impact scientific study has already gone to the popular press, it should not impede a scientific publication at top-level academic venues. And moreover, the "anonymous submission" process should not be applied to researchers whose names and results have already appeared in the popular press.

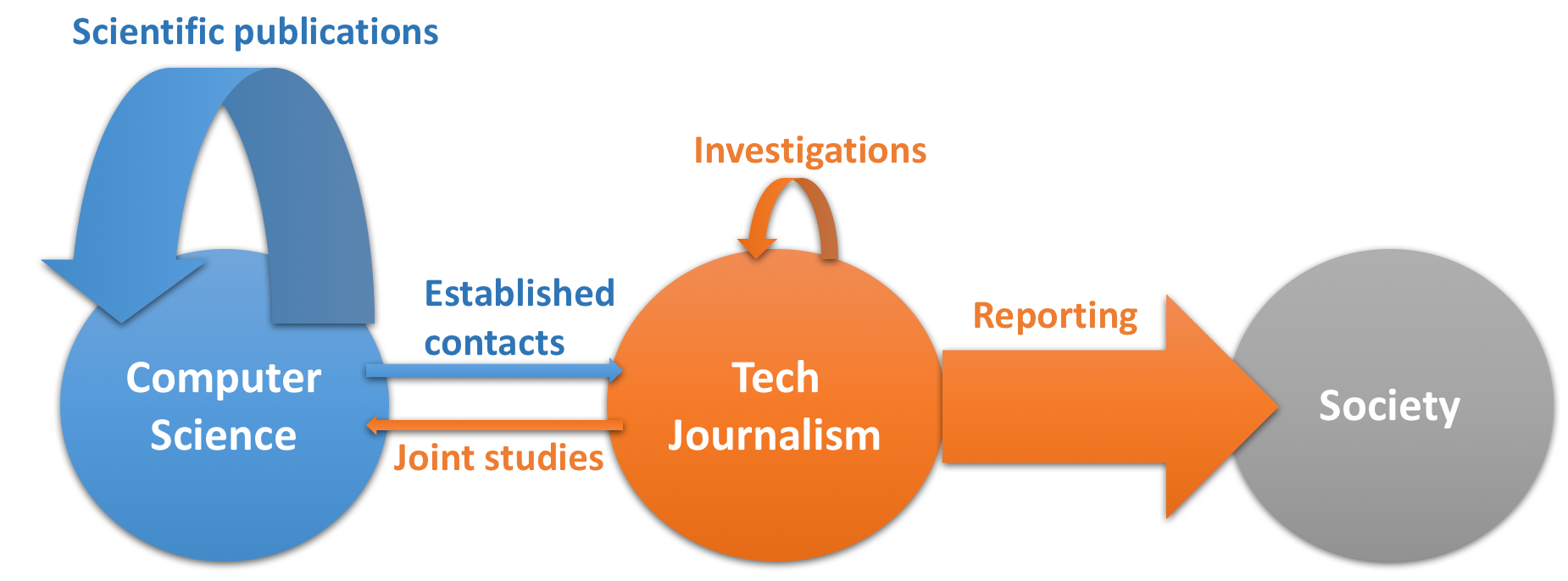

Currently, scientists make numerous studies, advance the scientific methods, and publish their results in top-level conferences. Tech journalists make smaller scale investigations and report to general public on a large scale. Unfortunately, only few scientists have established contacts with journalists, and only few journalists have reached out to scientists to make joint studies.

So what should journalists and scientists do? They need to find new ways to collaborate. Tech journalists would like to test new hypothesis but need advanced scientific methods that scientists know and use on a daily basis. Scientists deeply analyse how new technologies work but often do not know what study would have the biggest impact on society and how to communicate their results to the general public.

| Proposal: let's set up a collaboration between tech journalists and scientists and start doing science-driven journalism! |

|---|

This will not solve the problem of the scientific reviews and the scientist's fear of publication rejection. However, if we show that such collaborations bring strong results and have a real impact on society, then there is a hope that the academic community will follow our lead, changing the way they go about the evaluation of scientific papers with strong impact on society.

Acknowledgements: Big thanks goes to Dave Choffnes, Paul-Olivier Dehaye, Janet Bertot, Oana Goga, Celestin Matte, and Mathieu Cunche for their great feedback and suggestions for this post.

PS: If you like this article, please share it on your social media! If you use Twitter, please use the tag #sciencedrivenjournalism so that we can follow the discussions about this online!

Both Julia Angwin and Kashmir Hill were mysteriously fired at the end of April 2019. It's really devastating to see this happening, and privacy community is actively expressing their disappointment on social media:

Ok so... @JuliaAngwin and @kashhill out of their reporting job in like a week... this is a huge loss for tech journalism and privacy advocacy. What the hell are the people responsible for this thinking? Both wrote some of the best articles I’ve ever read around those issues! ↩

— Geoffrey Delcroix (@geoffdelc) May 1, 2019

Since their publicaiton, The Wall Street Journal has put a paywall to the original articles, so I put a link to Ashkan Soltani's blog post instead that listed some examples from the "What They Know" series. ↩

If the scientist doesn't publish an extraction of his or her results on a website, or in a video post, journalists are not likely to write about the work, because reading a 12-page 2-column scientific paper in 10-point font takes too much time. ↩

The top-level security and privacy conferences I mentioned are the reknown top-4 international security conferences, NDSS Symposium, Usenix Security, IEEE Security and Privacy and ACM CCS, together with top privacy symposium PETs and TheWeb conference. ↩