This page contains the description of the following commands

\i \I,

\@ident,

\idotsint,

\ieme,

\iemes,

\ier,

\iere,

\ieres,

\iers,

\if,

\@ifbempty,

\ifcase,

\ifcat,

\@ifclasslater,

\@ifclassloaded,

\@ifclasswith,

\ifcsname,

\ifdefined,

\ifdim,

\ifeof,

\iff,

\iffalse,

\IfFileExists,

\iffontchar,

\ifhbox,

\ifhmode,

\ifinner,

\ifmmode,

\@ifnextchar,

\@ifnextcharacter,

\ifnum,

\ifodd,

\@ifpackagelater,

\@ifpackageloaded,

\@ifpackagewith,

\@ifstar,

\if@tempswa,

\@iftempty,

\ifthenelse,

\iftrue,

\@ifundefined,

\ifvbox,

\ifvmode,

\ifvoid,

\ifx,

\ignorespaces,

\iint, \iiint, \iiiint,

\ij,

\IJ,

\Im,

\ImaginaryI,

\imath,

\immediate,

\implies,

\in,

\in@,

\include,

\includeonly,

\includegraphics,

\indent,

\index,

\internal,

\interfootnotelinepenalty,

\interdisplaylinepenalty,

\inf,

\infty,

\injlim,

\inplus,

\input,

\input@encoding,

\input@encoding@default,

\input@encoding@val,

\Input,

\InputClass,

\InputIfFileExists,

\inputlineno,

\insert,

\insertbibliohere,

\insertpenalties,

\int,

\interactionmode,

\intercal,

\interleave,

\interlinepenalties,

\interlinepenalty,

\intertext,

\intextsep,

\InvisibleComma,

\InvisibleTimes,

\iota,

\isodd,

\isundefined,

\it,

\item,

\@item,

\@@item,

\@itemlabel,

\itemindent,

\itemsep,

\itshape,

\@iwhiledim,

\@iwhilenum,

\@iwhilesw,

\@ixpt,

and environments

imagesonly,

itemize,

and the ifthen package.

The \i command is valid in math mode and text mode. It generates an i without dot (Unicode U+131, ı). The \I command expands to I, but is converted to \i by \MakeLowercase.

See description of the \qquad command and \AA command.

The \@ident command is another name for \@firstofone, it takes an argument and returns it.

The command \idotsint behaves \int...\int, except that it is declared as single operators with limits (an index will be under the whole expression).

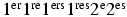

The \ier command translates to &ier;, an entity defined by the raweb. Behavior changed in version 2.8.2, see example below and here.

The \iere command translates to &iere;, an entity defined by the raweb. Behavior changed in version 2.8.2, see example below and here.

The \iers command translates to &iers;, an entity defined by the raweb. Behavior changed in version 2.8.2, see example below and here.

The \ieres command translates to &ieres;, an entity defined by the raweb. Behavior changed in version 2.8.2, see example below and here.

The \ieme command translates to &ieme;, an entity defined by the raweb. Behavior changed in version 2.8.2, see example below and here.

The \iemes command translates to

&iemes;, an entity defined by the raweb.

Behavior changed in version 2.8.2, see here.

Example

1\ier 1\iere 1\iers 1\ieres 2\ieme 2\iemes

Translation:

1&ier;1&iere;1&iers;1&ieres;2&ieme;2&iemes;

Part of the raweb dtd that defines the entities:

<!ENTITY ier "<hi rend='sup'>er</hi>"> <!ENTITY iers "<hi rend='sup'>ers</hi>"> <!ENTITY iere "<hi rend='sup'>re</hi>"> <!ENTITY ieres "<hi rend='sup'>res</hi>"> <!ENTITY ieme "<hi rend='sup'>e</hi>"> <!ENTITY iemes "<hi rend='sup'>es</hi>">

Preview:

If a standalone XML document is required, it is not possible to insert entities like those defined above; the first idea was then to insert the replacement text, so that the translation of \ieme would be <hi rend='sup'>e</hi>. However, it is better to translate this the same way as \textsuperscript{e} (see \rm for how to change the translation of font commands). Since version 2.8.2, this is the translation of \ier and friends, as well as \numero and friends. Moreover, the \xspace is inserted, so that a space after the command remains in most cases. Note that frenchb defines these as \def\ier{\up{\lowercase{er}}\xspace} and \DeclareRobustCommand*{\no}{n\up{\lowercase{o}}\kern+.2em} . Translation:

1<hi rend='sup'>er</hi> 1<hi rend='sup'>re</hi> 1<hi rend='sup'>ers</hi> 1<hi rend='sup'>res</hi> 2<hi rend='sup'>e</hi> 2<hi rend='sup'>es</hi> n<hi rend='sup'>o</hi> N<hi rend='sup'>o</hi>

The \if command is used to compare two tokens. For instance \if AB evaluates to false, \if AA evaluates to true. See below for what happens after the test is found true or false. The token after \if is expanded, until an non-expandable token is found. This is done twice, and these two tokens are compared. (if \else or \fi is seen when scanning, then \relax is inserted, see last two examples). If you say \def\foo{}\def\bar{OOK!}, then \if\foo\bar will be true, because O is compared to O (and two characters are left to be read-again). Two characters compare equal if the have the same internal code (regardless of their \catcodes). Two commands compare equal, and a command is never a character.

{%The command \BUG is not evaluated in this example

\if00 \else \BUG\fi

\if01 \BUG\fi

\if\par\relax \else \BUG\fi

\if0\par \BUG\fi

\count0=1000

\if\romannumeral\count0m \else \BUG\fi %Two M, different catcode

\if\romannumeral\count0n \BUG\fi

\if\number\count0 \BUG\fi%this compares 1 with 0

\count0=1100

\if\number\count0 \else \BUG\fi

\catcode `[=13 \catcode`]=13 \def[{*}

\if\noexpand[\noexpand] \BUG \fi %this compares [ and ]

\if[* \else \BUG \fi

\if\noexpand[* \BUG\fi

\def\foo{01}\def\xfoo{00}

\if\xfoo \else\BUG\fi

\if\foo\par \BUG\fi

\if\noexpand\foo\par \else\BUG\fi

\if\par\noexpand\foo \else\BUG\fi

\if0\noexpand\foo \BUG\fi

\if0\noexpand\foo \BUG\fi

\if\par\else \BUG\fi

\if\else \BUG\fi

}

There are several conditionals, that share the same structure. A construction like\if AB X\else Y\fi evaluates to Y, because comparing A and B gives false, so that everything up to the \else token is discarded. On the other hand, \if AA X\else Y\fi evaluates to X (there is a space before the X). In this case everything between \else and \fi is discarded. In some cases (in a \edef or after \expandafter) it is important to specify the exact meaning of ``evaluation''. In fact, all conditional tokens (\if, \else, \fi, etc.) can be expanded.

The first operation involved in an \if-like command is to determine the truth value (in the case of \if ABCD the tokens A and B are read, compared, found unequal; the test is false, characters CD are not yet read; in the case of \unless\if ABCD, comparison yields false and the test is true). If the test is true, this is remembered (a special token is pushed on the conditional stack), expansion is finished. If the test is false, tokens are read, up to \else or \fi. If \fi is seen, expansion of the conditional is terminated. Otherwise, expansion is also terminated, but the fact that the condition is not yet finished is remembered (a token is pushed on the conditional stack).

The case of \ifcase\foo c0\or c1\or c2 \or c3 \else c4\fi is special. Here the quantity \foo should evaluate to an integer. The expansion is c0 if the integer is 0, c1 if the integer is one, c2 if the integer is 2, c3 if the integer is 3, and c4 otherwise. If the integer is 0, expansion is complete, and an if-case conditional is pushed on the stack. Otherwise, all tokens up to \or, \else or \fi are discarded. If \fi is seen, the situation is the same as in the case \iffalse without \else part. If \else is seen, the situation is the same as in the case \iffalse with an \else part. Otherwise, this scanning is repeated N times (when N is the value of \foo). Expansion is then terminated (an if-case conditional is pushed on the stack). (in the example above, if the integer is 2, everything is read, but c2 \or c3 \else c4\fi).

When a command like \fi, \else, \or is seen, different things can happen. If the conditional stack is empty, it is an error. An \or token is valid only if the stack contains a if-case conditional; all tokens up to the next \fi are discarded. An \else token is valid everywhere (but not after \else); all tokens up to the next \fi are discarded In each case, the conditional is terminated, and the stack is popped. The \loop command uses \expandafter\iterate\fi. The idea is to pop the conditional stack before calling \iterate, this avoids overflowing the stack.

In the discussion above, it is the value of the token that imports, not its name. After \let\Else\else, you can use \Else instead of \else. After \def\myelse{\else}, you can say \if AA\X\myelse Y\fi: the \myelse command is expanded after \X is evaluated (let's assume that evaluating \X does not read the token that follows, start another conditional, etc). In the case \if AB \X\myelse Y\fi the test is false, and \X is not evaluated, \myelse neither. Thus \myelse is not recognized as an \else.

In a case like \if... \ifhph...\fi ... \else ... \fi you can say \def\yes{\if00} and \let\ifhph\yes. If the test is true, then \ifhph is expanded and considered as a conditional, otherwise it is not; as a consequence, the first \fi terminates the inner or the outer \if and the second \fi is sometimes spurious. The \iftrue command has the same meaning as \yes, but it is always recognized as a conditional.

You can say things like \count0=2\ifnum\count0=\count13\fi4. The important point is that the scanint routine calls expand in order to get the next digit, hence interprets conditionals. You would expect 24 to be put in \count0. After \tracingall the following code

\count0=7 \count1=7 \count0=2\ifnum\count0=\count1 3\fi4

produces the following lines in the transcript file.

[2956] \count0=2\ifnum\count0=\count1 3\fi4

{\count}

+scanint for \count->0

+\ifnum1238

+scanint for \count->0

+scanint for \ifnum->7

+scanint for \count->1

+scanint for \ifnum->7

+iftest1238 true

+\fi1238

+scanint for \count->234

{changing \count0=7 into \count0=234}

You can see here that each conditional has a number (used only for debugging purposes). In this example, the scanning of the number that is put in \count0 is ended by the space induced by the end of line. The \ifnum test uses the old value.

Same example, as above, without the space in \count13. We assume that \count0=7 and \count13=0 The test is false, and 24 is put in \count0.

[2961] \count0=2\ifnum\count0=\count13\fi4

{\count}

+scanint for \count->0

+\ifnum1239

+scanint for \count->0

+scanint for \ifnum->7

+\fi1239

+scanint for \count->13

+scanint for \ifnum->0

+iftest1239 false

+\fi1239

+scanint for \count->24

{changing \count0=7 into \count0=24}

If you wonder why \fi1239 appears twice, let's consider this

\count0=7 \count13=7 \count0=2\ifnum\count0=\count13\fi4

Here, the test is true. The transcript file says:

[2967] \count0=2\ifnum\count0=\count13\fi4

{\count}

+scanint for \count->0

+\ifnum1240

+scanint for \count->0

+scanint for \ifnum->7

+\fi1240

+scanint for \count->13

+scanint for \ifnum->7

+iftest1240 true

+scanint for \count->2

{changing \count0=7 into \count0=2}

{\relax}

+\fi1240

Character sequence: 4 .

What happens is the following: when \fi1239 or \fi1240 is seen, the truth value of the condition is not yet known, because the number in \count13 is not evaluated. In such a case, TeX pushes back the \fi and inserts \relax. Tralics does the same. Hence, the expression that is effectively interpreted is \count0= 2\ifnum \count0 =\count 13\relax \fi 4 (spaces added for readability). Thus, the expansion of \if...\fi is empty if the test is false, \relax otherwise. So the full expression is \count0=24 if the test is false \count0=2\relax4 otherwise.

What about {\def\relax{0}\xdef\foo{\ifnum0=0\fi}} ? This puts \relax in \foo. There is a trick: this token is not the same token as the one that follows the \def, since otherwise 0\fi would expand to 0\relax\fi then 00\fi, then 00\relax\fi without end (and without overflow).

The \ifcase command reads a number, and expands according to some clauses. See \if... for details. We give as an example of how to convert a character into a letter. Here, if the argument is not a number, an error is signaled. If the value if zero, the expansion is empty. If the number is negative or greater then 26, the expansion is \@ctrerr. There is also the macro used by the babel system for typesetting German months; no error is signaled for invalid month values.

\def\@alph#1{%

\ifcase#1\or a\or b\or c\or d\or e\or f\or g\or h\or i\or j\or

k\or l\or m\or n\or o\or p\or q\or r\or s\or t\or u\or v\or w\or x\or

y\or z\else\@ctrerr\fi}

\def\month@german{\ifcase\month\or

Januar\or Februar\or M\"arz\or April\or Mai\or Juni\or

Juli\or August\or September\or Oktober\or November\or Dezember\fi}

The \ifcat command is used to compare two tokens. For instance \ifcat a0 evaluates to false, \ifcat AB evaluates to true. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false. Tokens after \ifcat are evaluated, until unexpandable tokens remain, they are compared via catcodes (non-character tokens have \catcode16 in this test).

{%The command \BUG is not evaluated in this example

\ifcat a0 \BUG\fi

\ifcat $^ \BUG\fi %$

\ifcat 01 \else \BUG\fi

\ifcat AB \else \BUG\fi

\count0=1000

\ifcat\romannumeral\count0m \BUG\fi %First m is not letter

\count0=1100

\ifcat\romannumeral\count0m \else \BUG\fi %Compares m and c

\ifcat\number\count0 3\else \BUG\fi

\ifcat\par\relax \else \BUG\fi

\ifcat0\par \BUG\fi

\catcode `[=13 \catcode`]=13 \def[{*}

\ifcat\noexpand[\noexpand] \else \BUG \fi

\ifcat[* \else \BUG \fi

\ifcat\noexpand[* \BUG\fi

}

The commands \@ifclasslater or \@ifpackagelater take four arguments, P, D, A and B; they evaluate the token list A in case the class or package P is loaded with a date more recent than D, the token list B otherwise.

The commands \@ifclassloaded and \@ifpackageloaded take three arguments, P, A and B; they evaluate the token list A in case the class or package P is loaded, the token list B otherwise.

The commands \@ifclasswith or \@ifpackagewith take four arguments, P, L, A and B; they evaluate the token list A in case the class or package P is loaded with options L, the token list B otherwise. The order of elements in L is irrelevant, the test is true if the package has been loaded with additional options.

The command \ifcsname is a conditional, defined by ε-TeX. It reads and expands all tokens as \csname, until finding \endcsname. The condition is true if the token exists and is defined. If the token does not exists, it will not be created. In LaTeX, \@ifundefined call \csname, but has as side effect that the resulting token is never undefined. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false.

The command \ifdefined is a conditional, defined by ε-TeX. It reads a token and its truth value is true if this token is defined. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false.

The \ifdim command is used to compare two dimensions. For instance \ifdim 0pt<1pt evaluates to true, \ifdim 0cm=1cm \ifdim 0ex>1ex evaluates to false. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false. The dimensions are read by scandimen (scanning a dimension may involve macro-expansion, hence evaluation of conditionals). The first dimension must be followed by optional spaces and a character (of \catcode 12) chosen among <, =, >. Examples.

\ifdim 0pt<1pt \else\BUG\fi

\ifdim 0pt=1pt \BUG\fi

\ifdim 0pt>1pt \BUG\fi

\ifdim -3pt<-2pt \else \BUG\fi

\ifdim -3pt=-2pt \BUG\fi

\ifdim -3pt>-2pt \BUG\fi

\def\equalsign{=}

\ifdim 1\ifnum2<3 4\else6\fi pt\equalsign 14pt \else \BUG \fi

\ifdim 1\ifnum2>3 4\else6\fi pt\equalsign 14pt \BUG \fi

These two commands take 3 arguments, L, A, B they evaluate A if L is empty, and B otherwise. The command \@ifbempty removes blank spaces in its first argument; the command \@iftempty does nothing special, it could be defined as

\long \def \@iftempty#1{%

\ifx @#1@%

\expandafter \@firstoftwo \else

\expandafter \@secondoftwo \fi

}

The two commands \@firstoftwo and \@secondoftwo are implemented in Tralics version v2.7 (the code is trivial, see below); thanks to the \expandafter they are evaluated after the \fi, this allows arguments A and B to be commands that read some arguments. The definition that follows comes from amsart, it matches the semantics of the Tralics command \@ifbempty (which is more efficient, since it uses a C++ command for testing that the token list contains only spaces).

\let\@xp=\expandafter

\def\@firstoftwo#1#2{#1}

\def\@secondoftwo#1#2{#2}

\long\def\@ifempty#1{\@xifempty#1@@..\@nil}

\long\def\@xifempty#1#2@#3#4#5\@nil{%

\ifx#3#4\@xp\@firstoftwo\else\@xp\@secondoftwo\fi}

The behavior of this code is the following. We take the first argument, append two at-sign characters, two dots, and a special token, then read everything up to the special token. You lose if the special token appears in the argument. Otherwise, the first token is discarded, the test is: are the two tokens after the first at-sign the same. Case one, the argument is empty: we discard the first at-sign, compare the two dots, and the test is true. Case two: there is no at-sign in the first argument, the test compares the at-sign and the dot, the test is false. Case three: there is an at-sign in the argument, and the result may be unexpected. Notice that category codes have to match; the at-sign in \@xifempty has category letter (otherwise the command name is illegal), so the macro has the correct behavior if it contains normal (non-letter) at-sign characters.

Note that when the outer macro calls the inner one, a pair of braces can be removed, so that, if the argument is { }, only the space is transmitted, and then ignored when the inner macro looks for the first argument (since this is an undelimited argument).

You can say \ifeof N ... \else ...\fi. Here N must be a valid input channel number (between 0 and 15, see scanint for details). The test is true, unless channel N is opened and not yet closed. See \openin for an example. See \if... for what happens in case the test is true.

The \iff command (if and only if) is an other name for \Longleftrightarrow. The translation is <mo>⟺</mo> (Unicode U+21D4, ⇔). See also description of the \smallint command.

The command \iffalse is a conditional whose truth value is always false. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false. See the TeXbook chapter 20 for usefulness of such a command.

If you say \IfFileExists{name}{true-code}{false-code}, then Tralics converts name into a character string, and tries to open a file of this name. In the case of success, true-code is executed, otherwise false-code is executed. The command can be followed by an optional plus sign. If this case Tralics checks for the name in the current directory only. Otherwise, the file is searched in the input path; moreover, if the name is not terminated by `.tex', then the extension is added and the file is searched again.

In the example that follows, no error message should be printed

\IfFileExists{nohope}{\errmessage{bad1}}{}

\IfFileExists{\jobname}{}{\errmessage{bad2}}

The command \iffontchar is a conditional; it reads a font identifier, and a character position, and evaluates to true in the case where this character is defined in the font. For instance \iffontchar\font`a 1\else 2\fi evaluates to 1, unless the current font does not contain the letter a (this is not a very useful font). Since Tralics does not read font metric files, nothing special happens, we pretend that the character exists, unless the font is the null font. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false.

The command \ifhbox is a conditional; it reads a box number N, the test is true if the box contains a hbox. In Tralics, N should be a number between 0 and 1023. The test is always false (because box registers contain XML elements, that are neither hbox nor vbox). See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false.

This tests if the current mode is horizontal mode. See \ifvmode for details.

This tests if the current mode is inner (restricted) mode. See \ifvmode for details.

This tests if the current mode is math mode. See \ifvmode for details.

You can say \@ifnextchar{char}{yes-code}{no-code}. The result depends on the token that follows. If this token is the same as the first argument, then yes-code is executed, otherwise no-code is executed. The first argument should be a single token (for instance a character). Spaces are ignored. There is a variant \@ifnextcharacter where the test is true if the two tokens are character tokens with same value and possibly different category code; In LaTeX, \futurelet is used to grab the next character. Example.

\def\normal#1#2{=#1=#2=}

\def\withbrackets[#1]#2{\normal{#1}{#2}}

\def\withoutbrackets#1{\normal{}{#1}}

\def\foo{\@ifnextchar[\withbrackets\withoutbrackets}

\foo[1]{2}\foo34

This is the content of the transcript file that shows the expansion of the two occurrences of \foo.

\foo->\@ifnextchar [\withbrackets \withoutbrackets

{\@ifnextchar}

{\@ifnextchar true}

\withbrackets[#1]#2->\normal {#1}{#2}

#1<-1

#2<-2

...

\foo->\@ifnextchar [\withbrackets \withoutbrackets

{\@ifnextchar}

{\@ifnextchar false}

\withoutbrackets#1->\normal {}{#1}

#1<-3

...

Example continued. We show here the use of \@testopt, a LaTeX command that can give a default value to an optional argument. It makes the \withoutbrackets command useless.

\def\@testopt#1#2{%

\@ifnextchar[{#1}{#1[{#2}]}}

\def\foo{\@testopt{\withbrackets}{25}}

\foo[1]{2}\foo34

\foo->\@testopt {\withbrackets }{25}

\@testopt#1#2->\@ifnextchar [{#1}{#1[{#2}]}

#1<-\withbrackets

#2<-25

{\@ifnextchar}

{\@ifnextchar true}

\withbrackets[#1]#2->\normal {#1}{#2}

#1<-1

#2<-2

...

foo->\@testopt {\withbrackets }{25}

\@testopt#1#2->\@ifnextchar [{#1}{#1[{#2}]}

#1<-\withbrackets

#2<-25

{\@ifnextchar}

{\@ifnextchar false}

\withbrackets[#1]#2->\normal {#1}{#2}

#1<-25

#2<-3

...

This example demonstrates \@ifnextcharacter. The command \testa shown here is a copy of \XKV@testopta from the xkeyval package. It takes a token list as argument, reads two optional flags (star and plus), sets boolean values accordingly, then executes the code (that may read some arguments).

\def\@ifstar#1{\@ifnextcharacter*{\@firstoftwo{#1}}}

\def\@ifplus#1{\@ifnextcharacter+{\@firstoftwo{#1}}}

\newif\ifseenplus\newif\ifseenstar

\def\testa#1{\@ifstar{\seenstartrue\testb{#1}}{\seenstarfalse\testb{#1}}}

\def\testb#1{\@ifplus{\seenplustrue#1}{\seenplusfalse#1}}

\def\test{\testa{\testaux}}

\def\testaux#1{\edef\foo{\ifseenstar*\fi\ifseenplus+\fi#1}}

\def\resA{12}

\def\resB{*+12}

\test{12} \ifx\foo\resA\else \bad\fi

\test*+{12} \ifx\foo\resB\else \bad\fi

\catcode`*=3 \catcode`+=3 %Try with different category code

\test *+{12} \ifx\foo\resB\else \bad\fi

\catcode`*=13 \catcode`+=13 %Try with active characters

\test *+{12} \ifx\foo\resB\else \bad\fi

The \ifnum command is used to compare two integers. For instance \ifnum 0<1 evaluates to true, \ifnum 0=1 \ifnum 0>1 evaluates to false. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false. The numbers are read by scanint (scanning a number may involve macro-expansion, hence evaluation of conditionals). The first number must be followed by optional spaces and a character (of \catcode 12) chosen among <, =, >. Examples.

\ifnum 0<1 \else\BUG\fi

\ifnum 0=1 \BUG\fi

\ifnum 0>1 \BUG\fi

\ifnum -3<-2 \else \BUG\fi

\ifnum -3=-2 \BUG\fi

\ifnum -3>-2 \BUG\fi

\def\equalsign{=}% nested conditionals

\ifnum 1\ifnum2<3 4\else6\fi\equalsign 14 \else \BUG \fi

\ifnum 1\ifnum2>3 4\else6 \fi\equalsign 14 \BUG \fi

\ifnum 1\ifnum2>3 4\else6\fi\equalsign 14 \BUG \fi

This is the transcript file for the last line. The difference between the case \else6 \fi and \else6\fi is that the value of the first number is known because of the space (first case) and equals sign (second case).

[3563] \ifnum 1\ifnum2>3 4\else6\fi\equalsign 14 \BUG \fi +\ifnum3570 +\ifnum3571 +scanint for \ifnum->2 +scanint for \ifnum->3 +iftest3571 false +\else3571 +\fi3571 \equalsign->= +scanint for \ifnum->16 +scanint for \ifnum->14 +iftest3570 false +\fi3570

The \ifodd command is used to check whether a number is odd or even. For instance \ifodd12345 evaluates to true. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false. The number is read by scanint (scanning a number may involve macro-expansion, hence evaluation of conditionals). Examples.

\ifodd 1 \else \BUG\fi \ifodd -1 \else \BUG\fi \ifodd 0 \BUG\fi \ifodd 2 \BUG\fi \ifodd -2 \BUG\fi \ifodd 1\ifnum2<3 5 \else6 \fi \else \BUG \fi \ifodd 1\ifnum2>3 5 \else6 \fi \BUG\fi \ifnum 4\ifodd1 2 \else 3\fi=42\else \BUG\fi

You can say \@ifstar{yes-code}{no-code}. The result depends on the character that follows (spaces are ignored). If the character is a star, it is read, and yes-code is executed. Otherwise the next character (or token) is left unchanged, and no-code is executed. This command is defined in LaTeX as \def\@ifstar#1{\@ifnextchar *{\@firstoftwo{#1}}}; it is builtin in Tralics.

In the example that follows, we use the \newif command for setting a boolean. The code should not signal an error. The token that follows \test is not expanded. In the second case, this token is \ifok, hence not a star. In the last two lines, the \expandafter has as effect to replace the \space by a space character, so that this shows that spaces are effectively ignored by \@ifstar.

\newif\ifok

\def\test{\@ifstar\oktrue\okfalse}

\test*\ifok\else\typeout{bug in ifstar1}\error\fi

\test\ifok\typeout{bug in ifstar2}\error\fi

\expandafter\test\space*\ifok\else\typeout{bug in ifstar3}\error\fi

\expandafter\test\space\ifok\typeout{bug in ifstar4}\error\fi

Scratch condition. This is often set by LaTeX to check if some element is in a list (note however that the \in@ command that checks if a list is a sublist of another one uses a different conditional, namely ifin@).

This defines essentially the \ifthenelse command.

If you say \ifthenelse{1<2}{right}{wrong}, the result should be `right'. More generally, the command takes an argument, evaluates it as a boolean, and then reads two arguments and ignores one of them: if the test is true, the third argument is ignored, if the test is false, the second argument is ignored. (said otherwise, evaluating the test might change catcodes, and arguments 2 and 3 are read only after the test is complete).

Evaluation of the boolean value is similar to that of LaTeX. But some details differ, for efficiency reasons.

If you're not sure exactly what equals what, try some experiments.

The command \whiledo uses \ifthenelse for its end test. Some examples are given here

We show here some use of \boolean, \or and \and.

\newboolean{cA}\newboolean{cB}\newboolean{cC}\newboolean{cD}

\def\Test{ %

\ifthenelse{\( \boolean{cA} \and \boolean{cB} \) \or \( \boolean{cC} \and

\boolean{cD} \)}{0}{1}}

\def\testa{\setboolean{cA}{true}\Test \setboolean{cA}{false}\Test}

\def\testb{\setboolean{cB}{true}\testa \setboolean{cB}{false}\testa}

\def\testc{\setboolean{cC}{true}\testb \setboolean{cC}{false}\testb}

\def\testd{\setboolean{cD}{true}\testc \setboolean{cD}{false}\testc}

\testd}

Translation

0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1

Extract of the transcript file indicating the first and last call to \Test

\testa->\setboolean {cA}{true}\Test \setboolean {cA}{false}\Test

{\setboolean}

{setboolean}

{setboolean->\cAtrue}

\cAtrue->\let \ifcA \iftrue

{\let}

{\let \ifcA \iftrue}

\Test-> \ifthenelse {\( \boolean {cA} \and \boolean {cB} \) \or \( \boolean {cC} \and \boolean {cD} \)}{0}{1}

{\ifthenelse}

{ifthenelse \(}

{ifthenelse \boolean}

{boolean}

{boolean->\ifcA}

{ifthenelse \and continuing}

{ifthenelse \boolean}

{boolean}

{boolean->\ifcB}

{ifthenelse -> true}

{ifthenelse \or skipping}

{ifthenelse -> true}

...

\Test-> \ifthenelse {\( \boolean {cA} \and \boolean {cB} \) \or \( \boolean {cC} \and \boolean {cD} \)}{0}{1}

{\ifthenelse}

{ifthenelse \(}

{ifthenelse \boolean}

{boolean}

{boolean->\ifcA}

{ifthenelse \and skipping}

{ifthenelse \or continuing}

{ifthenelse \(}

{ifthenelse \boolean}

{boolean}

{boolean->\ifcC}

{ifthenelse \and skipping}

{ifthenelse -> false}

We give here some examples of \isundefined. The last two lines may fail in standard LaTeX.

\ifthenelse{\isundefined{\or}}{\bad}{ok}

\ifthenelse{\isundefined{\xor}}{ok}{\bad}

\ifthenelse{\isundefined{}}{\bad}{ok}

\ifthenelse{\isundefined{\relax \and \undef}}{\bad}{ok}

Example with \isodd and \equal. In standard LaTeX, the \value command is temporarily redefined so that \cmdB expands to a constant (it is a reference to a counter, so that you can say \the\cmdB or \cmdB=14; in Tralics the last test is false).

\newcounter{FOO} \setcounter{FOO}{1}

\def\cmdA{1}\def\cmdB{\value{FOO}}

\ifthenelse{\isodd{\value{FOO}}}{aa}{bb}

\ifthenelse{\equal{\cmdA}{\cmdB}}{aa}{bb}

The \iftrue command is a test that is always true. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false. See the TeXbook chapter 20 for usefulness of such a command.

You can say \@ifundefined{some-cmd-name}{undef-code}{def-code}. In this case, the character string `some-cmd-name' (the first argument of the command) is converted to a command name, using \csname; all commands in this string are expanded; if the resulting command is undefined, \relax will be used instead; see \csname for details. If the result is undefined (in reality \relax) then the second argument is executed, otherwise the third one is executed.

In the example that follows, we show how the \setcounter command is implemented in LaTeX. Note that \csname is called twice: once to check if the command is defined, and, in that case, again to executed it.

\newcounter{foo}

\def\OO{oo}

\setcounter{f\OO}{17}

\def\setcounter#1#2{%

\@ifundefined{c@#1}%

{\@nocounterr{#1}}%

{\global\csname c@#1\endcsname#2\relax}}

\setcounter{f\OO}{18}

This is the trace of Tralics. You can see that, by default, Tralics does not call \@ifundefined, it checks however that the command is associated to a counter register: in the case of \newdimen\c@foo\setcounter{foo}3, Tralics generates the right error message.

[1618] \setcounter{f\OO}{17}

\OO->oo

\setcounter->\global \c@foo 17\relax

{\global}

{\global\c@foo}

+scanint for \c@foo->17

{\relax}

...

\setcounter#1#2->\@ifundefined {c@#1}{\@nocounterr {#1}}{\global \csname c@#1\endcsname #2\relax }

#1<-f\OO

#2<-18

{\csname}

\OO->oo

{\csname->\c@foo}

{\@ifundefinedfalse}

{\global}

{\csname}

\OO->oo

{\csname->\c@foo}

{\global\c@foo}

+scanint for \c@foo->18

{\relax}

The command \ifvbox is a conditional; it reads a box number N, the test is true if the box contains a vbox. In Tralics, N should be a number between 0 and 1023. The test is always false (because box registers contain XML elements, that are neither hbox nor vbox). See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false.

This tests if the current mode is vertical mode. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false. The internal state of TeX is given by an integer between -3 and +3, they represent horizontal mode, (restricted horizontal mode), vertical mode (internal vertical mode) or display math mode (nondisplay math mode). There are three tests \ifvmode, \ihhmode and \ifmmode. Internal vertical mode, restricted horizontal mode and nondisplay math mode are called `inner', you can test then with \ifinner. When you say \write\chan{\foo}, the token list \foo is evaluated when the current pages is shipped out, and TeX is in no-mode. Example.

\ifvmode 1 \else 2 \fi \ifinner 3\fi

\vbox{\ifvmode 1 \else 2 \fi \ifinner 3\fi}

\ifhmode 1 \else 2 \fi \ifinner 3\fi

\hbox{\ifhmode 1 \else 2 \fi \ifinner 3\fi}

\ifmmode 1 \else 2 \fi $\ifmmode 1 \else 2 \fi$

$$\ifmmode 1 \else 2 \fi\ifinner 3\fi$$

In the current implementation of Tralics, there is no difference between \hbox, \vbox and \xbox{}. As a result, conditionals like \ifvmode may give random results. The test \ifinner is always false outside math mode (it should give the correct answer otherwise). The test \ifmmode gives mostly the right answer.

The command \ifvoid is a conditional; it reads a box number N, the test is true if the box is void. In Tralics, N should be a number between 0 and 1023. In the case \setbox0=\xbox{foo}{}, the box contains an empty element but is not void. The constructions \xbox{}{} and \hbox{} produce a void box. After an assignment of the form \setbox1\box0, the box0 is empty. See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false.

The \ifx command is used to compare two tokens. In a case like \ifx\foo\bar, tokens \foo and \bar are not expanded, the result is true if either the two tokens are not macros, and they both represent the same sequence (character code, category code) pair, or the same \font or \chardef or \countdef\ etc, or the same primitive. In the case where the tokens are macros (user defined), they compare equal if they have the same status with respect to \long and \outer (this was ignored by earlier versions of Tralics) and have the same code (argument list and body). See \if... for what happens in the case where the test is true or false.

\chardef\xx=48 \chardef\yy=`0

\ifx 01 \BUG \fi

\ifx aa \else \BUG \fi

\ifx {} \BUG \fi

\ifx\xx\yy \else \BUG \fi

\countdef\xx17 \countdef\yy 17

\ifx\xx\yy \else \BUG \fi

% \if and \ifx give different results

\ifx\par\relax \BUG\fi \if\par\relax \else \BUG\fi

\let\endgraf\par

\ifx\endgraf\relax \BUG\fi

\ifx\endgraf\par \else \BUG\fi

% The example of the texbook

\def\Xa{\Xc}\def\Xb{\Xd} \def\Xc{\Xe}\def\Xd{\Xe}

\def\Xe{a}

\ifx\Xa\Xb \BUG \fi \ifx\Xb\Xa \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xa\Xc \BUG \fi \ifx\Xc\Xa \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xa\Xd \BUG \fi \ifx\Xd\Xa \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xa\Xe \BUG \fi \ifx\Xe\Xa \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xb\Xc \BUG \fi \ifx\Xc\Xb \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xb\Xd \BUG \fi \ifx\Xd\Xb \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xb\Xe \BUG \fi \ifx\Xe\Xb \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xc\Xd \else\BUG \fi \ifx\Xd\Xc \else \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xc\Xe \BUG \fi \ifx\Xe\Xc \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xd\Xe \BUG \fi \ifx\Xe\Xd \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xa\Xa \else \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xb\Xb \else \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xc\Xc \else \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xd\Xd \else \BUG \fi

\ifx\Xe\Xe \else \BUG \fi

% the expansion of \csname is never undefined

\expandafter\ifx\csname undefined \endcsname\relax \else \BUG \fi

% undefined command do not cause errors

\ifx \undeffined\Undefined \else \BUG \fi

If you say \edef\fooA{\ifnum0=0\fi} and \def\fooB{\relax}, these two commands contain two different tokens that print the same and have the same meaning. Example:

\edef\fooA{\ifnum0=0\fi}

\show\fooA

\fooA=macro: ->\relax .

\def\fooB{\relax}

\show\fooB

\fooB=macro: ->\relax .

\ifx\fooA\fooB \else\typeout{different}\fi

different

\edef\test{\noexpand\ifx\fooA\fooB \typeout{same}\noexpand\fi}

\show\test

\test=macro: ->\ifx \relax \relax \typeout {same}\fi .

\test

same

The \ignorespaces command expands the next token, and removes it, as long as it is a space token. For instance, in a\ignorespaces\space \space b, there are two spaces after the \space command, these are ignored by the reader. On the other hand, the \space command expands to a space, and this one is ignored. Thus, the translation is the same as that of ab.

In the case of a\ignorespaces{ } \space b, there are two spaces not removed by the reader: the spaces after the opening and closing braces. Since the token that follows the \ignorespaces is the brace (unexpandable), nothing happens, and the translation will contain three spaces between the two letters a and b. Note: in general, three spaces in the XML result cannot be distinguished from a single one.

These are mathonly commands, producing double, triple and quadruple integerals. See \xiint for an alternate command. Translation is a sequence of integral signs, with some negative space between them.

The \ij command produces the ij ligature (Unicode U+133, ij). For details see the extended latin characters.

The \IJ command produces the capital IJ ligature (Unicode U+132, IJ). For details see the extended latin characters.

The \Im command is valid only in math mode. It generates a miscellaneous symbol: <mi>ℑ</mi> (Unicode U+2111, ℑ). See description of the \ldots command.

The content of the environment is ignored.

The \ImaginaryI command is valid only in math mode. It generates a miscellaneous symbol: <mi>ⅈ</mi> (Unicode U+2148, ⅈ).

The \imath command is valid only in math mode. It generates a miscellaneous symbol: <mo>ı</mo> (Unicode U+131, ı). See description of the \ldots command.

The \implies command is valid only in math mode. It generates <mo>⇒</mo> (Unicode U+21D2, ⇒).

The \immediate command is a prefix for \openout, \write, or \closeout; it is ignored otherwise. Without the prefix, the command is executed when the box containing the command is shipped out. Since \shipout is not implemented in Tralics, the three commands are always executed immediately, so that \immediate does nothing.

The \in command is valid only in math mode. It generates a relation symbol: <mo>∈</mo> (Unicode U+2208, ∈). See description of the \le command.

After evaluation of \in@{L1}{L2}, the conditional \ifin@ is true if the first argument L1 is a subsequence of the second argument L2., false otherwise. The command could be defined as follows, except that \FOO and \BAR are replaced by special tokens that cannot appear in normal text.

\newif\ifin@

\def\in@#1#2{%

\def\in@@##1#1##2##3\BAR{%

\ifx\FOO##2\in@false\else\in@true\fi}%

\in@@#2#1\FOO\BAR}

Currently, there is no difference between \include{file} and \Input{file}. See \input for details.

Since \include inputs its argument unconditionally, a call of the form \includeonly{file1,file2} is ignored.

The \includegraphics command takes an optional argument and a required argument. The result is a <figure> element. There are some commands or environments that behave differently if the argument or content is a graphic file. Instead of \includegraphics[xx]{yy}, you can say \psfig{xx,file=yy}.

Before version 2.13, Tralics made no difference between an image named foo.ps and one named foo.pdf, the idea being that, if the XML is to be converted to HTML, the images have to be converted also; hence the extension has to be removed in any case. An error is signaled if the file is named foo.bar.gee or something like that. Since version 2.13.3 you will see Error: Wrong dots in graphic file foo.bar.gee. This is because Tralics calls the macro \@filedoterr with the file name as argument. If such files are legal, it suffices to redefine to macro as \@gobble. Example.

\framebox{\includegraphics{x.ps}}

\fbox{\includegraphics{x.pdf}}

\includegraphics[scale=0.3]{x.gif}

\scalebox{0.3}{\includegraphics[scale=0.6]{x.png}}

\scalebox{0.3}{\includegraphics{./x.ps}}

\includegraphics[angle=90]{x}

\rotatebox{30}{\includegraphics{x}}

The translation is:

<figure framed='true' file='x' extension='ps'/> <figure framed='true' file='x' extension='pdf'/> <figure scale='0.3' file='x' extension='gif'/> <figure scale='0.3' file='x' extension='png'/> <figure scale='0.3' file='./x' extension='ps'/> <figure angle='90' file='x'/> <pic-rotatebox angle='30'><figure file='x'/></pic-rotatebox>

The optional argument is a list of assignments. Since version 2.13.4, all options defined by the standard graphicx package are recognized. Moreover, keys can be preset via the \setkeys construct. The name can be clip, keepaspectratio, draft, hiresbb; this is a boolean value, anything but false means true (in particular if no value is given). The name can be type, read, angle, command, origin, ext, scale, case where any value is accepted. The name can be angle. In this case, nothing is done if the value is zero.

The name can be natwidth, natheight, bbllx, bblly, bburx, bbury, bbury, case where the value should a number with an optional dimension (default is bp), it can be bb, viewport, trim, case where the value should a list of four number with an optional dimension (default is bp), separated by space.

The name can by width, height, totalheight, case where a dimension is read (as the example shows, if the calc package is loaded, you can use features of this package).

The name can be file or figure (but you give only one file name, this is the required argument of \includegraphics, so that this applies only to \psfig). As the example below shows, you can add special characters like an underscore in the file name.

Example.

\def\myscale{.3}

\includegraphics[height=15cm,width=\columnwidth]{A}

\includegraphics[totalheight=18cm,width=\textheight-2cm]{AA}

\includegraphics[height=\textwidth,width=.1\linewidth]{../../a_b:c}

\includegraphics[bb=10 20 30 40,clip=true,keepaspectratio=true,%

draft=true,hiresbb=true,origin=c]{D}

\includegraphics[bb=10pt 20pt 30pt 40pt,clip=true,keepaspectratio=true,%

draft=true]{D}

\includegraphics[bbllx= 9.9626,bblly= 20pt,bburx= 30,bbury=40,clip=false,%

keepaspectratio=false,draft=false,type=aa,ext=bb,read=cc,command=dd,%

hiresbb=false]{E}

\includegraphics[natwidth= 3,natheight=40,clip=,hiresbb,keepaspectratio=,%

scale=\myscale,draft=]{F.ps}

{\setkeys{Gin}{width=20pt}\includegraphics{G}}

The translation is

<figure rend='inline' width='427.0pt' height='426.79134pt' file='A'/> <figure rend='inline' width='513.0945pt' totalwidth='512.1496pt' file='AA'/> <figure rend='inline' width='42.7026pt' height='427.0pt' file='../../a_b:c'/> <figure rend='inline' origin='c' hiresbb='true' draft='true' keepaspectratio='true' clip='true' bb='10.03749pt 20.075pt 30.11249pt 40.15pt' file='D'/> <figure rend='inline' draft='true' keepaspectratio='true' clip='true' bb='10.0pt 20.0pt 30.0pt 40.0pt' file='D'/> <figure rend='inline' hiresbb='false' command='dd' read='cc' ext='bb' type='aa' draft='false' keepaspectratio='false' clip='false' bbury='40.15pt' bburx='30.11249pt' bblly='20.0pt' bbllx='9.99995pt' file='E'/> <figure rend='inline' draft='true' scale='.3' keepaspectratio='true' hiresbb='true' clip='true' natheight='40.15pt' natwidth='3.01125pt' file='F' extension='ps'/> <figure rend='inline' width='20.0pt' file='G'/></p>

The names are not hard-coded. If the configuration file contains

att_scale = "Scale" att_file = "File" att_file_extension = "Extension" att_angle = "Angle" att_width = "Width" att_height = "Height" att_clip = "Clip" xml_figure_name = "Figure"

then the translation may be

<Figure Height='6.cm' Width='7.5cm' Angle='20' Clip='true' Scale='2' File='Logo' Extension='ps'/>

If you compile the file foo, then Tralics will generate a file named foo.img that contains the following.

# images info, 1=ps, 2=eps, 4=epsi, 8=epsf, 16=pdf, 32=png, 64=gif

see_image("Logo",1+16,3);

see_image("../../a_b:c",0,1);

see_image("x_",0,1);

see_image("x",0,6);

This has to be interpreted as follows: the logo was included 3 times, it exists with extension `ps' and `pdf', the other images were not found (extensions ps, eps, epsi, epsf, pdf, png and gif were tried). Image x was included six times. Note the following trick: if the image is ./x.ps, you will see x in the img file; since version 2.13.2, you will see file='./x' extension='ps' in the XML file.

The \indent command creates an indented paragraph. See description of the \noindent command.

You can say \index{A!B!C}, this produces a subsub item in a subitem of an item in the index. Each of A, B, C can be of the form foo, foo@bar, foo|gee, or foo@bar|gee. There are four special characters (exclamation point, at-sign, vertical bar, and double quote; there meaning is normal when preceded by a double quote. Tralics fully expands everything (if you use LaTeX and makeindex, there is a possibility to delay expansion after processing by makeindex; the situation is simpler in Tralics. A non-obvious point is to put a hat in the index at the right position.

In the case of foo@bar|gee, the index will contain 'bar', and makeindex will apply the command \gee to the page of the reference. The Tralics translation is a <index> element, with a target attribute, whose value is the list of the IDs of the anchors. We could add an attribute encap, with as value the list of all these 'gee'; this is not yet done, and the page encapsulation is silently discarded. The string 'foo' will be used as sort key. In the case of xfoo@bar and yfoo@bar, we consider this as the same entry, with different keys; makeindex may disagree. Example

OK

\index{verb}a

\index{vérb}b

\index{verb@verb}c

\index{vérb@verb}d

\index{vérb@vérb}e

\index{vérb@vérb|bf}f

\index{vérb!vèrb}g

\index{vérb!vèrb}h

OK

The translation may be the following, some further explanations will be given below.

<p>OK <anchor id='uid1'/>a <anchor id='uid2'/>b <anchor id='uid3'/>c <anchor id='uid4'/>d <anchor id='uid5'/>e <anchor id='uid6'/>f <anchor id='uid7'/>g <anchor id='uid8'/>h OK</p> <theindex><index target='uid1 uid3 uid4' level='1'>verb</index> <index target='uid2 uid5 uid6' level='1'>vérb</index> <index target='uid7 uid8' level='2'>vèrb</index> </theindex>

Tralics implements some features of the index package. The command \newindex takes an optional argument A, an optional star, a unique tag B, two arguments C, D and a last argument E. You should refer to the documentation of the package for explanations of A, C, D, and the star. It calls \@newindex with arguments B and E. The main index has tag default, the glossary has tag glossary, with titles Index and Glossary. Nothing happens if you try to redefine an existing index; the main index will be used if you try to use an undeclared index. In the example below, we define two indexes, A and B, but use only A.

The \index command takes an optional star (ignored) and an optional argument, which is the tag of an index. There is no difference between \glossary{foo} and \index[glossary]{foo}; In the same fashion \index{foo} is the same as \index[default]{foo}. The command \addattributetoindex takes three arguments (the first one being optional, and specifying an index). It adds an attribute pair to the index. The title attribute of an index is the title described above (Index for the main index), but you can overwrite it using this command. For instance, we redefine the title of the glossary an the main index.

The commands \makeindex and \makeglossary have no effect. The commands \printindex and \printglossary can be used to say where the index is to be put. By default the end of the document is considered, and the glossary is put after all other indexes. Example.

\newindex{A}{}{}{Second Index}

\newindex{B}{}{}{Third index}

\addattributetoindex{title}{First Index}

\addattributetoindex[A]{head}{Second Index}

\addattributetoindex[glossary]{title}{A Glossary}

These words are in the glossary

\glossary{G1}1\glossary{G2}2

\glossary{G1}3\index[glossary]{G2}4

These are in the second index

\index[A]{G1}1\index[A]{G2}2

\index[A]{G1}3\index[A]{G2!G3}4

Translation

<theindex head='Second Index' title='Second Index'> <index target='uid24 uid26' level='1'>G1</index> <index target='uid25' level='1'>G2</index> <index target='uid27' level='2'>G3</index> </theindex> <theglossary title='A glossary'> <index target='uid20 uid22' level='1'>G1</index> <index target='uid21 uid23' level='1'>G2</index> </theglossary>

Penalty used used a linebreak occurs between two footnotes; unused by Tralics.

Penalty used used a linebreak occurs between two lines in an equation; unused by Tralics.

The \inf command is valid only in math mode. Its translation is a math operator of the same name: <mo form='prefix' movablelimits='true'>inf</mo>. For an example see the \log command.

The \infty command is valid only in math mode. It generates a miscellaneous symbol: <mi>&infty;</mi> (Unicode U+221E, ∞). See description of the \ldots command.

The \injlim command is valid only in math mode. Its translation is a math operator of the same name <mo form='prefix' movablelimits='true>inj lim</mo>. For an example see the \log command.

The \inplus command is valid only in math mode. It generates <mo>⨭</mo> (Unicode U+2A2D, ⨭).

The \input command takes one argument, a file name, and opens the file, exactly like \InputIfFileExists described below. An error is signaled if the file does not exists.

There is an alternate syntax, without braces. The name of the file is obtained by expanding tokens, and looking for characters. Letters and underscore characters (of catcode 8) are allowed. A space terminates parsing. Other characters terminate also, but they are pushed back, to be read again. You can say for instance: \input taux1.tex\input taux2.tex

You can say \Input{foo} or \include{foo}, the behavior is the same, but the braces are required. You can put a star after the command name, as a side effect, the at-sign @ character becomes a letter while reading the file (and its category code is restored at the end). The same holds for \InputIfFileExists.

Variables that holds input encoding method. There are 34 (maybe more) input

methods. Method 0 is UTF8, method 1 is latin1, these cannot be changed. All

other methods define a translation table. If you say \input@encoding@val

4 5 6, this changes the value for encoding 4 of the character 5 to be

6. The first number must be between 2 and the size of the table; the second

number must be a integer between 0 and 255, the last number should be between

0 and maxchar (less than 2^16). If you say \the\input@encoding@val 4

5 this gives the value of encoding 4, character 5. The two commands

\input@encoding and input@encoding@default are

reference to the current or default encoding. Thus

\input@encoding=3 is a declaration to use encoding 3, and

\theinput@encoding=3 typesets the current encoding.

Each file has its own encoding. The default encoding is used when the file is

opened. A command line parameter lets you select between encoding 0 and 1.

If the file contains, on the first line iso-8859-1

or utf8-encoded

(without the quotes), and somewhere near the beginning %&TEX encoding =

UTF-8

, then utf8 or latin1 is selected. [Note: recommended syntax

is coding: utf-8

].

If your document is encoded in

latin9, then you should use the inputenc package, that defines an encoding

number (for instance 3), defines the encoding, changes the default encoding,

and that of the calling file.

You can use commands like \DeclareOption, this adds an option to the current class or package, and the command has no effect outside a class or package. If you say \InputClass{foo}, Tralics will input the file foo.clt, and the content is considered to be part of the current class file.

The \InputIfFileExists command takes three arguments, say A, B, C. The behavior is like \IfFileExists{A}{B\Input{A}}{C}, see \IfFileExists, for how existence of the file A with possible extension is checked. If you put a star after the command, it will be transmitted to \Input. This will have as a consequence that the character '@' is a letter while reading the content of the file. You can also put a plus sign after the optional star, this means that the file is not searched in the input directory stack.

The procedure is a bit optimized: first all arguments are read; then the existence of the file is checked. If the file does exist, it is opened; this has as consequence that all unread characters on the current line are saved on a special stack, they will be read again at the end of the current file. Then one of the token lists B or C is inserted into the list of unread tokens. If the star form is used, the category code of the at-sign character is changed, its old value is saved on the special stack mentioned above.

Let's assume that no file named nohope exists, but the file taux2.tex contains the following lines.

% aux file for testing tralics

% this file contains nothing useful

\mytypeout{in file taux2.tex}

\endinput

The file should finish with a \endinput, but not on the last line.

It is possible to generate this file using the following code

\begin{filecontents}{taux2.tex}

% aux file for testing tralics

% this file contains nothing useful

\mytypeout{in file taux2.tex}

\endinput

The file should finish with a \endinput, but not on the last line.

\end{filecontents}

The following piece of code defines macros \foo, \bad, etc, in such a way that \bad provokes an error, unless \mytypeout is called twice, with a \foo between the two calls. Thus, the piece of code checks that the file is loaded twice.

\def\bad{\errmessage{BAD}}\let\ybad\bad

\def\mytypeout#1{\def\bad{\xbad}}

\def\foo{\ifx\bad\ybad\else\let\xbad\relax\fi\let\bad\ybad}

\def\IIFE#1{\InputIfFileExists{#1}{}{}}

\IIFE{taux2}\IIFE{nohope}\foo\IIFE{taux2}

\bad

You can say \inputlineno=37, this attempts to put the integer 37 in a read-only variable. (See scanint for details of argument scanning). The variable contains the current input line number.

You can say something like \insert200 \relax{\bf a}. What happens is explained at the end of Chapter 15 of the TeXbook, see here for details). Essentially, this is used to implement footnotes, hence depends on how TeX makes pages from lines of input. Thus, this command is not implemented in Tralics. However, if you say \insert2000 \bf, you will get three errors: a first that says that \insert is unimplemented, a second that says that the number is out of range and a third that says that an opening brace was missing (but no brace is inserted).

This command defines a location in the XML tree where Tralics will insert the bibliography. For details see section 2.8 Bibliography of the raweb documentation.

When TeX computes the cost of a pagebreak, it takes the sum of the penalty of the current breakpoint and \insertpenalties. This is the accumulated penalty for split insertions.

The number of insertions not handled is in \insertpenalties while an \output routine is active.

In Tralics, you can assign any value to \insertpenalties, nothing happens. You can consult the value, you will always see zero.

The \int command is valid only in math mode. Its translation is a variable-sized symbol: <mo>∫</mo> (Unicode U+222B, ∫). For an example see the \sum command.

You can say \interactionmode=37, this is an extension defined by ε-TeX. (See scanint for details of argument scanning). The \interactionmode command allows you to get or set the current interaction mode, an integer between 0 and 3. Setting it is no-op in Tralics (no error signaled), the value is always zero (this is batchmode in TeX, which is more or less the only mode of interaction of Tralics).

The \intercal command is valid only in math mode. Its translation is <mo>⊺</mo> (Unicode U+22BA, ⊺).

The \interleave command is valid only in math mode. Its translation is <mo>⫴</mo> (Unicode U+2AF4, ⫴).

This is an extension defined by ε-TeX. See \widowpenalties for syntax and usage.

When you say \interlinepenalty=95, then TeX will use 95 as penalty for a page break between two lines of text. Unused by Tralics. (See scanint for details of argument scanning).

The expression \intertext{foo} is the same as \multicolumn{2}{l}{\mbox{foo}}\\. This must be used inside a table or array, for instance the align environment. Typical use is LaTeX companion example 8-2-21.

There are a great number of parameters used by LaTeX to control float placement; they are all unused by Tralics. There are five rubber length parameters, \intextsep controls the space between a float and the texts in the non-floating case, \floatsep controls the space between two floats, \textfloatsep controls the space between a float and surrounding text, \dblfloatsep and \dbltextfloatsep are analogous quantities for floats that span more than one column. There are four counters, topnumber (maximal number of floats on top of a page), bottomnumber (maximal number of floats on bottom of a page), dbltopnumber (maximal number of multicolumn floats on top of a page), and totalnumber (maximal number of floats on a page). There are six real numbers, \topfraction, \bottomfraction, \textfraction, \floatpagefraction, \dbltopfraction and \dblfloatpagefraction. If \topfraction is 0.75, this means that a page formed of floats (on the top) followed by text cannot contain more than 75% of floats. Same for \bottomfraction and \dblfloatpagefraction. Other parameters define the minimum quantity of text or float that can appear on a page.

The \InvisibleComma command is valid only in math mode. It generates the invisible operator <mo>⁣</mo> (Unicode U+2063, ).

The \InvisibleTimes command is valid only in math mode. It generates the invisible operator <mo>⁢</mo> (Unicode U+2062, ).

The \iota command is valid only in math mode. It generates a Greek letter: <mi>ι</mi> (Unicode U+3B9, ι). See description of the \alpha command.

You can say \isodd{25} in order to check that 25 is an odd number inside \ifthenelse. You could also use \ifodd 25 ...\fi. See \ifthenelse for details.

The standard way to check that a command is undefined is to compare it (with \ifx) to an undefined command (and hope that nobody has defined it). Inside \ifthenelse, you can say \isundefined{\foo}, and the effect is the same, see \ifthenelse for details. You can also say \@ifundefind{foo}{...}{...} (see \@ifundefined)

The \it command is equivalent to \normalfont\itshape. In other words, it selects a font of roman family, medium series and italic shape. For an example of fonts, see \rm.

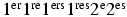

The \item command creates an item in a list. It takes an optional argument, that is the label of the item, which is evaluated inside a group. See also \@item and \@itemlabel. Here is an example of three types of lists.

\begin{itemize}

\item[first item] This is the first item

\item[\it second item] This is the second item

\item[third] This is the last item

\begin{description}

\item[a] description of a.

\item[b] description of b.

\item[cde] description of cde.

\item[defgh etc] description of other letters

\begin{enumerate}

\item One

\item Two

\item Threee

\end{enumerate}

\end{description}

\end{itemize}

This is the translation of the example above. Note that each item contains one or more paragraphs, and that each item has a unique id, and a id-text. If the local list counter is enumi, the id-text is the value of \theenumi after incrementing the counter. See enumi for additional explanations (in the example above, three counters are used, Enumi, Enumii and enumi). In the case of a description, the macro \labelenumi (the name depends on the enumeration level) is used to produce the label attribute. Each item with an optional argument has a label. How it is typeset depends on the style sheet (in the preview below, labels in an enumeration are flushed right, except if too big).

<list type='simple'>

<label>first item</label>

<item id-text='1' id='uid1'><p noindent='true'>This is the first item</p></item>

<label><hi rend='it'>second item</hi></label>

<item id-text='2' id='uid2'><p noindent='true'>This is the second item</p></item>

<label>third</label>

<item id-text='3' id='uid3'><p noindent='true'>This is the last item</p>

<list type='description'>

<label>a</label>

<item id-text='3.1' id='uid4'><p noindent='true'>description of a.</p></item>

<label>b</label>

<item id-text='3.2' id='uid5'><p noindent='true'>description of b.</p></item>

<label>cde</label>

<item id-text='3.3' id='uid6'><p noindent='true'>description of cde.</p></item>

<label>defgh etc</label>

<item id-text='3.4' id='uid7'><p noindent='true'>description of other letters</p>

<list type='ordered'>

<item id-text='1' id='uid8' label='(1)'><p noindent='true'>One</p></item>

<item id-text='2' id='uid9' label='(2)'><p noindent='true'>Two</p></item>

<item id-text='3' id='uid10' label='(3)'><p noindent='true'>Threee</p></item>

</list>

</item>

</list>

</item>

</list>

The following image was produced in 2003. You may notice

that the labels of the enumeration are unrelated to the label attributes of the XML

The \item command is normally bound to \@@item but can be changed to \@item, either by using \let in the tex file or alternate_item="true" in the configuration file. The difference lies in the translation of the optional argument

The default rule is: an optional argument to the \item command produces a <label> element, and in a list, you should either use no optional argument, or provide an optional argument for every item. If you change \item to \@item, this gives the following behavior: an optional argument produces a label attribute, and translation of \item is always a single element. This forbids using math formulas in the optional argument (for instance \item[$\bullet$] won't work).

A rule of thumb is: optional arguments are useless for itemize, mandatory for description, and automatic for enumerate. Here automatic means: the labels a, b, c may be computed by Tralics, the XML to HTML converter, or the web browser, or whatever. These labels were not computed by early versions of Tralics. In the current version, in the case of description, the label is computed (unless explicitly given), and produces an attribute (this means that using \fnsymbol for producing the label will produce an error, since it generates math expressions). The command \enumi@hook (its name depends on the enumeration level) is executed (if defined) at the start of the environment. In the example that follows it adds an attribute to the current element (the list). Note that the hook is executed after \@itemlabel has been redefined to \theenumi, it can locally redefine this variable.

\makeatletter

\let\item\@item

\newcounter{Ctr}

\def\enumii@hook{\AddAttToCurrent{list-counter}{Roman}}

\begin{list}{(\theCtr)}{HEY!\usecounter{Ctr}}

\item[a] bla bla

\item ble ble

\item blu blu

\begin{enumerate}

\item e1

\item e2

\def\@itemlabel{[\theenumi]}

\item e3

\item

\begin{enumerate}\def\@itemlabel{[\theenumi,\theenumii]}

\item i1

\item i2

\item[foo] i3

\item i4

\end{enumerate}

\item e5

\end{enumerate}

\item bli bli

\end{list}

Translation

<list type='description'><p>HEY!</p>

<item id-text='1' id='uid11' label='a'><p noindent='true'>bla bla</p>

</item>

<item id-text='2' id='uid12' label='(2)'><p noindent='true'>ble ble</p>

</item>

<item id-text='3' id='uid13' label='(3)'>

<p noindent='true'>blu blu</p>

<list type='ordered'>

<item id-text='1' id='uid14' label='(1)'><p noindent='true'>e1</p>

</item>

<item id-text='2' id='uid15' label='(2)'><p noindent='true'>e2</p>

</item>

<item id-text='3' id='uid16' label='[3]'><p noindent='true'>e3</p>

</item>

<item id-text='4' id='uid17' label='[4]'>

<list list-counter='Roman' type='ordered'>

<item id-text='4a' id='uid18' label='[4,a]'><p noindent='true'>i1</p>

</item>

<item id-text='4b' id='uid19' label='[4,b]'><p noindent='true'>i2</p>

</item>

<item id-text='4c' id='uid20' label='foo'><p noindent='true'>i3</p>

</item>

<item id-text='4d' id='uid21' label='[4,d]'><p noindent='true'>i4</p>

</item>

</list>

</item>

<item id-text='5' id='uid22' label='[5]'><p noindent='true'>e5</p>

</item>

</list>

</item>

<item id-text='4' id='uid23' label='(4)'><p noindent='true'>bli bli</p>

</item>

</list>

The value of this command is set by list environments. In the case of enumeration it is \labelenumXXX (where XXX is the lowercase roman letter value of the list depth). In the case of other standard lists, the value is \relax. In the case of list, it is a macro without arguments that contains the value of the first argument of the environment. The \item command takes an optional argument; if omitted, the value of \@itemlabel is used, provided this is not \relax.

This holds a dimension (indentation of the first line of an item). Not used by Tralics.

This is an environment in which you can put items. See description of \item above.

This holds a length (amount of extra vertical space, in addition to \parsep, inserted between successive list items. Not used by Tralics.

The \itshape command changes the shape of the current font to an italic shape. For an example of fonts, see \rm.

Private commands used by \@whiledim, \@whilenum, and \@whilesw respectively.

The expansion of the \@ixpt is 9.

back to home page

© INRIA 2003-2005, 2006

Last modified $Date: 2015/11/27 17:06:16 $